The two wings of Somaliland-born politicos living in Mogadishu have yet to agree on the number of members each is to get on a commission to prepare the former Somalia colony for ‘selections’ of President and parliament.

One wing is led by the Senate – Upper House of the Federal Parliament – speaker, Abdi Hashi, and the other by Mehdi Guleid, the Deputy Prime Minister.

According to Somalia media sources, Abdi Hashi and the interim PM, Mohamed Hussein Rooble, could not agree on the division of a 15-member quota allotted for the Somaliland-born economic refugees in Mogadishu. PM Rooble, according to the sources, offered 5 members to Abdi Hashi’s wing setting the rest for his deputy and his followers.

PM Rooble, according to the sources, offered 5 members to Abdi Hashi’s wing setting the rest for his deputy and his followers.

Hashi rejected the number given him insisting that it should either be 50-50 or nothing.

Despite the fact that the Republic of Somaliland has been a better-governed, decidedly more stable, democratic government for the past 30 years since the collapse of the Somalia-dominated military regime, who is to select Somaliland-born members for parliamentary seats has been one of the more caustic issues which caused a wide schism between federal leaders and the opposition.

The Farmajo camp, since the 20 September 2020 agreement, had been playing a deck that aimed to keep a grip on who is going to be picked for the ‘Somaliland’ seats in order to keep them on leash. The opposition, aware of the strategy, blocked every move to put the Villa Somalia plan on the roadmap.

With or without an agreement on the issue between the two camps, the outcome will have the least effect on the Somaliland Republic since Somalilanders regard people claiming representation in Mogadishu as ‘political opportunists’ and many other epithets such as ‘economic refugees’, ‘political mercenaries’ and the like.

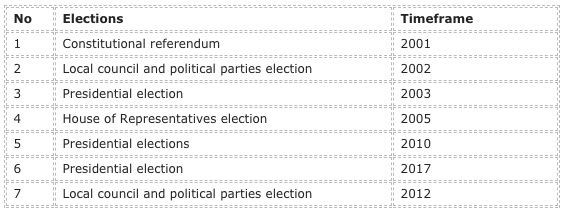

Somaliland is going into its 8th 1P-1V exercise to elect parliamentarians and local councillors on May 31 – a feat Somalia has yet to even attempt. Campaigning has already started with the three political parties of Kulmiye, Waddani and UCID each assigned a day until the 28th when all political rallies will stop to prepare for the poll day.

Campaigning has already started with the three political parties of Kulmiye, Waddani and UCID each assigned a day until the 28th when all political rallies will stop to prepare for the poll day.

Somalilanders – by and large – believe that if not for the unquestioned support of International aid partners, foreign missions in Somalia and regional and international organizations represented in Mogadishu, including the African Union and the United Nations, the weak, Villa Somalia-led government in Mogadishu would not have dared claim of jurisdiction over the Republic of Somaliland.

Somaliland merged with Somalia in a highly questionable manner on 1 July 1960.

In 1961, Somalilanders attempted to extricate themselves from the hasty act in a coup attempt and again in a referendum during which they showed their desire to back peddle. The Somalia-dominated government nibbed both attempts in the bud.

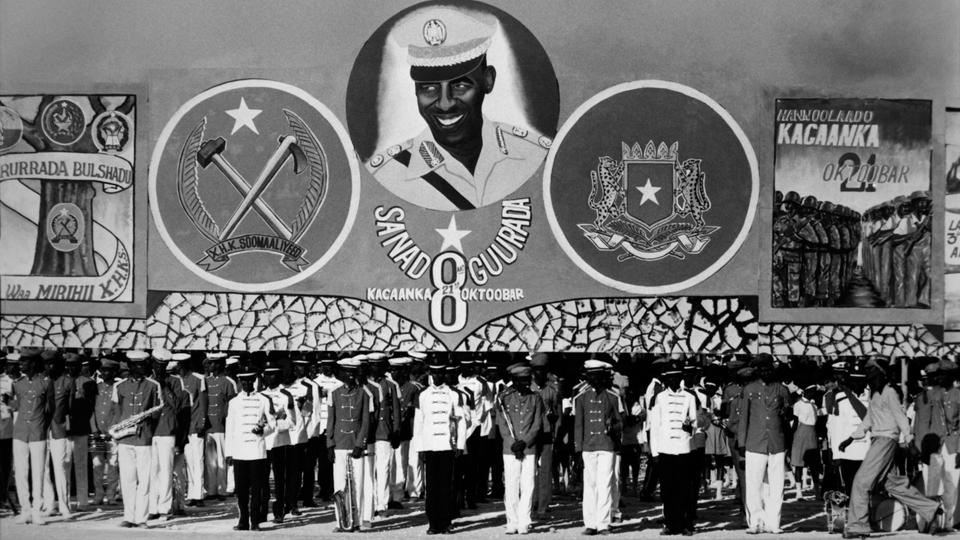

In 1969, a military junta ended the none-year life of civilian administrations abrogating all laws that strove to keep the loose patchwork of the two former states together.

Twenty-one years of persecution, economic strangulation and marginalization strategies aiming to completely cleanse resident Somalilanders of their land and supplant them with imported refugees from neighbouring Ethiopia and Somalia, followed.

An armed struggle which the Somali National Movement (SNM) started in 1981 ensued, ending in the overthrow of the military regime in January 1991 but after a costly spate of engagements leaving behind major cities in shambles, more than 200 000 confirmed deaths and nearly half a million more in refugee camps.

But a victorious Somaliland gathered all of its people together regardless of whose camp clans supported in a series of peacebuilding and reconciliations conferences which culminated in the grand, all-clan Burao conference at the end of which the restoration of Somaliland sovereignty was proclaimed by participants.  Since then, Somaliland has built a grassroots peacebuilding model the likes of which the world has not seen before.

Since then, Somaliland has built a grassroots peacebuilding model the likes of which the world has not seen before.

If that model was adopted in Somalia with the help of a fully recognized Somaliland Republic both the billions of dollars spent on security and aid and the years it has taken to even bring stakeholders to the same table would have been saved or used on more meaningful ventures.