Think of the Sahara Desert. What do you see?

Most of you are probably envisioning a dune sea filled with wave after wave of windswept sand scorched by a relentless sun. The sight seems almost endless – desolation in every direction.

In truth, this description rings true for just a minor proportion of the largest hot desert on Earth. Of the Sahara Desert’s roughly 9 million square kilometers (almost the same size as China), only about a quarter is actually covered in sand. The rest is a hard, rocky, scraggly surface, its mundanity occasionally broken by salt flats, mountains, or valleys.

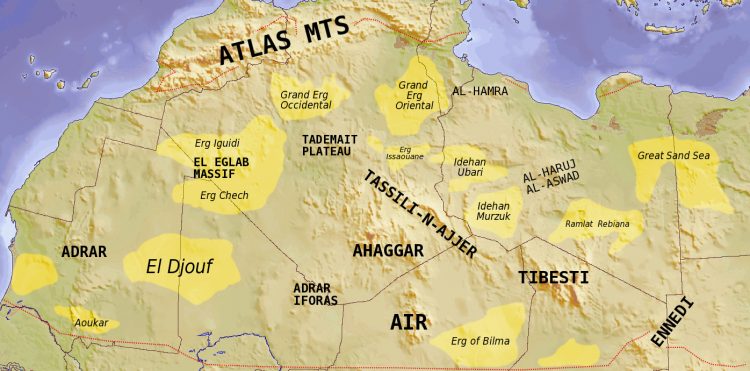

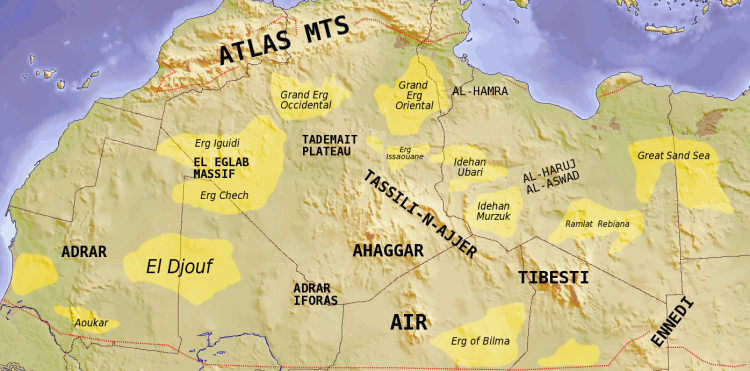

The Sahara’s picturesque dunes are relegated to areas called ergs – broad, flat areas of desert covered in sand. These form downwind of dried out riverbeds, deltas, floodplains, and lakes, where previously drowned sediment desiccates and, over the years, gets blown for miles and miles.

You can see how the Sahara’s ergs conspicuously line up with the locations of long ago bodies of water.

The Great Sand Sea, straddling Egypt and Libya, is one of the Sahara’s most notable ergs. It alone covers 72,000 square kilometers, an area just a tad smaller than the state of South Carolina in the U.S.

The Sahara’s sand dunes stand out aurally as well as visually. Large, curved dunes primarily composed of silica-containing sand grains between 0.1 mm and 0.5 mm in diameter with a certain humidity can generate a tremendous resonating noise when wind passes over them. This roaring hum, likely created by friction between sand grains or air compression, can reach 105 decibels, roughly equivalent to a nearby helicopter!

While it is technically a myth that the Sahara Desert is mostly covered by sand, in a few thousand years, our conception of the Sahara might change entirely (provided we are still around). That’s because the Sahara may alternate from dry and inhospitable to wet and verdant every 20,000 years or so. Examining dust deposits going back 240,000 years, a team of researchers reported in 2019 that sediments seemed to change from dry to wet in sync with slight changes in the tilt of Earth’s axis. Indeed, the Sahara seems to be a region of Earth in geological flux.

By Ross Pomeroy

Real Clear Science