Nairobi slammed the UN court after it gave Somalia control over an oil and gas rich chunk of the Indian Ocean.

Kenya has rejected “in totality” the decision by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to favour Somalia in a years-long dispute over the two countries’ maritime border, adding that it is “profoundly concerned” over the decision and its implications on the region.

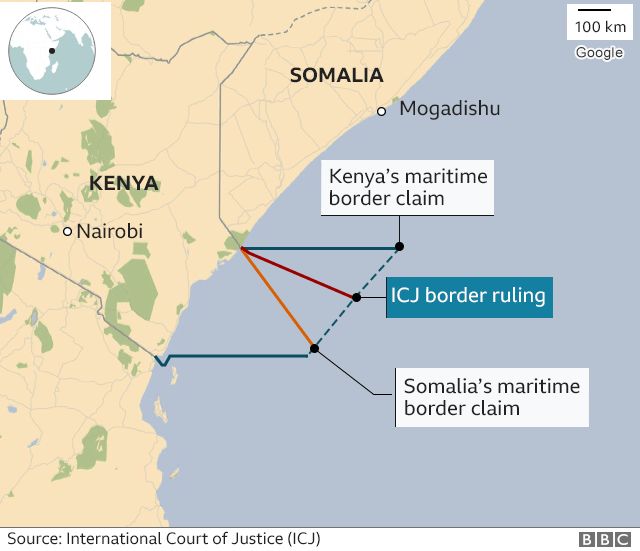

On Tuesday, the Hague-based United Nations’ highest court drew a new border close to the one claimed by Somalia although Kenya kept a part of the 100,000 square-kilometre (39,000 square-mile) area.

“The decision was clearly erroneous,” read a statement by Kenya’s Presidency published on Wednesday, adding that the verdict “embodies a perpetuation of the ICJ’s jurisdictional overreach and raises a fundamental question on the respect of the sovereignty and consent of States to international judicial processes”.

The news was celebrated in Somalia where Osman Dubbe, minister of information, culture and tourism, congratulated the Somali people for having “succeeded in capturing our seas”.

“This success did not come easily but through struggle and sacrifice,” he added on Twitter. The 14-judge panel of the international court rejected an argument by Somalia that Kenya had violated its sovereignty by operating in its territorial waters. It had also asked for compensation from Kenya on this matter.

The Hague also said that there was no proof to backs Kenya’s claim that Somalia had previously agreed to its claimed border.

The court’s rulings are binding, though the court has no enforcement powers and countries have been known to ignore its verdicts.

What was the dispute about?

The dispute between Somalia and Kenya stems from a disagreement over which direction their border extends into the Indian Ocean.

While Somalia says the boundary should run in the same direction as the southeasterly path of its land border, Kenya argues the border should take roughly a 45-degree turn at the shoreline and run in a latitudinal line.

Such a move will give Kenya access to a larger share of the maritime area.

Apart from fishing, the disputed area is thought to be rich in oil and gas, with both countries accusing each other of auctioning off blocks before the ruling by the court.

Al Jazeera’s Malcolm Webb, reporting from the Kenyan capital Nairobi, said “the court has already said Kenya does not have any legal grounds to reject this judgement because it signed up to this court’s authority in the 1960s and can’t retroactively renege on that”.

“The question now is will Kenya accept this ruling. If it does not, it puts Somalia in a stronger position to seek support from the UN to seek diplomatic support in enforcing or obliging Kenya to uphold this ruling,” he said.

What has happened so far?

In 2014, Somalia asked the ICJ to rule on the case after out-of-court negotiations between the two countries aimed at settling the dispute broke down.

In February 2017, the court ruled it had the right to adjudicate on the case as judges rejected Kenya’s claim that a 2009 agreement between the neighbours amounted to a commitment to settle the matter out of court, stripping the ICJ of jurisdiction.

In June 2019, the ICJ said public hearings would take place between September 9 and September 14 that year, before pushing the start date to November 4 after granting a request by Kenya that said it needed time to recruit a new legal team.

The Kenyan side appealed the November dates, saying it needed up to a year.

The ICJ then moved the hearings to June 2020, but Kenya then requested another postponement, this time citing the pandemic.

The UN delayed the hearing till March 2021.

In January, Kenya wrote to the ICJ, requesting the hearing be delayed for a fourth time, claiming a map with crucial information that was set to be presented as evidence in the case has disappeared.

Somalia protested against such a move, and the ICJ said earlier this year that the hearings would commence on March 15.

Kenya decided to boycott the hearing, citing “perceived bias and unwillingness” of the ICJ “to accommodate requests for the delaying the hearings” as a result of the pandemic.

The Hague moved ahead hearing Somalia’s case, while using written evidence provided by Nairobi instead.

A week before the final verdict, Nairobi announced that it withdrew its participation from the case, as well as its recognition of the court’s compulsory jurisdiction.