The world was preoccupied with the immediate aftermath of 9/11. But exactly three months later, on 11 December, the World Trade Organization (WTO) was at the centre of an event that was to cast as strong a shadow over the 21st century, changing more people’s lives and livelihoods around the world than the attacks on America.

Yet few know it even happened, let alone its date. China’s admission to the World Trade Organization changed the game for America, Europe and most of Asia, and indeed for any country in possession of industrially valuable resources, such as oil and metals.

It was a largely unnoticed event of epic geopolitical and economic importance. It was the root imbalance behind the global financial crisis. The domestic political backlash against the outsourcing of manufacturing jobs to China has reverberated around the western G7 nations.

The promise, suggested by the likes of former US President Bill Clinton, was that “importing one of democracy’s most cherished values, economic freedom”, would enable the world’s most populous nation to follow the path of political freedom too.

“When individuals have the power not just to dream, but to realise their dreams, they will demand a greater say,” he said.

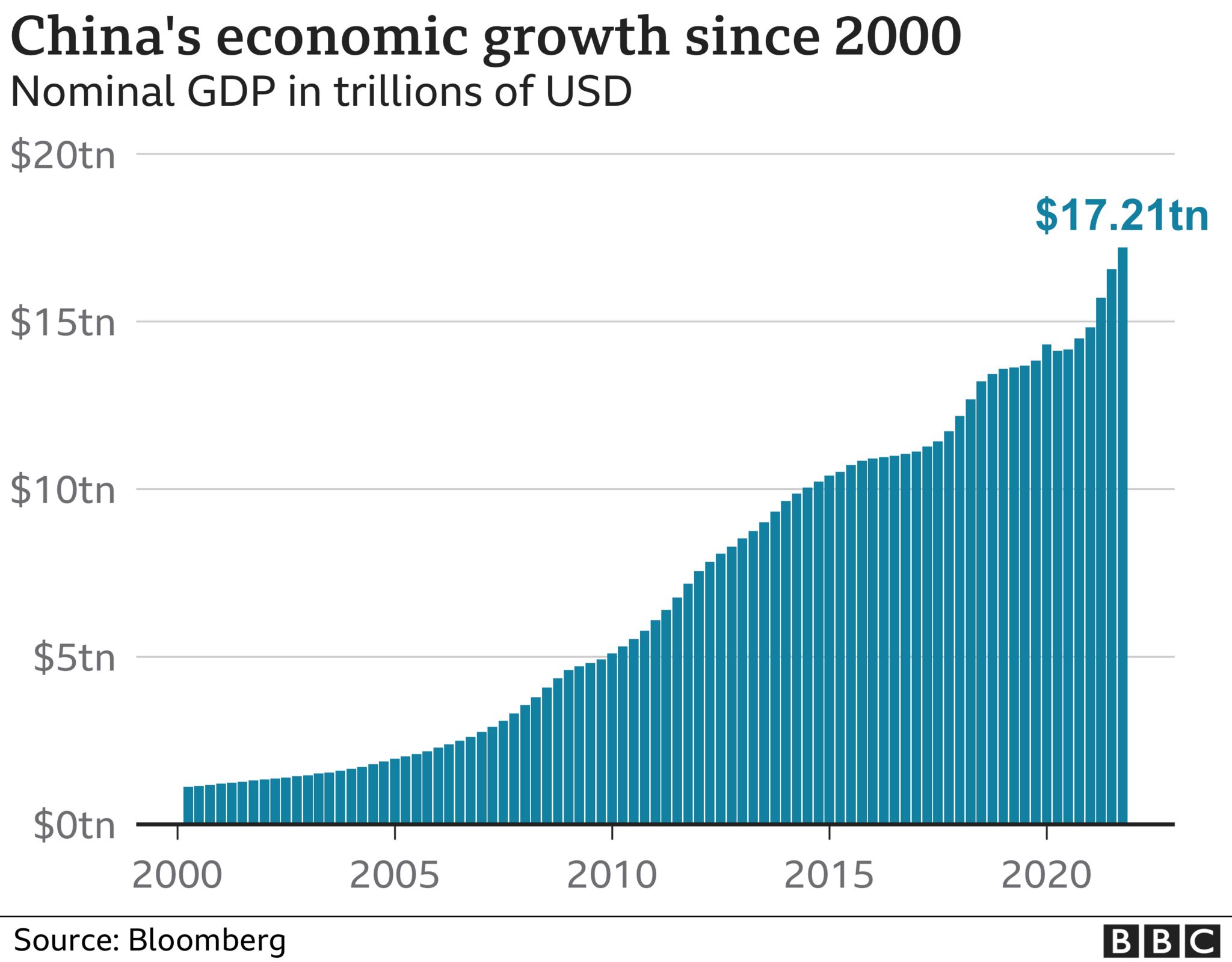

But that strategy failed. China began its ascent to its current status as the world’s second biggest economy – and is on a seemingly inevitable path to becoming the world’s biggest.

Indeed the US trade representative responsible for negotiating China’s WTO deal, Charlene Barshefsky, told a Washington International Trade Association panel this week that China’s economic model “somewhat disproved” the Western view that “you can’t have an innovative society, and political control”

“It’s not to say that China’s innovative capacity is enhanced by its economic model,” she added. “But it is to say that what the West thought were incompatible systems may not be necessarily incompatible systems.”

Former US Trade Representative, Charlene Barshefsky (l) gives her speech watched closely by Boao Secretary General Long Yongtu (R) during a luncheon at the Boao Forum for Asian in Hainan Province, China. IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

Former US Trade Representative, Charlene Barshefsky (l) gives her speech watched closely by Boao Secretary General Long Yongtu (R) during a luncheon at the Boao Forum for Asian in Hainan Province, China. IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESUp until 2000 China’s global economic role had been principally as one of the world’s biggest manufacturers of plastic gubbins and cheap tat. Important, yes, but neither world-beating nor world-changing.

China’s accession to the top table of world trade heralded a massive global transformation. A powerful combination of China’s willing workforce, its super-high-tech factories, and the special relationship between the Chinese government and Western multinational corporations changed the face of the planet.

An army of cheap Chinese labour began to produce the goods that underpin Western living standards, as China seamlessly inserted itself into the supply chains of the world’s biggest companies. Economists call it a “supply shock”, and its impact certainly was shocking. Its effects are still reverberating around the world.

In 2000, China was the seventh-largest goods exporter in the world, but it quickly reached the number one spot. China’s annual growth rate, already at 8%, went stratospheric at the height of the world boom, peaking at 14%, and stabilised at 15% last year.

Container ships are the juggernauts of global trade. In the five years after China joined the WTO, the number of containers on ships coming in and out of China doubled from 40 million to more than 80 million. By 2011, a decade after the country became a WTO member, the number of containers going in and out of China had more than trebled to 129 million.

Last year it was 245 million, and while about half of the containers going into China were empty, nearly all those leaving China were full of exports.

There has also been a massive expansion in China’s highway network, which increased from 4,700km in 1997 to 161,000km by 2020, making it the largest network in the world, connecting 99% of cities with populations of over 200,000.

In addition to its state-of-the-art freight infrastructure, China also needs materials such as metals, minerals and fossil fuels to support its manufacturing boom. One material essential to China’s burgeoning automotive and electrical appliance industries is steel. In 2005 China became, for the first time, a net exporter of steel, and has since become the world’s largest exporter.

Through the 1990s, China’s production of steel hovered at around 100 million tonnes per year. After WTO membership, it exploded to around 700 million tonnes by 2012 and exceeded one billion tonnes in 2020.

China now accounts for 57% of world production and produces significantly more steel on its own than the rest of the globe managed together back in 2001. The same goes for ceramic tiles, and plenty of other ingredients of industry.

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESIn electronics, clothing, toys and furniture, China became the dominant source of supply, forcing down export prices all around the world. Economists noticed a “once-for-all” shock in global prices following China’s WTO entry. China’s clothing exports doubled between 2000 and 2005, and its share of the value of global trade went from one fifth to one third.

After 2005, production quotas in the textile industry were also lifted, leading to an even bigger production shift to China. However, as production in China became more expensive and production has shifted to developing countries such as Bangladesh and Vietnam, this has fallen back to 32% of clothes last year.

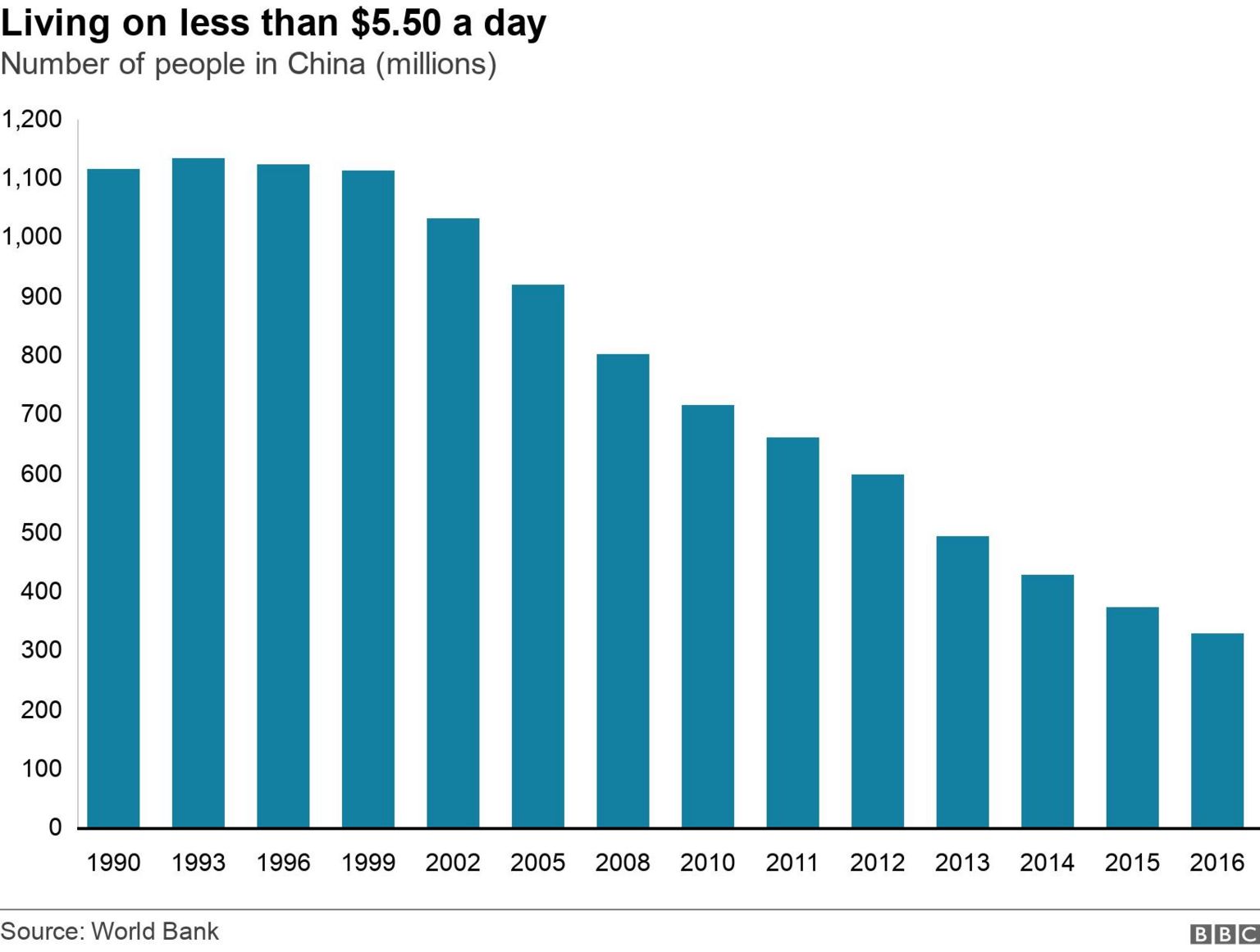

The Chinese minister responsible for WTO accession, Long Yongtu, made an admission reflecting on the past two decades. “I don’t believe China’s WTO accession was a historic job-killing mistake [for the US and the West],” he said. “However I recognise the allocation or the benefit is uneven. The complete picture is that when China got his own development, it also provided the rest of the world with a huge export market.”

But there was a sting in the tail – that it was US politics that failed to account for the inevitable impact of Chinese competition on some sectors. “When the uneven distribution of wealth happens, a government should take measures to adjust that distribution through domestic policies, but it’s not easy to do that,” said Long Yongtu.

“Maybe blaming others much easier, but I don’t think blaming others can help to solve the problem. In China’s absence, the US manufacturing industry would move to Mexico.”

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES Shanghai Yangshan deepwater port

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES Shanghai Yangshan deepwater portHe then relayed an anecdote of a Chinese glass manufacturer who struggled with opening a factory in the USA: “It’s very difficult for him to find competitive workers there. He told me American workers’ bellies are bigger than his,” said the minister.

So right now we have come full circle. China has had significant economic success within the WTO. Right now the Biden administration seems in no hurry to change the obstructive policies of his predecessor there. The trade scepticism is very real. China has used WTO membership to go well beyond its earmarked role as workshop to the West.

It has, for example, strategically planned alliances to get access to significant amounts of the rare earth materials that should power the net zero climate change economic revolution. It has deployed the state behind industrial expansion around the world. The US is looking to contain China diplomatically and economically, and seeking allies in this endeavour in Europe and Asia.

As former US trade representative Barshefsky puts it, China has been “on this very divergent course for some time. What does that mean? A strengthening of a state-centric economic model fuelled by massive subsidisation to designated industries… the re-emergence of China as a great power, and the leader of what it calls the Fourth Industrial Revolution. This is a lot to handle. The WTO can’t handle it.”

So, 20 years on – the world transformed by a little-noticed decision. It’s been a huge success for China. The intended geopolitical strategy of the West failed. Indeed, rather than China becoming more like the West politically, as a result of this decision, the West economically speaking is becoming a bit more like China.

Faisal Islam

Faisal Islam

Economics editor

@faisalislamon Twitter

Source: BBC