SUMMARY

The U.S. should recognize Somaliland as an independent country. In practice, the territory is not now, nor is likely to be, a part of Somalia. Acknowledging that reality would allow Washington to create more effective policy in an important and contested region. A strong relationship with an independent Somaliland would hedge against the U.S. position further deteriorating in Djibouti, which is increasingly under Chinese sway. It would demonstrate the benefits Washington confers on those who embrace representative government and would allow the U.S. to better support the territory’s tenacious, but still-consolidating, democracy. An independent Somaliland would be a stable partner that has little risk of experiencing the tumult that frustrates American interests elsewhere in the volatile region. Somalilanders deserve the justice of having their decades-long practice of independence recognized and should be allowed to disassociate from the dysfunction of southern Somalia that hinders their development.

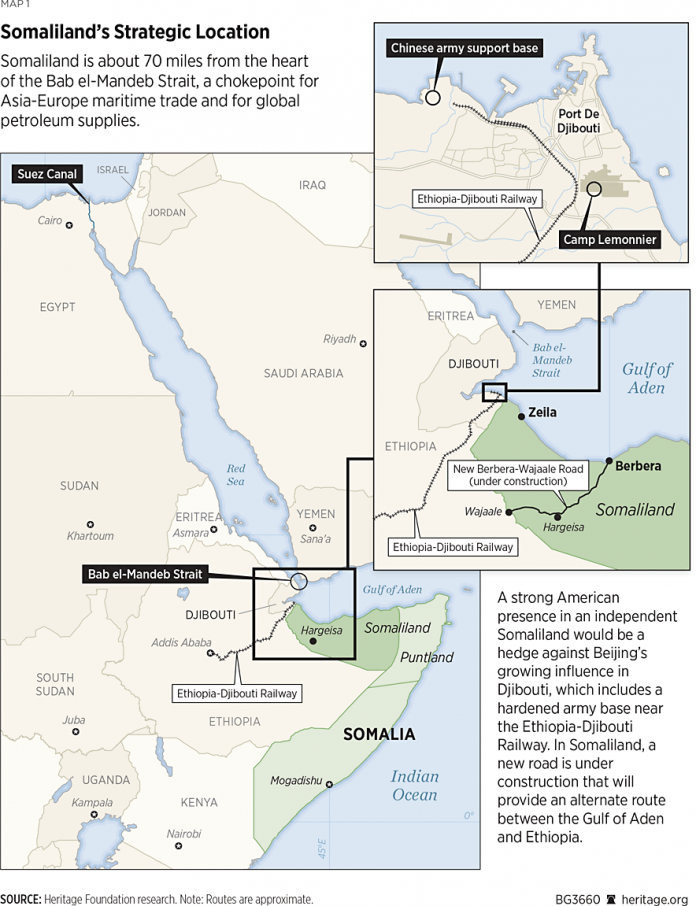

The autonomous territory of Somaliland sits in one of Earth’s most strategically important areas. Yet the influence Beijing has built, particularly in Djibouti, threatens the U.S.’s ability to defend its interests there. Recognizing Somaliland would let the U.S. build a partnership with the territory that would give Washington a hedge against further deterioration of its position in Djibouti. Hargeisa (the capital and largest city of Somaliland), almost alone in Africa, has already demonstrated its willingness to defy Beijing when it established what is, after Eswatini, Taiwan’s most advanced diplomatic relationship in Africa.

Recognizing Somaliland would also affirm American support for democracy by rewarding the territory’s tenacious, though still-developing, 30-year-old homegrown democracy. It would as well allow Washington to provide the type of unfettered support for democracy-building activities in Somaliland that it cannot currently provide because of constraints imposed by the federal government based in Mogadishu. Somaliland is also an area of relative calm that offers the U.S. an opportunity to work with an advantageously positioned partner that carries few of the risks and constraints that undermine Washington’s efforts elsewhere in the region.

A common objection to recognizing Somaliland’s statehood is that it would set off a brushfire of secession in Africa. Yet Eritrean and South Sudanese independence did not. Somaliland is also unique in Africa because it has successfully operated autonomously for 30 years, has a critical mass of the attributes of statehood, was once independent, and wishes to revert to that status within colonial-era borders, the standard the African Union uses to determine statehood.1

The AU’s precursor, the Organisation of Africa Unity, declared in 1964 that the assembled heads of state and government “[s]olemnly declare[] that all Member States pledge themselves to respect the borders existing on their achievement of national independence.” This should not be a bar to Somaliland independence since Hargeisa wishes to revert to the borders it had when it received independence from Britain. There is also an irony in using the Organization of African Unity declaration as justification for denying Somaliland independence because the summit that produced the pledge was held in Cairo—then part of the United Arab Republic after Egypt and Syria voluntarily united in 1958. That union was dissolved in 1961 after Syria declared its independence, and African states today recognize Syria’s sovereignty. They also recognize that of the Sudanese Republic (today known as Mali) and Senegal, conjoined in the Mali Federation that became independent in 1960 but voluntarily dissolved several months later. For the OAU declaration, see Organization of African Unity, “Resolutions Adopted by the First Ordinary Session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government Held in Cairo, UAR, from 17 to 21 July 1964,” July 1964, https://au.int/sites/default/files/decisions/9514-1964_ahg_res_1-24_i_e.pdf (accessed August 6, 2021).

Recognition of its independence would delegitimize other secessionist movements’ claims by establishing a difficult standard for achieving sovereignty.

Independence would free Somaliland from the drag of association with southern Somalia. It would also deliver the justice of honoring the strongly and consistently held aspirations for independence of millions of Somalilanders.

History

The region of Somalia today known as Somaliland achieved independence from Britain on June 26, 1960, following 73 years as a British protectorate. Five days later it formed the Somali Republic by joining with southern Somalia when the latter gained its own independence from Italy.

Initial Merger. Despite the voluntary merger, tensions existed between Somaliland and the rest of the country from the beginning. Of the Somalilanders who voted—the leading political party there boycotted the process—over 60 percent rejected a 1961 referendum ratifying the union and a provisional constitution for the Somali Republic.2

One day after independence, Somaliland’s Legislative Assembly passed the Union of Somaliland and Somalia law that was never ratified in the south. The southern legislature instead passed a different law repealing the north’s legislation. Northerners had little input on the constitution that southerners and Italian officials drafted, which provoked the widespread resistance in Somaliland to the new union law and the constitution. See Anthony J. Carroll and B. Rajagopal, “The Case for the Independent Statehood of Somaliland,” American University International Law Review, Vol. 8, Nos. 2–3 (Winter/Spring 1992 and 1993), https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1877&context=auilr (accessed August 6, 2021), and Initiative and Referendum Institute, Somaliland National Referendum: Final Report of the Initiative & Referendum Institute’s Election Monitoring Team, July 27, 2001, http://www.iandrinstitute.org/docs/Final-Somaliland-Report-7-24-01-combined.pdf (accessed August 6, 2021).

A failed coup in Somaliland by a secessionist faction followed later that year; while a brief calm settled on relations after a Somalilander became prime minister in 1967, it shattered two years later when the dictator Mohamed Siad Barre came to power.3

The prime minister from Somaliland, Mohammed Ibrahim Egal, spent all but six months of the next 13 years in prison. David H. Shinn, “Somaliland: The Little Country That Could,” Center for Strategic and International Studies Africa Notes No. 9, November 2002, https://wayback.archive-it.org/all/20090225023746/http:/somaliuk.com/Indepth1/country_that_could.pdf (accessed August 6, 2021).

Rebellion. Barre’s brutal rule eventually sparked a rebel movement in Somaliland and in other parts of the country. During the subsequent civil war, government-backed forces killed tens of thousands of Somalilanders and forced half a million people to flee to Ethiopia. Hargeisa and other important northern cities were virtually destroyed.4

In three years alone, as many as 800,000 landmines were strewn throughout Somaliland. “Somaliland,” Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, http://archives.the-monitor.org/index.php/publications/display?url=lm/2004/somaliland.html#fn9517 (accessed August 6, 2021).

Barre fell in 1991, but the violence throughout southern Somalia continued. The rapaciousness of the warlords battling for control brought famine to the country, prompting an international intervention that led to the infamous Black Hawk Down battle, in which 19 U.S. servicemen were killed. The Islamist terrorist groups the Islamic Courts Union, and then its successor, al-Shabaab, eventually seized swathes of southern Somalia. While an international military force has pushed al-Shabaab from many of its strongholds, it remains potent in the south.

De Facto Independence. Somaliland charted a different course. Following a conference of traditional leaders, in May 1991 the territory re-declared independence and began operating as an autonomous state. A series of other conferences followed in which the leadership created a system of government mixing traditional and Western-style elements that remains largely in place today. It held a de facto independence referendum in May 2001—in which 97 percent of voters approved a constitution that again proclaimed the region’s independence.5

An estimated two-thirds of eligible voters participated. Those who voted “no” on the referendum likely were expressing displeasure with Somaliland’s political leadership—and not with the notion of independence—while those who voted positively seemed primarily motivated by wanting to support Somaliland’s independence claim. Some of those who abstained were likely opposed to independence, however. Turnout was much lower in the eastern part of Somaliland (inhabited by clans different from Somaliland’s dominant clan, the Isaaq), an area also claimed by neighboring Puntland. The contested areas are dominated by the Dulbahante and Warsangeli, sub-clans of the Harti (itself a sub-clan of the Darod), which is also prominent in Puntland. These non-Isaaq clans generally prefer union with Puntland and so oppose Somaliland independence, although it is unclear the exact number who oppose independence. Initiative and Referendum Institute, Somaliland National Referendum, and Shinn, “Somaliland: The Little Country That Could.”

The territory has held seven popular votes since re-declaring independence, including three presidential elections that included in 2010 a defeated incumbent leaving office peacefully.6

Saeed Shukri, “Unrecognized Vote: Somaliland’s Democratic Journey,” The Elephant, May 3, 2021, https://www.theelephant.info/long-reads/2021/05/03/unrecognized-vote-somalilands-democratic-journey/ (accessed August 6, 2021).

During the most recent legislative elections held in May—elections largely financed by Somaliland itself7

Brenthurst Foundation, “Report of the Brenthurst Foundation: Somaliland Election Monitoring Mission (SEMM),” June 1, 2021, https://www.thebrenthurstfoundation.org/downloads/semm-final-report-1.pdf (accessed August 6, 2021).

—the two opposition parties combined to win most of the seats and formed a coalition that gives them an absolute parliamentary majority.8

“Somaliland Opposition Joins Forces to Grab Control of Parliament,” Yahoo News, June 6, 2021, https://news.yahoo.com/somaliland-opposition-joins-forces-grab-170126407.html (accessed August 6, 2021).

Each of the popular votes has suffered deficiencies, but none serious enough to derail the territory’s democracy.9

The international teams observing the elections throughout the years often praise their conduct. For examples, see European Union, “Report on the Somaliland Local Elections Held on 15 December 2002,” Delegation of the European Commission in the Republic of Kenya, https://aceproject.org/ero-en/regions/africa/SO/somaliland-report-local-elections-of-15-december (accessed August 6, 2021); International Republican Institute, “Somaliland September 29, 2005, Parliamentary Election Assessment Report,” https://www.iri.org/sites/default/files/fields/field_files_attached/resource/somalilands_2005_parliamentary_elections_assessment.pdf (accessed August 6, 2021), and Brenthurst Foundation, “Report of Brenthurst Foundation.”

Somaliland has not been entirely free of instability. The Somali National Movement that led the territory in its initial independence fight (and then against Barre) fractured in the early 1990s, sparking a nine-month civil war. Clan and political violence, the causes of which often overlapped, periodically flared as well.

Safety and Union. Nonetheless, Somaliland today is far safer than southern Somalia—and freer than most African countries.10

Somaliland was listed as “Partly Free” in the latest Freedom in the World report. Its score puts it in the top 50 percent of African countries; only Kenya has a better score in the East Africa region. Freedom House, Freedom in the World, 2020, https://freedomhouse.org/countries/freedom-world/scores (accessed September 14, 2021).

The series of conferences that produced Somaliland’s governance model succeeded by the mid-1990s in ending much of the territory’s internal violence,11

International Republican Institute, “Somaliland September 29, 2005, Parliamentary Election Assessment Report.”

and al-Shabaab, despite its strength in southern Somalia, has little presence in Somaliland. The most significant source of conflict currently affecting the territory is a long-simmering border dispute with the neighboring Puntland region that occasionally sparks armed clashes.

When there is a government in Mogadishu, it repudiates Somaliland’s independence, but lacks the authority to stop it. While Mogadishu considers Somaliland a federal member state and allots it seats in the national parliament, Hargeisa makes it illegal for any of its citizens to participate.12

Anyone from the territory who holds a position in the federal government is not allowed back into the territory. Once he has left office, his clan can file for a pardon from the Somaliland president that, if granted, would allow him to return. For the original citation, see Joshua Meservey, “U.S. Must Press Somalia to Deliver Competent Governance,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3252, October 5, 2017, https://www.heritage.org/global-politics/report/us-must-press-somalia-deliver-competent-governance. Note: The prime minister referenced in footnote 3 is the prime minister of Somalia, before Somaliland re-declared independence in 1991. The head of government today in Somaliland is the president.

Southern Somalia lacks now—and for the far foreseeable future—the capacity to force Somaliland back into union.

It is also implausible that Somaliland will ever voluntarily rejoin southern Somalia. For 30 years it has stayed committed to independence, and the scars from the atrocities southern forces inflicted on it remain.

Recognition Benefits for the U.S.

Recognizing Somaliland would be a simple acknowledgement of the truth that the territory is an independent state in all but a technical sense—and would allow Washington to create a more effective reality-based policy for the region. The benefits to the U.S. would be significant, starting with allowing Washington to diversify away from Djibouti, a country on which it is overly reliant and that is increasingly under Chinese influence.

The region in which Djibouti and Somaliland lie is among Earth’s most strategically important. In recognition of that fact, the U.S. placed its only permanent military base in Africa in Djibouti.13

This small country the size of New Hampshire hosts Chinese, French, German, and Japanese military bases as well. The port is critical to U.S. military operations in Africa, as 90 percent of the logistics and materiel U.S. Africa Command uses in its East Africa operations flow through Djibouti port. See Thomas D. Waldhauser, “Statement of General Thomas D. Waldhauser, United States Marine Corps Commander, United States Africa Command, Before the Senate Committee on Armed Services,” February 7, 2019, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate, https://www.africom.mil/document/31480/u-s-africa-command-2019-posture-statement (accessed August 6, 2021).

Yet despite the U.S. presence, few other countries in the world are so under Chinese sway as Djibouti.

Beijing recently built in Djibouti its only overseas military base, a hardened encampment whose quay can support a Chinese aircraft carrier.14

The Chinese government considers Djibouti an “overseas strategic strongpoint,” which scholars have defined as “foreign ports with special strategic and economic value that host terminals and commercial zones operated by Chinese firms.” Peter A. Dutton, Isaac B. Kardon, and Conor M. Kennedy, “Djibouti: China’s First Overseas Strategic Strongpoint,” China Maritime Studies Institute China Maritime Report No. 6, April 2020, https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1005&context=cmsi-maritime-reports (accessed August 6, 2021).

Beijing’s lavish financing of Djiboutian infrastructure has made Djibouti at high risk of debt distress,15

John Hurley, Scott Morris, and Gailyn Portelance, “Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective,” Center for Global Development, March 2018, https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/examining-debt-implications-belt-and-road-initiative-policy-perspective.pdf (accessed August 6, 2021).

and China is by far Djibouti’s largest trading partner.16

In 2019, trade between Djibouti and China was worth $2.2 billion. The value of Djibouti’s trade with its second-largest partner, India, was $377 million. “Djibouti,” Observatory of Economic Complexity, https://oec.world/en/profile/country/dji/ (accessed August 6, 2021).

The Chinese government financed—and Chinese companies built—sensitive Djiboutian buildings such as the foreign ministry headquarters and the People’s Palace.17

Joshua Meservey, “Government Buildings in Africa Are a Likely Vector for Chinese Spying,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3476, May 20, 2020, https://www.heritage.org/asia/report/government-buildings-africa-are-likely-vector-chinese-spying (accessed August 6, 2021).

State-controlled China Merchants Port Holdings manages three of Djibouti Port’s terminals.18

In addition to being legally required, as are all Chinese companies, to cooperate with the Chinese government on sensitive activities such as intelligence collection, China Merchants Port Holdings is majority owned by China Merchants Group, a state-owned enterprise. For a description of China Merchants’ control of the Djibouti port’s terminals, see “AFRICOM Chief Warns of Chinese Control at Port of Djibouti,” Maritime Executive, March 15, 2018, https://www.maritime-executive.com/article/u-s-concerned-by-chinese-presence-at-port-of-djibouti#gs.EE29ho0 (accessed August 6, 2021), and Costas Paris, “China Tightens Grip on East African Port,” Wall Street Journal, February 21, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-tightens-grip-on-east-african-port-11550746800 (accessed August 6, 2021).

It and four other Chinese companies are involved in various ways in the ownership, construction, and operation of what will be Africa’s largest free trade zone, the Djibouti International Free Trade Zone.19

Dutton, Kardon, and Kennedy, “China Maritime Report No. 6: Djibouti: China’s First Overseas Strategic Strongpoint,” and Thierry Pairault, “The China Merchants in Djibouti: From the Maritime to the Digital Silk Roads,” Africanews, September 12, 2019, https://www.africanews.com/2019/03/12/the-china-merchants-in-djibouti-from-the-maritime-to-the-digital-silk-roads-by-thierry-pairault// (accessed August 6, 2021).

Beijing’s unparalleled influence in the country has already impeded American operations20

In 2018, military-grade lasers fired from the Chinese base targeted U.S. military aircraft an unspecified number of times, in one instance causing minor injuries to two U.S. airmen. The U.S. also accused China of using drones to interfere with American planes and of trying to restrict American use of international air space in the area. Geoff Hill, “China, U.S. Military Clash over Djibouti Airspace,” Washington Times, June 16, 2019, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2019/jun/16/china-us-military-clash-over-djibouti-airspace/ (accessed August 6, 2021), and Aaron Mehta, “Two U.S. Airmen Injured by Chinese Lasers in Djibouti, DOD Says,” Defense News, May 3, 2018, https://www.defensenews.com/air/2018/05/03/two-us-airmen-injured-by-chinese-lasers-in-djibouti/ (accessed August 6, 2021).

—and positions China to shut down U.S. activity in the case of a confrontation between the two countries.21

Joshua Meservey, “China’s Strategic Aims in Africa,” testimony before the U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission, May 8, 2020, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Meservey_Testimony.pdf (accessed September 14, 2021).

The U.S. must compete in Djibouti, but a strong American presence in an independent Somaliland would be a hedge against the U.S. position continuing to deteriorate in Djibouti. Somaliland has more than 500 miles of coast on the Gulf of Aden that abuts the Indian Ocean and is directly across the water from conflict-torn Yemen, where Iranian-backed militias and an al-Qaeda affiliate operate.22

Zeila in Somaliland is about 140 miles from Aden, the capital of Yemen, and about 90 miles from the nearest point on Yemen’s coast. It is approximately 85 miles in a straight line from the heart of the Bab el-Mandeb Strait as well.

Its nearest point is about 70 miles from the heart of the Bab el-Mandeb Strait—through which around 9 percent of the world’s maritime-borne petroleum and much of Europe–Asia sea trade transits.23

U.S. Energy Information Administration, “The Bab el-Mandeb Strait Is a Strategic Route for Oil and Natural Gas Shipments,” August 27, 2019, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=41073 (accessed August 6, 2021). The Strait is likely to only grow in importance because Saudi Arabia has been increasing its capacity to ship oil from its Red Sea terminals to diversify away from the Strait of Hormuz. “Yanbu South Terminal Export Capacity,” Saudi Aramco, October 17, 2018, https://www.aramco.com/en/news-media/news/2018/yanbu-south-terminal-export-capacity (accessed August 6, 2021).

This strait is also part of the quickest route for the Mediterranean-based U.S. 6th Fleet and the Indian Ocean–based 5th Fleet to rendezvous during a conflict or other crisis. Somaliland is in the East Africa region that has the continent’s second-most populous country, Ethiopia, which, along with neighboring Kenya, was among Africa’s most vibrant economies in pre-pandemic times. Djibouti and Mombasa in Kenya are the only two large, modern ports serving the region, which gives Somaliland’s Berbera port an opportunity to emerge as an economic hub.24

Land-locked Ethiopia owns a 19 percent stake in Berbera as it seeks to diversify away from Djibouti, through which virtually all its trade currently passes. However, a recent report claimed that Ethiopia missed a deadline for buying a share in the Berbera port, so the fate of the deal is unclear. A United Arab Emirates’ company, DP World, is expanding and renovating the Berbera port. Somaliland’s Zeila port is also known as Saylac. The harbor there currently cannot accommodate modern cargo vessels because it is filled with silt, and port infrastructure is virtually nonexistent. According to a senior Somaliland official, however, it would be possible to clean and deepen the harbor and add a breakwater to enable it to receive modern cargo vessels. Zeila is Somaliland’s closest port to Ethiopia. For details on the Berbera renovation, see “DP World and Somaliland Open New Terminal at Berbera Port, Announce Second Phase Expansion and Break Ground for Economic Zone,” DP World, June 24, 2021, https://www.dpworld.com/news/releases/dp-world-and-somaliland-open-new-terminal-at-berbera-port-announce-second-phase-expansion-and-break-ground-for-economic-zone/ (accessed August 6, 2021). For the report claiming Ethiopia missed a deadline for ownership in Berbera, see Andres Schipani, “Somaliland Gears Up for ‘Healthy’ Battle of Ports,” Financial Times, September 2, 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/f928ecda-2c96-4957-ae3c-94be56385fcf (accessed September 14, 2021).

Beyond shoring up its position that Beijing is undercutting in an important region, recognizing Somaliland would help the U.S. in other ways as well. Hargeisa and Taipei established close informal relations in 2020, and subsequently exchanged representatives. An independent Somaliland would give Taiwan another country willing to have such ties with it, thereby boosting a territory that the U.S. also supports. By serving as a maritime gateway for East Africa not under Chinese influence, Somaliland could also complicate the continuity of the Belt and Road infrastructure that Beijing is building in the region.25

“Somaliland and Taiwan: Two Territories with Few Friends But Each Other,” BBC, April 13, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-56719409 (accessed August 6, 2021).

At a time when illiberal governance is advancing in parts of Africa, American recognition of Somaliland would be a way to help a prominent experiment in democracy address its shortcomings, something Washington cannot currently do fully because of constraints imposed by Mogadishu. Problems with Somaliland’s democracy have included deadly—though limited—post-election clashes and elite power struggles that have twice necessitated years-long extensions of the president’s term. Although the territory’s most recent vote was hailed as free and fair, it was 16 years overdue because of wrangling among Somaliland’s political parties.26

The elections have also frequently included accusations by one contesting party or another of irregularities that required resolution in court. However, the fact that these disputes proceeded through a judicial process (the outcome of which was respected by the litigants), testifies to the strength of Somaliland’s institutions that are necessary to safeguard and deepen any country’s democratic system. For documentation of some of Somaliland’s democratic challenges, see Shukri, “Unrecognized Vote: Somaliland’s Democratic Journey.”

The government also arrested five opposition candidates prior to the election.27

“Somaliland Elections: Could Polls Help Gain Recognition?” BBC, May 31, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-57255602 (accessed August 6, 2021).

Despite those challenges, Somaliland is peaceful. It has largely quelled al-Shabaab, and its border dispute with Puntland, while concerning, is localized and the occasional clashes are small-scale. The territory’s stability distinguishes it in a tumultuous region. A civil war rages in Ethiopia, Sudan is undertaking a hopeful but difficult and uncertain political transition, Eritrea is an authoritarian pariah, South Sudan could return to civil war at any moment, and a contentious election looms in Kenya, which has had violent polls in the past. Amid all this instability, Washington should be seeking out areas of calm, with Somaliland being the obvious option. The danger there that U.S. efforts will be wiped away by war or unrest is lower than in arguably any country in the region.

Formalizing Somaliland independence might also focus the Mogadishu elites’ minds on the task of governing. Power struggles within southern Somalia’s political class have plunged the country into one crisis after another. The ongoing electoral process in the south is a dramatic regression from the previous (also deeply flawed) electoral process,28

Joshua Meservey and Joseph McAndrew, “A Closer Look at Somalia’s Uninspiring Electoral Process,” Heritage Foundation Commentary, January 20, 2021, https://www.heritage.org/africa/commentary/closer-look-somalias-uninspiring-electoral-process. The electoral process has worsened since the cited article was written.

in large part because of the elites’ inability to mediate their disputes. The specter of other federal states seeking greater autonomy could jolt Mogadishu’s elites from their absorption with political battles.

There is, as well, a strain within Somali nationalism that seeks to reunite the predominantly ethnic Somali regions of northeast Kenya, Djibouti, and eastern Ethiopia with Somalia. It is a long-running source of tension in the region, and an independent Somaliland might undermine this destructive irredentism by making its realization even more unlikely than it already is.

Finally, it would be an act of justice to recognize Somaliland. Millions of Somalilanders have repeatedly affirmed that they wish to live in their own independent state, and their government has consistently demonstrated its independence.29

In 2009, The Heritage Foundation recommended that the international community recognize Somaliland’s independence “pending demonstrable actions of improved governance and order.” Twelve years later, Somaliland has met that standard. See Brett D. Schaefer, “Piracy: A Symptom of Somalia’s Deeper Problems,” Heritage Foundation Web Memo No. 2398, April 17, 2009, https://www.heritage.org/africa/report/piracy-symptom-somalias-deeper-problems#_ftnref8.

The fact that the world generally views Somaliland as indistinguishable from the far more unstable and undemocratic southern Somalia denies Somaliland the benefits of the engagement it would attract on its own merits. U.S. recognition of Somaliland would partially rectify this injustice by sending a strong signal that the territory is distinct from the rest of Somalia, thereby encouraging investment and trade from the U.S. and others.

The Risks of Recognition

Recognizing Somaliland would bring some objections and risks of which Washington should be aware.

Competitor Countermoves. Beijing might try to isolate the new country. As previously noted, American recognition of Hargeisa would provide indirect diplomatic support to Taiwan. The Chinese government could lean on countries with which it has significant influence, such as Ethiopia, Kenya, and the United Arab Emirates, to pressure Somaliland to dial down its relationship with Taiwan.

Even if Beijing took this tack, however, it should not change the U.S.’s calculation. A pressure campaign by the Chinese government would only drive Somaliland closer to Washington. The U.S. should also have a plan for economic and diplomatic exchange with Hargeisa before formal recognition, thereby helping the new country weather possible pressure.

The greater danger is that the Chinese government would try to degrade Somaliland’s relationship with Taiwan and the U.S. by wooing its leadership with lavish aid packages or personal inducements, as it has done with many other African governments.30

Joshua Meservey, “China’s Palace Diplomacy in Africa,” War on the Rocks, June 25, 2020, https://warontherocks.com/2020/06/chinas-palace-diplomacy-in-africa/ (accessed August 6, 2021).

Somaliland resisted such blandishments previously31

Edwin Haroldson, “Somaliland: President Bihi Rebuffs China’s ‘Wolf Warrior’ Diplomats’ Pressure to Cut Ties with Taiwan,” Somtribune, August 6, 2020, https://www.somtribune.com/2020/08/06/somaliland-president-bihi-rebuffs-chinas-wolf-warrior-diplomats-pressure-to-cut-ties-with-taiwan/ (accessed August 6, 2021).

because Hargeisa likely calculated that spurning Beijing would win American favor.

This problem complicates all of the U.S.’s relationships with African countries, and Washington would have to meet it the same way it must meet it elsewhere: by making the benefits of a strong partnership compelling enough that Hargeisa would wish to maintain it no matter what Beijing does. Being the first to recognize Somaliland would also give the U.S. a head start on building enduring ties that would withstand a Chinese challenge.

It could be difficult for Hargeisa to demur if Beijing offered to not use its veto at the U.N. Security Council to block U.N. recognition of Somaliland independence in exchange for Somaliland spurning Taiwan. Ultimately, it would be up to Taipei to make the case to Hargeisa for why its diplomatic opening should continue, while the U.S.’s priority is its own interests in Somaliland.

Russia could try to use Somaliland independence to validate its claims that regions in Europe—such as South Ossetia and Abkhazia in Georgia and the so-called Luhansk People’s Republic and the Donetsk People’s Republic in Ukraine—deserve independence. These regions, however, are not analogous to Somaliland because none of them have as many of the prerequisites of statehood as Somaliland has. They were also illegally invaded and occupied by a foreign country—Russia—that continues to dominate them, whereas the Somaliland government is the final authority within its borders.

A Rupture with Mogadishu. One virtually certain consequence of Washington recognizing Somaliland is that it would damage relations with southern Somalia that would view it as dismembering the country. Yet Somaliland, in practice, is already separate from the rest of Somalia and has, for 30 years, repudiated Mogadishu’s sovereignty claims. Somaliland has taken the decision to carve itself off from the rest of the country, and American recognition of its independence would simply be acknowledging that reality.

While a break with Mogadishu would be unfortunate, it would not badly harm U.S. strategic interests because Washington derives little benefit from its current relationship with the federal government. Its political elites’ power struggles obstruct the battle against al-Shabaab,32

“Somali Government Troops Face Off With Forces Loyal to Sacked Police Boss,” Reuters, April 17, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/somali-government-troops-face-off-with-forces-loyal-sacked-police-boss-2021-04-17/ (accessed August 6, 2021).

and the rampant corruption siphons off American aid money and fuels further violent conflict.33

Katharine Houreld, “Exclusive: U.S. Suspends Aid to Somalia’s Battered Military Over Graft,” Reuters, December 14, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-somalia-military-exclusive-idUSKBN1E81XF (accessed August 6, 2021).

Despite massive military, diplomatic, and financial support, Mogadishu has made scant progress rectifying the many thorny issues facing the country.34

Meservey, “U.S. Must Press Somalia to Deliver Competent Governance”; Joshua Meservey, “Nearly Violent Confrontation in Somali Parliament Highlights Government’s Insufficiencies, Need for Accountability,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 4850, May 3, 2018, https://www.heritage.org/global-politics/report/nearly-violent-confrontation-somali-parliament-highlights-governments; Joshua Meservey, “A Growing Challenge for America’s Somalia Policy,” Heritage Foundation Commentary, January 10, 2020, https://www.heritage.org/africa/commentary/growing-challenge-americas-somalia-policy; and Meservey and McAndrew, “A Closer Look at Somalia’s Uninspiring Electoral Process.”

As mentioned earlier, American recognition of Somaliland may bring a unity and seriousness of purpose to the federal government facing the prospect of other attempted defections by its federal member states.

Somalia’s anger over American recognition could give China an advantage in the strategically situated country. However, Somalia badly needs American security assistance and humanitarian aid, which would dampen an overreaction from Mogadishu and likely facilitate an eventual rapprochement. And while Beijing could replace any American aid Mogadishu rejects, it could not and would not provide the kinetic counterterrorism support that the U.S. does, and which is important to keeping al-Shabaab at bay. Beijing has made some recent investments in Somalia and publicly proclaims its interest in strong diplomatic relations, but Somalia for the foreseeable future is unlikely to achieve enough stability to be the type of partner with which Beijing can build strong ties. There are also other countries with far more influence in Somalia than China,35

Turkey is probably the foreign country with the most influence in Somalia due to a long campaign by Ankara to build commercial, diplomatic, and military ties to Mogadishu.

which, even if they are friendly with Beijing, would limit the gains the Chinese government would make if the U.S. was evicted from Somalia.

Another problematic country for the U.S., Turkey, might also benefit from a Washington–Mogadishu rupture by replacing some of the withdrawn American counterterrorism assistance. Ankara already trains Somali forces and provides military materiel, and it has some experience and the willingness to engage in kinetic operations, such as in Libya. Yet while Turkey is a challenge for the U.S., it is not a strategic competitor like China or even Russia. Ankara also already enjoys a strong position in Somalia and may be unwilling to undertake significant extra effort and expense for marginal gain.

Consternation from African Countries. U.S. recognition would likely disturb some African states who fear that Somaliland’s example would encourage secessionist movements within their own borders. However, the most recent examples of African countries receiving independence—Eritrea in 1991 and South Sudan in 2011—did not ignite a secessionist brushfire throughout Africa. Somaliland’s claim (as the African Union’s own fact-finding mission recognized in 2005)36

The report stated, “Somaliland’s search for recognition [is] historically unique and self-justified in African political history…. [T]he case should not be linked to the notion of ‘opening a pandora’s box’ [original emphasis]. As such, the AU should find a special method of dealing with this outstanding case.” African Union, “AU Fact-Finding Mission to Somaliland (30 April to 4 May 2005),” 2005, http://www.somalilandlaw.com/AU_Fact-finding_Mission_to_Somaliland_2005_Resume.pdf (accessed August 6, 2021).

is also unique because there is no other territory in Africa that was once independent before voluntarily joining a union it now wants to leave—and which has successfully operated for 30 years as a de facto sovereign state.37

Today, Somaliland has its own currency, passport, foreign policy, and standing army, and maintains control of the land it claims—making it a genuinely unique African secessionist movement.

That means that recognizing Somaliland would raise the standard for recognition of secessionist movements in Africa.

Somaliland Failure. It is possible that Somaliland could fail, as did the world’s newest country, South Sudan, and reflect poorly on Washington. However, this is a remote possibility, as the territory has proven for three decades its ability to competently govern itself and has developed a habit of democracy and the institutions that help protect it. The territory, in fact, possesses a track record far superior to South Sudan’s at independence.

A greater risk is that recognition leads to a surge in development assistance that triggers elite competition and disrupts Somaliland’s tradition of independence and self-reliance that likely accounts for much of its success. The plan that the U.S. should have in place before recognition must account for this danger by ensuring that any American aid is limited, targeted, and accounted for. The focus of the U.S.’s post-recognition strategy should be on providing diplomatic support and motivating and facilitating mutually beneficial trade and private investment.

Lesser But Real Risks. There is also the slight danger of reputational harm to the U.S. if no other country follows its lead in recognizing Somaliland’s independence.38

The U.S.’s reputation was not noticeably harmed by its recognition in 2008 of Kosovo, which still does not have U.N. membership (primarily because of Russian opposition). The situation is not a perfect parallel with Somaliland’s, however, since around 100 countries recognize Kosovo.

It is true that it will be difficult for Somaliland to gain a U.N. seat, as that would require a positive recommendation from the Security Council on which China permanently sits, and then approval by the General Assembly.39

United Nations, Rules of Procedure of the General Assembly, A/520/Rev.19 (2021), https://www.un.org/en/ga/about/ropga/ropga_adms.shtml (accessed August 6, 2021).

Yet Washington leading the way would probably give the diplomatic cover some states require before proceeding with unilateral recognition.40

Former Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Tibor Nagy informed the author that when he was U.S. ambassador to Ethiopia, then-Somaliland President Egal told him there were countries that were willing to be the second states to recognize an independent Somaliland. An Ethiopian government official confirmed to Nagy the truth of Egal’s claim.

Even if no other country recognized Somaliland, it would not lessen the advantages the U.S. would receive. It could even make Somaliland hew more closely to Washington as its staunchest international partner.

There are other concerns about which Washington must be vigilant, including the possibility that Somaliland and Puntland’s slow-boil border conflict could escalate, although that risk would exist with or without American recognition of Somaliland’s independence. Hargeisa has also at times cracked down on press freedom, and the territory is dominated by the Isaaq clan, while members of minority clans do not hold a single seat in the House of Representatives.41

Given the deeply divisive effect clans have on Somali politics and society, stability in any region of Somalia may require that one clan be dominant. That dominance must, however, be coupled with a commitment to protecting minority clans’ rights and giving them the same opportunities dominant clan members receive, otherwise it would be a repressive system that would likely lead to its own type of unrest and violence. For Isaaq dominance in Somaliland, see “Somaliland Elections: Could Polls Help Gain Recognition?”

These problems are serious, but Washington can best help Hargeisa solve them through the vigorous sort of engagement that can only come by recognizing Somaliland.

Getting It Right

The U.S. should strengthen its position in the critical East Africa region by recognizing Somaliland. The executive and legislative branches will have the largest roles to play. To wit:

- Relevant congressional committees should hold hearings on recognizing Somaliland. This would raise the profile of the issue and give Congress the opportunity to study the benefits of recognition and how to avoid possible pitfalls.

- A bipartisan congressional delegation should travel to Somaliland. This would demonstrate support for the territory, help Congress better understand its opportunities and problems, and assist Congress in determining how to render aid most effectively.

- Congress should passa resolution expressing the sense of Congress that Washington should recognize Somaliland as a sovereign country. Doing so would put a powerful, co-equal branch of government on the record as supporting Somaliland’s independence and give the executive another reason for recognizing Somaliland.

- Before recognition, the U.S. should create a plan for locking in a beneficial relationship with Somaliland. This should include a commission of public- and private-sector representatives with relevant expertise who will create specific, actionable recommendations for incentivizing U.S. companies to invest in Somaliland; helping Hargeisa improve its business environment; mobilizing the backing of the Somaliland diaspora in the U.S.; and diplomatically supporting the new country. The recommendations should include whether and what types of U.S. aid would be effective in Somaliland, the appropriate amount of that aid, and how it should be delivered.

- The U.S. should determine what other countries, particularly in Africa, will follow an American lead on recognizing Somaliland. The U.S. should coordinate the timing of its recognition of Somaliland with these countries so they can prepare to follow in quick succession. Their doing so would create momentum for even more states to recognize Somaliland by signaling that it is safe and beneficial to have relations with Hargeisa.

- Before recognition, the U.S. should secure specific commitments from Somaliland to improve press freedom, refrain from politically motivated arrests, and ensure equal opportunities for minority clan members to gain political representation. Washington and Hargeisa should jointly create a plan for bilateral cooperation on helping Somaliland fulfill these commitments.

- The U.S. should recognize Somaliland as an independent country. In the U.S. system, this authority rests with the executive branch, which would need to make the decision and then take appropriate implementing steps, such as nominating an ambassador.

- Congress should back an executive branch decision to recognize Somaliland. This could be done by authorizing multi-year assistance for the activities necessary to implement relations between Washington and Hargeisa by, for example, funding a fully staffed embassy.

- The U.S. should offer to mediate the Somaliland–Puntland border dispute. This would mobilize an international effort to help resolve the issue. Washington should include partners like the United Arab Emirates, which is influential in both Somaliland and Puntland.

Conclusion

Recognizing the fact of Somaliland’s independence would bring significant benefits to the U.S. with few and manageable downsides. As the U.S.–China competition grows more intense, recognizing Somaliland would be a proactive way for the U.S. to defend its interests in Africa, a continent that provides significant aid to Beijing’s international agenda, often to Washington’s detriment.42

Joshua Meservey, “China Considers Big Data a Fundamental Strategic Resource, and Africa May Offer an Especially Valuable Trove,” in Walter Lohman and Justin Rhee, eds., 2021 China Transparency Report, Heritage Foundation, 2021, http://thf_media.s3.amazonaws.com/2021/China_Transparency_Report.pdf.

Recognition would also boost the U.S.’s democracy agenda by rewarding a government and its people who have lived a sincere commitment to democracy for three decades and enable Washington to offer unfettered support to help them further develop representative government. Recognition would also give the U.S. a relatively stable partner that carries little risk American efforts there will be undone by an explosion of unrest. Finally, it would be just to reward the millions of Somalilanders who, in their wish to have true and total independence against heavy odds, built a de facto country that is largely democratic—and at peace.

By Joshua Meservey

Joshua Meservey is Senior Policy Analyst for Africa and the Middle East in the Douglas and Sarah Allison Center for Foreign Policy, of the Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for National Security and Foreign Policy, at The Heritage Foundation.

Joshua Meservey is Senior Policy Analyst for Africa and the Middle East in the Douglas and Sarah Allison Center for Foreign Policy, of the Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for National Security and Foreign Policy, at The Heritage Foundation.