Traders fled from the expiring May U.S. oil futures contract in a frenzy on Monday, sending the contract into negative territory for the first time in history, as barely any buyers are willing to take delivery of oil barrels because there is no place to put the crude.

The May contract for U.S. West Texas intermediate crude oil plunged to below zero for the first time in history, settling on the day at minus $37.63 a barrel, a decline of some 305%, or $55.90 a barrel. Prices set a low of negative $40.32.

Brent crude oil, the international standard price most often cited as the going price of a barrel of oil, also fell, down 5.27% to $26.60 per barrel.

With demand down 30% worldwide due to the coronavirus pandemic, and the main U.S. storage hub in Cushing, Oklahoma, expected to fill up in a matter of weeks, very few want to be stuck with oil barrels that they have to take delivery on at some point during May.

“The people who are long are desperate to get out,” said Phil Verleger, a veteran oil economist and independent consultant. “If you don’t have storage, you have to get out.”

Major oil-producing nations have agreed to cut output, and global oil companies are trimming production, but those cuts will not come quickly enough to avoid a massive clog. The excess from overseas producers can be stored in more places, including aboard tankers at sea. But that’s not the case with domestic oil produced in the U.S. and Canada.

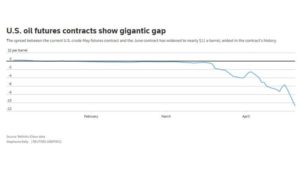

The difference between the expiring May U.S. West Texas Intermediate crude contract and the coming June contract widened to a record at more than $60 a barrel and settled at $51.90. That yawning gap emerged because owning the May contract when it expires on Tuesday means that buyer is obligated to take those barrels, which few want to do.

“For many investors or people using these contracts for hedging this is really a big pain,” said Edward Moya, market analyst at OANDA in New York. “There’s no place to put it — we’re running out of space to store oil.”

The June contract ended down 16% to $20.43 a barrel.

When a futures contract expires, traders must decide whether to take delivery or roll their positions into an upcoming contract. Usually this process is relatively uncomplicated, but the May contract’s decline reflects worries that too much supply could hit the markets, with shipments out of OPEC nations like Saudi Arabia booked in March set to cause a glut.

Available storage space is dropping fast at the Cushing, Oklahoma, hub, where physical delivery of U.S. oil barrels bought in the futures market takes place. Four weeks ago, the storage hub was half full — now it is 69% full, according to U.S. Energy Department data.

“It’s clear that Cushing is going to fill, and it will stay full for the next several months,” said Andy Lipow of Lipow Oil Associates. “Because producers have been lagging in their production cuts, we’re seeing an overwhelming amount of crude oil looking for a place to go around the world.”

Crude stockpiles at Cushing rose 9% in the week to April 17, totaling around 61 million barrels, market analysts said, citing a Monday report from Genscape.

The world’s major oil producers agreed to cut production by 9.7 million bpd in an attempt to get world supply under control as demand slumps, but those cuts do not begin until May. Saudi Arabia is ramping up deliveries of oil, including big shipments to the United States.

Worldwide oil consumption is roughly 100 million barrels a day, and supply generally stays in line with that. But consumption is down about 30% globally, and the cuts so far are far less.

U.S. exchange-traded funds are also playing a role in the action, analysts said. The U.S. Oil Fund LP the largest crude oil ETF, said on Thursday that it would start moving some of its assets into later-dated contracts earlier in the life of the monthly contract.

Source: Reuters