Fighting between the government of Nobel Peace Prize winning Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and Tigrayan nationalists in the north could extend an evolving arc of crisis.

Ethiopia, an African darling of the international community, is sliding towards civil war as the coronavirus pandemic hardens ethnic fault lines. The consequences of prolonged hostilities could echo across East Africa, the Middle East and Europe.

Fighting between the government of Nobel Peace Prize winning Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and Tigrayan nationalists in the north could extend an evolving arc of crisis that stretches from the Azerbaijani-Armenian conflict in the Caucasus, civil wars in Syria and Libya, and mounting tension in the Eastern Mediterranean into the strategic Horn of Africa.

It would also cast a long shadow over hopes that a two-year old peace agreement with neighbouring Eritrea that earned Mr. Ahmed the Nobel prize would allow Ethiopia to tackle its economic problems and ethnic divisions.

Finally, it would raise the spectre of renewed famine in a country that Mr. Ahmed was successfully positioning as a model of African economic development and growth.

he rising tensions come as Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan failed to agree on a new negotiating approach to resolve their years-long dispute over a controversial dam that Ethiopia is building on the Blue Nile River.

US President Donald Trump recently warned that downstream Egypt could end up “blowing up” the project, which Cairo has called an existential threat.

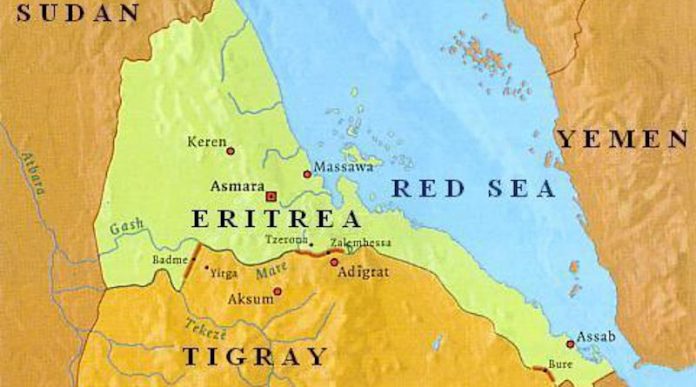

Fears of a protracted violent confrontation heightened after the government this week mobilized its armed forces, one of the region’s most powerful and battle-hardened militaries, to quell an alleged uprising in Tigray that threatened to split one of its key military units stationed along the region’s strategic border with Eritrea.

Tension between Tigray and the government in the Ethiopian capital of Addis Ababa has been mounting since Mr. Ahmet earlier this year diverted financial allocations intended to combat a biblical scale locust plague in the north to confront the coronavirus pandemic.

The tension was further fuelled by a Tigrayan rejection of a government request to postpone regional elections because of the pandemic and Mr. Ahmed’s declaration of a six-month state of emergency. Tigrayans saw the moves as dashing their hopes for a greater role in the central government.

Tigrayans charge that reports of earlier Ethiopian military activity along the border with Somalia suggest that Mr. Ahmed was planning all along to curtail rather than further empower the country’s Tigrayan minority.

Although only five percent of the population, Tigrayans have been prominent in Ethiopia’s power structure since the demise in 1991 of Mengistu Haile Mariam, who ruled the country with an iron fist. They assert, however, that Mr. Ahmed has dismissed a number of Tigrayan executives and sidelined businessmen in the past two years under the cover of a crackdown on corruption.

Like Turkey in the Caucasus, the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa, Mr. Ahmed may be seeing a window of opportunity at a moment that the United States is focused on its cliff hanger presidential election, leaving the US African Command with no clear direction from Washington on how to respond to the escalating tension in the Horn of Africa.

Escalation of the conflict in Tigray could threaten efforts to solidify the Ethiopian-Eritrean peace process; persuade Eritrean leader Isaias Afwerki, who has no love lost for Tigray, to exploit the dispute to strengthen his regional ambitions; and draw in external powers like Turkey, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar, who are competing for influence in the Horn.

The conflict further raises the spectre of ethnic tension elsewhere in Ethiopia, a federation of ethnically defined autonomous regions against the backdrop in recent months of skirmishes with and assassinations of ethnic Amhara, violence against Tigrayans in Addis Ababa, and clashes between Somalis and Afar in which dozens were reportedly injured and killed.

Military conflict in Tigray could also accelerate the flow of Eritrean migrants to Europe who already account for a significant portion of Africans seeking better prospects in the European Union.

A Balkanization of Ethiopia in a part of the world where the future of war-ravaged Yemen as a unified state is in doubt would remove the East African state as the linchpin with the Middle East and create fertile ground for operations by militant groups.

“Given Tigray’s relatively strong security position, the conflict may well be protracted and disastrous. (A war could) seriously strain an Ethiopian state already buffeted by multiple grave political challenges and could send shock waves into the Horn of Africa region and beyond,” warned William Davison, a senior analyst at the International Crisis Group.

By James M. Dorsey and Alessandro Arduino

- Dr. James M. Dorsey is an award-winning journalist and a senior fellow at Nanyang Technological University’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore and the National University of Singapore’s Middle East Institute.

- Dr. Alessandro Arduino is principal research fellow at the Middle East Institute of the National University of Singapore.

Source: Eurasiareview