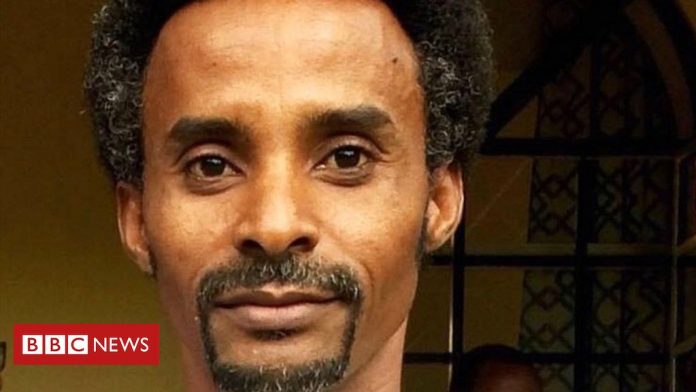

The BBC’s Girmay Gebru, who was one of several media workers detained recently in Mekelle, capital of Ethiopia’s conflict-hit Tigray region, describes what happened to him

I was arrested on the evening of my birthday.

I thought the soldiers, armed with rifles, were looking for someone else when they surrounded the coffee house where I was having my usual catch-up with my friends on Monday.

One officer came in and told everyone to relax and we carried on chatting. But just a few minutes later we were approached by two plain-clothed intelligence agents.

“Who are you?” one of them shouted impatiently.

“Tell us your names!”

“I am Girmay Gebru,” I said.

Slapped in the face

“Yes, you are the one we want.” And I was taken outside along with my five friends.

Then, in front of lots of curious onlookers, after I had handed over both my national and BBC ID cards, one of the intelligence agents slapped me round the face.

A soldier intervened and told him to stop and I was bundled into a patrol vehicle.

Everything was happening so quickly that we did not have time to ask why we were being held.

The conflict in Tigray

- Fighting erupted on 4 November 2020

- Ethiopia’s government launched an offensive to oust local party the Tigray People’s Liberation Front after its fighters captured federal military bases

- Tens of thousands have fled into Sudan (photo above)

- The internet and phone lines were cut and journalists were unable to report from the region

- Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed said the war was over at the end of November but fighting has continued

- There are concerns over human rights violations as well as the humanitarian situation

Even once we had arrived at a military base in the city there was no explanation.

But one of the people from intelligence told me: “Girmay, we are the government and we know what you are doing every day – what you are talking about, what messages you are sending. We know what you eat for breakfast, lunch and dinner.”

“Tell me what I’ve been doing,” I responded. “Tell me what I’ve been sending.”

Since the conflict began last November, I have not been filing stories for the BBC as I was told to look after my own safety first.

“It is you to tell me what you’ve been saying and thinking. You are going to tell me later,” he said.

Single phone call

This was not an interrogation but just a warning.

Our phones had been taken but a military official gave them back to us to make one call.

My wife was concerned when I told her what had happened but I said that I was fine and that she should not worry.

We were treated relatively well at the base, but the six of us had to sleep on the floor of a room and were given a plastic bottle each to use as a toilet.

Most of us were in shock and nervous about what was going to happen next. I couldn’t sleep.

In the morning, the intelligence agents said they wanted to search my house to get my laptop and would take that and my phone and get all the data from them. It turned out they never did search my home.

Smell of a septic tank

They also wanted to interrogate me as all the information they wanted was in my mind, they told me.

But still they did not say why we were being held.

I was confident that I had done nothing wrong.

“I am a journalist. I am a free person and you can ask me anything,” I said.

But I was not questioned. Instead, on Tuesday morning we were driven to a federal police station in the middle of Mekelle to be held there.

The conditions there were a lot worse.

I was put into a small cell that had no beds and measured about 2.5m by 3m with 13 others. It was very hot and the bad smell from a nearby septic tank made things worse.

‘I gave face masks to cellmates’

We were again given a bottle in case we needed to go to the toilet in the middle of the night. But I was so worried about needing to use it that the only food I ate was one orange.

Someone on my right-hand side was coughing and I was nervous about catching coronavirus. Luckily some friends of mine had heard where I was being held and managed to provide some face masks and sanitiser which I distributed to the other inmates.

Early on Wednesday morning a police officer came and told me to collect my things, saying that I could go home.

But there was no explanation as to why I was detained, though I know the BBC has asked the Ethiopian government what was behind the arrests.

My wife, my mother and my children were all at home when I got back and there were tears of happiness.

The thing that had worried me the most was getting sick in the cell in the police station. Now I feel relieved and hope to get some rest.

Source: BBC