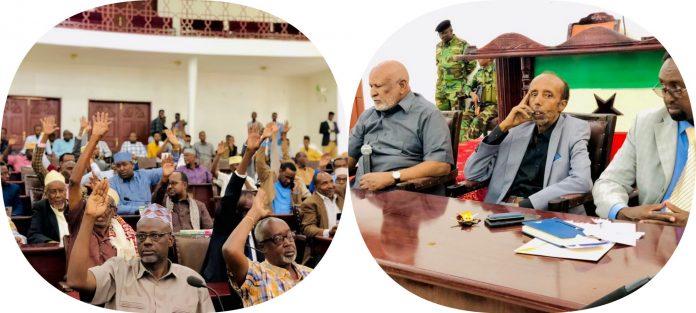

The Upper House – Guurti – of the Republic of Somaliland’s bicameral parliament, Saturday, extended the president’s term in office by over two years concurrently adding theirs to 5 more years.

in a brief statement the House released, it stated that the extended term of the President will end on 13 December 2024 where, presently, it was to expire on the same date this year.

The move, critics believe, throws the budding democracy of Somaliland into an unfathomable abyss.

For one, it comes at a time the Lower House – the House of Representatives (HoR) – is torn asunder into two camps whose differences have grown into a stage where neither is any longer comfortable sitting with the other in the panel hall. No sessions have been held since last Tuesday when a controversial bill on the mode of elections has been passed to the Upper House by opposition MPs. The bill also caused a rift between the leaderships of the two Houses.

Secondly, it closely follows a nine-month extension the Somaliland electoral Commission requested in order to prepare for a presidential election that was to constitutionally have happened on 13 November 2022. The proposal while it was generally welcomed by all three national parties, including the ruling Kulmiye, made the two opposition political parties of UCID and Waddani uncomfortable as they saw in it an opening line for the Guurti to extend the President’s term as it wished and without waiting for a consensus among major political stakeholders.

Thirdly, the extension denies both existing political parties and political associations whose screening had been underway the right to partake in scheduled elections which are now pushed back to a period that would see them hanging in limbo without a constitutional mandate or existence. Political associations can only have a political existence up to circa mid-next year and that is if the registration committee grants them a short extended life.

Political parties, incidentally, never publicly owned up to their role in the presidential and Guurti extensions through a number of puerile-like tantrums that vehemently and acoustically opposed nominations before suddenly – and inexplicably – giving way without further resistance. For instance, Waddani and UCID accused members of the political parties and associations committee and NEC, respectively, of belonging to the ruling party wasting precious time. In both instances, they later approved the very same members they stopped on mid-track.

Fourthly, for opposition political parties the extension calls their bluff. Short of taking up arms – a very unlikely development – there is little they can do but to reach out to the President for a settlement of another kind that may possibly end in a shortened extension period.

And, lastly, the extension the Guurti passed grants the ‘grantor’ an overstay of 24 years. The Guurti, constitutionally were to have been elected every six years once. The sitting House came to office in February 1997. 2027 – the end of the current extended term – will make members – perhaps – the longest sitting, unmandated House in the democratic world.

How stakeholders react to the extension is still in the making with respective storms gathering on the horizon. ![]()