China has given billions of dollars in loans to developing countries but now, as COVID-19 has increased the pace of record global debt levels, countries could be at risk of defaulting and China’s carefully cultivated relationships could be about to unravel.

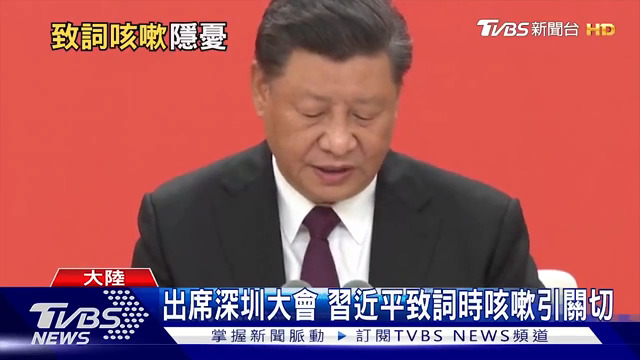

In 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced the launch of the “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI), an ambitious multi-billion project dubbed the Chinese Marshall Plan, which China says is to improve economic connectivity and cooperation across the globe.

Consisting of overland corridors and maritime shipping lanes, the scheme involves 71 countries and half of the world’s population. China says the initiative is an economic stimulus package, designed to help state-owned businesses in what it sees as a win-win situation. Critics have accused it of being a scheme with the aim of creating a Chinese-centered order.

Should any country default, it is feared that a similar situation could arise to the one in Sri Lanka, where the government was unable to service debt on the port. It was then leased by the government to Chinese firms on a 99-year lease. The U.S. has expressed concern that the port could be used by China as a naval base.

The Trump administration has repeatedly warned African nations that accepting Chinese loans could result in them losing control over strategic assets too. It has warned that a strategic port in the tiny Horn of Africa nation of Djibouti could succumb to the same fate, a prospect the government there has denied.

Now, with the global economy struggling with the fallout from COVID-19, those worries about defaulting are more real than ever. Yet is there any truth in the claims that China deliberately traps poorer countries into debt and should the rest of the world, including the U.S. as well as small and poorer countries be worried?

“Debt trap diplomacy is one form of financial pressure or coercion, but not the only form employed by China to accumulate influence, position, military access and power around the globe,” Rick Fisher, senior fellow at U.S. think-tank International Assessment and Strategy Center, tells Newsweek. “China’s goal is a revival of its Middle Kingdom style of global hegemony, in which Beijing eventually has the dominant say in a country’s prosperity and security.”

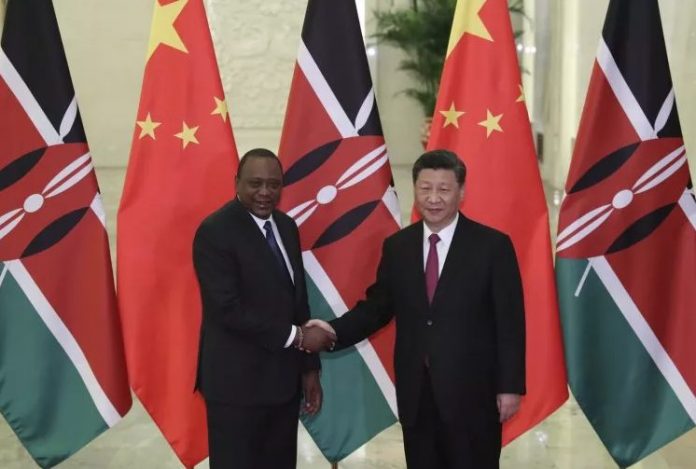

China has been the dominant trading partner with Africa and established the China Africa Defense and Security Forum in 2018.

“This group meets in China, is organized by the People’s Liberation Army and most African nations are members,” Fisher says. “From here, China will advance military relationships, that in coordination with economic and political inducements, lead to Chinese military access. So it is not just debt traps, they are just one tool in a far wider array of political, economic and military stratagems.”

Zambia has just issued a stark warning that it is about to default on debt to Chinese creditors, with China accounting for roughly a quarter of the country’s $12 billion of external debt. Kenya has also said that it wishes to renegotiate its $4.5 billion loan agreement with China.

Kimani Ichung’wa, chairman of Kenya’s Parliamentary Budget and Appropriate Committee, told The EastAfrican: “It is very easy to resolve this issue of loan repayment by just sitting down with the Chinese and telling them we made a mistake. We owe you all this money but you are also demanding so much from us in terms of repayment. This is a debt. Look, our economy is beaten and we are not able to pay. We are not saying the debt is not there, but we simply want to renegotiate what we owe you and the terms of payment.”

While China has committed to debt relief for 77 countries including Kenya under a recent G20 agreement to help poor and developing states during the pandemic, Kenya has already said it would not seek debt relief fearing it could harm its ability to tap capital markets.

Beijing is reported to have balked at demands for future debt write-offs for countries and with China’s failure to fully participate in agreements with all of its state-owned institutions, means that during a meeting with the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank urged parties to “hope for the best and prepare for the worst.” A solution is yet to be worked out between China and Kenya. In 2015, the China-Africa Research Initiative (CARI) at John Hopkins University identified 17 African countries which were considered to have risky debt exposure to China, and were potentially unable to repay their loans.

With the pandemic pushing poor and developing countries further into debt, there are concerns that China’s debt leveraging over such countries is going to increase. While China has canceled interest-free loans to Africa, according to researchers at Johns Hopkins University, interest-free loans account for less than 5 percent of Africa’s total debt to the country.* Countries such as Kenya and Zambia say further help is still needed.

Matters are complicated further by the fact that the debt African countries have incurred is not only with Chinese state-owned companies but also with private Chinese companies operating on the continent. Even if an agreement between China’s government and recipient countries can be agreed upon, researchers at Johns Hopkins University have identified more than thirty banks and companies with loans in Africa, some of them made at commercial rates, who still need to be negotiated with.

So far, the G20 has simply asked private companies to get on board with debt relief efforts, with the World Bank calling on China to put pressure on domestic creditors. Yet not everybody is convinced that China engages in debt trap diplomacy and will seize assets should countries default.

“It’s complete nonsense, it is a myth,” Dr. Lee Jones, Reader in International Politics at Queen Mary, University of London and China foreign policy expert, tells Newsweek. “The idea that China is deliberately ensnaring developing countries in debt knowing that they will fall into debt distress and knowing that will allow China to seize the projects built there is just utter nonsense. There’s not a shred of evidence for it all.

“It’s a myth that’s been propagated by Indian think tanks and picked up in the U.S. for purely political reasons, it just isn’t happening. Is China lending money to developing countries for projects that are perhaps not very good and maybe won’t make enough money to repay them? Absolutely. But it’s not doing that because it is trying to trap developing countries. It’s doing that because it needs to get contracts for state-owned enterprises, it’s got a lot of surplus capital it wants to get rid of. It’s trying to curry favor in developing countries.

“The idea is that China came up with these projects and pushed them on these countries and lured them into debt so that when they fell over China will be able to seize these assets which is totally not true. These projects were proposed to China by the governments of those countries and in fact that’s how Chinese development financing works, its recipients must ask China for the projects and they must agree to any projects that happen on their territory. They wouldn’t agree if they didn’t think it was a good idea.”

China is pushing ahead with its Belt and Road Initiative, with the country’s foreign minister Wang Yi saying that the country’s interest in the initiative remained “unchanged”. With trade increasing between China and those countries, even in the pandemic, what happens to the mounting debt will be watched closely. With half the world’s population directly involved in some way, it’s easy to see why.

By Basir Mahmood

Source: Newsweek

*Study methodology and notes

- The research by Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies used data on Chinese loan commitments from the SAIS China Africa Research Initiative and the World Bank, and data on African borrowing and debt levels from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund’s International Debt Statistics.