Three albums of songs selected and digitised by Ostinato Records from the archives of Djibouti’s national broadcaster showcase the country’s diverse musical heritage

In a quiet corner of Djibouti’s national radio offices sits a small but densely packed room guarding one of the best preserved, yet largely unknown, cultural treasures of Africa.

Well maintained and air-conditioned, the chamber houses thousands of cassettes and master reels containing everything from political speeches to poetry and the region’s finest music. A unique collection of sounds silently and diligently stored since 1977, on the eve of independence of this small republic in East Africa bathed by the Red Sea.

The outstanding archives of the Radiodiffusion-Television de Djibouti is a vault of secrets and stories running from East Africa, Somalia and Ethiopia, and it accommodates nearly the entire musical output of the country since its establishment. Today, a meticulous group of young women trained in analogue technology in China takes care of the place.

“Out of all the archives I have visited in Africa, this was probably the best maintained and catalogued,” says Vik Sohonie, founder of Ostinato Records, a record label focusing on music from African countries with experience in trauma and displacement.

“It is great that in Djibouti, which is not a very rich country and has had a lot of cultural funding problems, somehow they still managed to keep this archive intact and going.”

In 2019, after three years of negotiations, Ostinato Records became the first foreign entity and the first label to be granted access to the archives of Djibouti’s national radio. The outcome is Djibouti Archives, a series of three albums, each featuring a different band of the country, mainly produced from the digitization of these historic recordings.

The Djibouti Archives

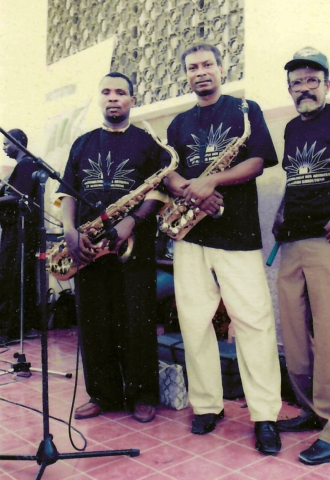

The first album of the series, Super Somali Sounds from the Gulf of Tadjoura, is a seminal anthology of the 40-member supergroup 4 Mars – Quatre Mars, in French – the band of Djibouti’s ruling party since its independence. The band was chosen to inaugurate the series because of its rich and singular music style that captures many cultures that have once passed through this part of the world.

4 Mars also offers a window into the country’s most recent past, when it was starting to build itself from scratch after gaining independence from France in June 1977. Earlier that year at the Afro-Arab Summit Conference held in Cairo, a number of Arab heads of state had called for strengthening the fight against imperialism and support for the struggles of, among other countries, Djibouti, which by September had joined the Arab League.

“Their music is phenomenal but it is also a great illustration of what Djibouti is and where Djibouti is,” Sohonie tells Middle East Eye. “The music of 4 Mars is probably the best evidence we have that this part of the world, at one point and even today, is the middle of Africa, Asia, and Europe in many ways.

“And 4 Mars is [also] an incredible insight into a young country building itself. They brought all its music as a very public enterprise.”

The band was born to serve as the cultural arm of the People’s Rally for Progress (RPP), Djibouti’s ruling party since 1979, and the name of the group is a direct reference to the founding date of the organisation in that same year. The newly born country decided to bring culture, and music in particular, under the state’s wing, given that its leaders saw it as an ideal resource to create a sense of pride.

‘4 Mars was at the time the spearhead for the construction of a national collective political consciousness’

– Rifki Abdoulkader

“4 Mars was at the time the spearhead for the construction of a national collective political consciousness,” says Rifki Abdoulkader, former deputy director of the Palais du Peuple, which directly supervised the band.

“The RPP put the means, the best poets, a selection of musical composers, equipment, and the salaries for [the whole] crew.”

In Djibouti, the authorities saw 4 Mars as the soundtrack to an independent era and the centrepiece of their efforts to decolonise culture.

But perhaps more importantly, Djibouti’s leaders saw the band as a means of sending people instructions and messages in their quest for a stable and successful future. Some of the titles of the album’s 14 tracks echo this will. The second and third songs, for instance, are called Hello, Peace! and Motherland, and others were named Compassion, Follow the Rules and Power.

“The crew was created to sensitise the people in several languages to important values such as unity, peace and progress: three basic points for the creation of a state and the construction of a nation. It was necessary to use the reigning orality to achieve these strategic objectives through poetry, theatre and songs,” said Abdoulkader, who is now special adviser to the prime minister on economic and trade development affairs.

For centuries, all roads led to the corner of East Africa where Djibouti lies. The Gulf of Tajoura is located at a major transit point, the Bab El Mandeb strait, connecting Africa, Asia, and the Mediterranean. This strategic location made it not only a valuable transit point for goods, but also a hub of ideas, peoples, and cultures that were exchanged, and eventually anchored, on its shores.

For this reason, Djibouti has been considered by some, such as filmmaker Louis Werner, as a cultural palimpsest where traces of the past, such as its well-rooted Islamic faith, which dates back to the times of Prophet Muhammad, show through to the present.

“When you hear 15 different cultures in their music, obviously, there must be something happening in Djibouti,” Sohonie says. “The album offers a new way of understanding history: we think of all roads leading to Rome, but I would argue that if we listen to the music of Rome, it does not have as many influences as the music of Djibouti.”

The influence of the Middle East and North Africa on Djibouti’s music essentially comes from Yemen, Egypt and Sudan. Because of its proximity to Yemen, Djibouti is home to a small, but significant, Yemeni community, part of which arrived long ago, while others have emigrated more recently, fleeing war in their country.

Sohonie notes that their musical rhythms are borrowed from Yemen and Egypt, and that their structures come from Sudan. The synth melodies, for their part, are Turkish-inspired.

Instrumentally and melodically, the album captures this melange of different cultures that transited through Djibouti at some point in history and which also came to characterise 4 Mars. The horns are influenced by Harlem jazz, the flutes derive from the tradition in Mongolia and China, the vocals are Somali with an influence of Bollywood, and the reggae is either from Jamaica or Somalia.

The rich album combines choral songs with solo pieces, and tracks in which the instrumentation is secondary, with others where it becomes important that vocals are being rhythmically and melodically led in the different sections of the composition.

The case of the third track, Motherland, is particularly interesting. The song is mainly choral and combines two groups of singers – one female and the other male – which are homorhythmic and share the same melody, at times alternating questions and answers and at times singing together, which conveys the feeling of unity and community.

The vocals of the songs are generally more traditional in their use of musical scales and ways of singing, yet the instrumentation is more innovative and becomes theatrical: it includes a mix of instruments and very different ways of playing, combining influences from jazz with reggae rhythms and lending a heavy role to synth melody and percussions.

“These are world-class musicians, and [the album] offers a great insight into the musical prowess of Djibouti and this part of Africa,” Sohonie says.

“It is an album that is really about shifting our entire perception of where good music was made, where the centres of our history lie, and where people are making amazing music. We can listen to music from a very small country like Djibouti and it can have a very universal appeal.”

Despite the fame it came to acquire, 4 Mars’s influence started to decline in the 1980s when most of the state funds that had sustained both the band and the national theatre began to dry up.

Another turning point for the group was the civil war that ravaged Djibouti from 1991 to 1994 and which mainly saw violence between the two main ethnic groups in the country: the Somali Issas and the Ethiopian origin Afars.

Sohonie says that after the war, 4 Mars was already no longer the majestic band it used to be but rather a folkloric troupe full of young people, and Djibouti’s new constitution had also got rid of political party music: “The 4 Mars they have today is not the same band, it is a totally different one.”

Libya was one of the last places where the old band performed just prior to the civil war, in 1991, when Muammar Gaddafi brought the whole troupe to Tripoli. The only other Arab country where the group also performed was Algeria in 1996, and that same year Libya brought them again for a second time.

Commitment to culture

Another contemporary band that Ostinato Records will feature in one of the two other chapters of the Djibouti Archives series is an Afar group called Dinkara.

Given that in Djibouti Somalis have largely controlled the political and cultural power since independence, most bands, such as 4 Mars, are Somali bands, and there were simply not as many Afar groups. With this new album, Sohonie says they aim to also showcase Djibouti’s Afar music.

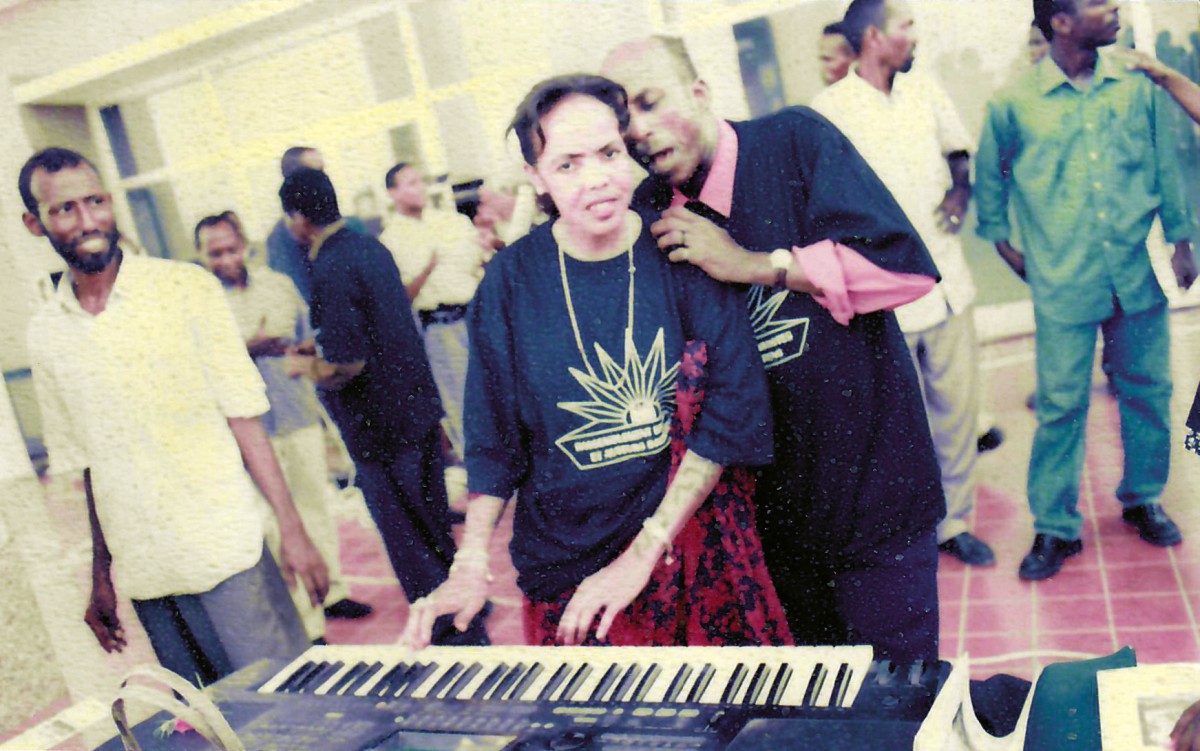

The last group that the label will feature in the series is called Sharaf, and Sohonie says that even though the band were also supported by the government, recorded in the national radio and performed in the national theatre, they were the only ones in Djibouti that could be considered private.

Sharaf was financed by a very wealthy Djiboutian businesswoman and it was a smaller group made up of seven to eight people that mainly performed in night clubs, so it captures the private scene that was also happening in the country at the time as 4 Mars.

The Djiboutian song has evolved, and is a reflection of the different currents that we undergo by force of the circumstances

– Rifki Abdoulkader, former deputy director of the Palais du Peuple

“In Djibouti, every ministry sort of had a band: the Ministry of Culture had a band, the national radio had a band, the political party had a band, the military had a band, the police had a band. We could have literally released 20 or 30 albums,” Sohonie says. Yet he said that Dinkara and Sharaf are “a different chapter of Djibouti’s music history”.

Djibouti today lacks what it had 40 years ago when many bands were financed, supported, and cared for by the government. The scars caused by a flux of money that has not been there for a long time are clear.

Yet, this commitment to culture is slowly coming back, especially as part of investments (as well as gifts, donations, and mutual deals) by the Chinese and Turkish governments, who both have military bases in the country. This way, Djibouti has been able to start renovating its iconic national theatre, rebuilding its archives, and training radio staff in analogue technology at Chinese universities. The government is also trying to build a new recording studio.

“Djibouti is a young country open to all foreign cultural currents. The Djiboutian song has evolved, and is a reflection of the different currents that we undergo by force of the circumstances,” says Abdoulkader.

In this light, Sohonie considers that the Djibouti Archives series could not have existed two or three decades ago because the country was still relatively closed off. Over recent years, however, Djibouti has been gradually opening up, and he notes that this process has also affected the attitudes of the country’s cultural leadership, which is now more open to starting projects, for example, that involve an archive that not long ago was off-limits to foreigners.

Now, Sohonie says, they want Djibouti’s culture to travel once again. “I think we are at the beginning stage of witnessing a huge revival, and I hope we can play a role in that.

“Djibouti needs the infrastructure and the resources, and it needs the globe’s attention. At this moment, it is not there, but it is coming … And what [Djibouti] still has is the will.”

Super Somali Sounds from the Gulf of Tadjoura is available from Ostinato Records, as part of their Djibouti Archives series

Source: Middle East Eye