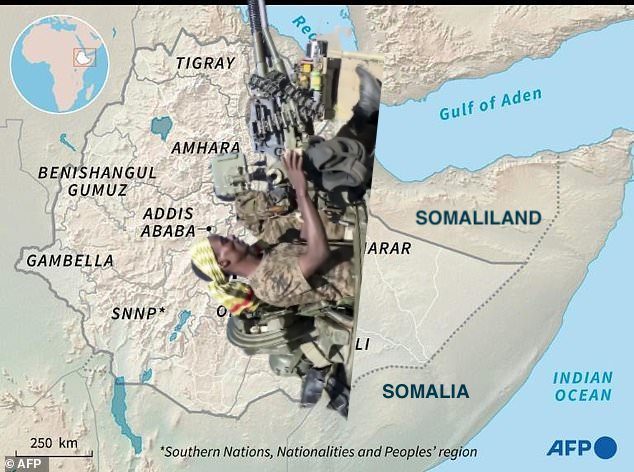

As conflicts rapidly unfold in Ethiopia, Sudan, Somalia and Yemen, the US, UK and European states are being sidelined

An even bigger fear is the break-up of Ethiopia itself in a Libyan or Yugoslav-type implosion. The country comprises more than 80 ethnic groups, of which Abiy’s Oromo is the largest, followed by the Amhara. Ethnic Somalis and Tigrayans represent about 6% each in a population of about 110 million. Ethiopia’s federal governance structure was already under strain before this latest explosion.

While it’s easy to point the finger at Abiy, Tigray’s leadership – the Tigray People’s Liberation Front – is just as much at fault for allowing political rivalries to degenerate into violence. Tigrayans dominated Ethiopia’s politics in the decades following the 1991 overthrow of Mengistu Haile Mariam’s Soviet-backed Marxist dictatorship.

But after the death in 2012 of Meles Zenawi, an authoritarian leader who achieved impressive economic advances, the TPLF lost its grip on power. Since Abiy took over in 2018, Tigray’s leaders have complained of being marginalised and victimised. A lethal attack this month on a federal army base in Mekelle, Tigray’s capital, triggered the intervention.

The fighting has brought predictable US and EU calls for an immediate cessation amid concerns that Ethiopia’s democracy as well as its territorial integrity are at stake. Elections, already postponed due to the pandemic, are due next year. But neither side is listening. Such deafness reflects the west’s declining influence and neglect of the Horn of Africa. This is the geopolitical backdrop to the Tigray emergency.

Interviewed in Addis Ababa in 2008, Meles told me he welcomed British and other foreign assistance but spoke passionately about Ethiopians’ right to set their own path. “We believe democracy cannot be imposed from outside in any society… Each sovereign nation has to make its own decisions and have its own criteria as to how they govern themselves,” he said.

In rejecting outside calls to cease fire, Abiy likewise stresses self-determination. He argues he is trying to build a shared national identity and common citizenship transcending the ethnic politics which, his supporters say, have held Ethiopia back. Abiy’s critics say this is shorthand for a new dictatorship of the centre.

If Abiy’s approach is proven wrong, the mistake will be his own. Analysts suggest the offensive is unlikely to bring the swift victory he predicts, partly because the national army comprises many Tigrayans and other minorities that could follow the TPLF’s example. The longer it goes on, the more probable that instability will spread within Ethiopia and beyond its borders.

The Amhara region adjacent to Tigray was reportedly bombed last week. Neighbouring Eritrea has also come under fire. Its president, the reclusive dictator Isaias Afwerki, is said to be backing Addis Ababa out of enmity for the Tigrayans who led a war against Eritrea that took 20 years to settle. This was the peace-making feat that helped win Abiy his Nobel prize.

Sudan, to the west, only now emerging from the turmoil that followed last year’s revolution, has meanwhile become the unhappy recipient of tens of thousands of fleeing refugees. The UN warned last week of a “full-scale humanitarian crisis”. For its part, South Sudan is in a state of permanent upheaval. Both countries might easily be tipped into renewed chaos.

Yet perhaps the biggest regional concern is Somalia, to the east, where an Islamist insurgency, grinding poverty and warring factions have long rendered the country almost ungovernable. Meles repeatedly warned of an Islamist threat to the Horn of Africa. In 2007 he controversially sent 10,000 Ethiopian troops to crush what he termed “Somalia’s Taliban”.

Ethiopian forces are still there. But now 3,000 soldiers are reportedly being withdrawn to join the Tigray offensive. Worries about a consequent power vacuum that could be filled by the Islamist group, al-Shabaab, or Islamic State, which is also present, have been compounded by Donald Trump’s sudden decision to reduce US military involvement.

Trump’s move has nothing to do with a careful evaluation of current threat levels or Somalis’ best interests and everything to do with securing his America First legacy. Although US special forces will remain in Kenya and Djibouti, 700 American soldiers conducting counter-terrorism missions and training inside Somalia are expected to be recalled.

Analysts warn the withdrawals could jeopardise elections due in Somalia next year, viewed as a vital step towards normality, while boosting al-Shabaab. The group already controls large rural areas. It frequently attacks security and civilian targets in Somalia and Kenya despite US-led drone strikes and raids. Six people died last week when a suicide bomber blew himself up in a Mogadishu restaurant.

Reduced American commitment may accelerate another worrying trend: an ongoing competition among Gulf states for strategic influence and resources across the Horn. Fierce rivals Qatar and the UAE have interests in Somalia and Eritrea. Turkey has also increased its involvement in line with its post-Arab Spring interventions in Libya and Syria. It recently donated armoured personnel carriers to the Somali government. Meanwhile, Russia is planning a naval base at Port Sudan.

As events rapidly unfold in Ethiopia, Sudan, Somalia and in war-torn Yemen, across the Gulf of Aden, the US, UK and European states are increasingly sidelined. They seem able to tolerate any amount of human suffering at a distance. But if region-wide turmoil increases refugee and migrant outflows and extends the reach of the terrorists, they may come to rue their role as passive spectators.

Source” The Guardian