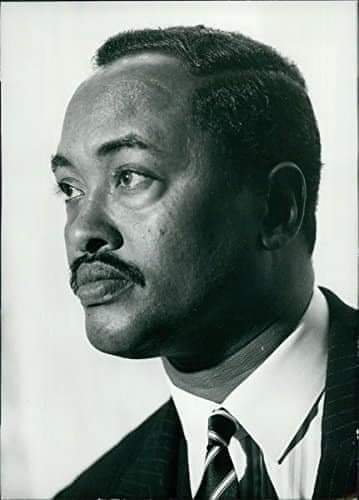

Ahmed Haji Dualeh Abdalla, affectionately known as Ahmedkeyse, died peacefully on the early hours of Wednesday 8th of January 2020 in Tuscon, Arizona. His death would naturally be mourned by his immediate family, relatives and friends, and indeed, many in the Somalia Communities all over the world, who are aware of the pivotal role he had played in the nationalist struggle for independence and unity government in which it culminated.

Even though we are all saddened by his death, Ahmedkeyse’s life was by any standards gloriously full, dignified, and crowned with unsurpassed accomplishments that few others could ever espouse to match. He was truly a pioneer in so many walks of life, who not only broke records but indeed had the privilege to set them himself.

Ahmedkeyse was born in Burao in 1928. His father Haji Dualeh Abdalla was a genuinely pious man and religious scholar, who worked as a Magistrate and a Qadi in the Islamic courts system that administered Sharia Law British Somaliland. His mother, Xalimo Abdi, died when he was just seven years old and he, and his two siblings came under the care of his kind and generous stepmother lady Sharifo.

Ahmed Kaise was one of the first of Somalis to ever manage to attend school, which he started in Berbera in 1938. However, this was interrupted by the second world war and the Italian occupation of Somaliland. He and his family were evacuated to the safety of Aden.

On his return few years later, he joined the newly-formed intermediate school in Sheikh administered by demobbed British army officers with innate belief in the ethos of the English public school system (elsewhere known as private schools for the elite), which prioritised academic excellence in key core subjects on the one hand, and physical fitness, sport in general and athletics in particular.

Ahmedkeyse’s contemporaries included two future presidents of Somaliland: Abdirahman Ahmed Ali and Mohamed Ibrahim Egal.

In 1948 Ahmedkeyse and three of his colleagues won a free scholarship to the prestigious Hantoub college in Khartoum, Sudan. On passing the exams four years later, they went to England for a scholarship. Ahmed enrolled in the University Keel, in northern England. He graduated in the summer of 1956 with a First-Class Honours Degree in Economics, and could therefore proudly claim to be the first university graduate from Somaliland.

He returned to Somaliland in the same year and was appointed as Assistant District Commissioner – the highest ever post for a Somalia. However, when the authorities discovered his clandestine work in the nationalist liberation movement, he was transferred to Lascanod, the capital of the eastern region considered to be a hostile territory beset with violent clan antagonism. Contrary to expectations Ahmed’s stay proofed a spectacular success, for he managed, through clever negotiation, to end the inter-clan wars that bedevilled the region and thus became a national hero. In effect, he undermined the divide-and-rule politics of the colonial authorities, which in fact the cause of very inter-clan wars on which they blamed the Somalis. It was no accident that they identified him as a ‘trouble maker’.

While in Las Anond, Ahmed Kaise had a physical confrontation with an arrogant racist British official. Consequently, he was recalled back to Hargeisa under an armed escort and was expected to be officially charged with sedition (a heavy charge indeed) next morning. However, with an hour of his arrival, he took a taxi to the border town of Wajale, bluffed his way past the border guards, crossed into Ethiopia, applied for political asylum that was readily accepted by Emperor Haile Salassie. After assessing his qualification, the Ethiopians offered him a senior post at the Ministry of Interior, presided by the second most powerful aristocrat in Addis, and son the son-in-law of the Emperor.

In early 1959 Ahmed Kaise left Ethiopia for Somaliland. By then the British were already a spent force. The real contest was between three political: SNL, SDU and NUF. The first two were practically allies united by their core policy of a speedy departure of the British and an immediate unification with Italian Somalia as a prelude to Greater Somalia. The position of the NUF, though somewhat ambiguous, amounted to a desire to keep the status quo for another ten years to enable the British to prepare Somaliland as a viable state through a concerted program of investment in education, skills training and in the productive sectors of the economy.

Somali parties are invariably clan orientated, and while Ahmed Kaise was in clan terms more akin to the NUF, he bravely decided to put national interest before clan and thus joined the SNL. As a principled operator, from a highly respected family whose unstinting support he had, and a great orator, he soon became one of the leading lights of the party.

In the ensuing general election of 1960, the coalition of SNL and USP won a landslide victory taking a staggering 32 seats of 33 in parliament. Soon after Somaliland declared its independence in June 1960, and formed its first government headed by Mr. Egal as the prime minister, while Ahmed Kaise took Agriculture; Haji Ibrahim Noor education; and Ali Grad Jama became Health Minister. Four days later the unification of Somalia and Somaliland took place and the new state of Somali Republic was born in July 1st, 1960.

The post of president was given temporarily to Adan Abdulla Osman for a period of a year, after which the parliament would hold a presidential election for a six-year term. Abdirashid Ali Sharmarki became prime minister. Ahmed Kaise kept his portfolio of Minister of Agriculture and got work immediately with reforming zeal.

Ahmed remained in cabinet for two years, and of the many political agenda, he advocated, three stand out. Firstly, he forcibly ended the feudal system that existed in Agriculture whereby Italian and influential Somali politicians had a monopoly on the lucrative export of banana to Italy. Instead, he enfranchised the poor peasant farmers who witnessed with awe the transformation of their circumstance: from downtrodden, abjectly poor peasants to landlords in their own right, with an undreamed income to match. On the side of the agricultural equation, powerful people found difficult to accept the loss of a sizable and easy income which they have enjoyed so long, and have become implacable enemies of the minister responsible for their perceived injustice.

The other policy advocated by Ahmedkeyse and two of his ministerial colleagues was the establishment of a closer relationship with the Soviet Union, especially in the military and security arenas. When prime minister Abdirashid came back empty-handed from a trip to the USA, Ahmedkeyse, Ali Garad and Sh. Ali Jimcale urged him to try the other superpower instead. And although the majority of the cabinet were opposed, the prime minister heeded their advice, arranged a trip to Moscow, with the three ministries as members of the delegation. Contrary to expectations, the trip was immensely successful, and the delegation returned triumphantly with a sizable package of military and economic aid unmatchable by anything the West could offer.

Although the critics of the policy were for moment muted, the success of trip created a yet more powerful coalition of enemies that included the American Embassy, the Italian lobby and their allies in parliament and elsewhere. And when proposed that the Somali Republic should consider joining the British Commonwealth, the Italian lobby was up in arms. The rationale of the policy was to improve the diplomatic relationship with Britain at a time when the Mau Mau rebellion. The British were at time sympathetic, indeed well-disposed to our territorial claim to the North Frontier District (NFD) largely inhabited by ethnic Somalis. A success here would have certainly bolstered our claim against Ethiopia and French Somaliland (Djibouti) as it was then known.

An unholy alliance of foreign powers, parliamentarians and influential businessmen lobbied for the removal of Ahmed Kaise from the cabinet as a condition for their support. To press they staged a vote of confidence in parliament, which the government actually lost thereby forcing the prime minister to seek a second vote of confidence, or resign altogether. Prime Abdirashid was reluctant to lose one of his most able and honest ministers, and yet his premiership was at stake. Ahmed Kayse, appreciative always of the unstinting backing he got from the prime minister, came to the rescue by tendering his own resignation, not only from the government but the parliament as well.

Ahmed Kayse left parliament in the summer of ’62, and while the parliamentary politics of Somalia took a downward slide that would end in its demise within seven years, Ahmed Kayse became a career diplomate as an ambassador to various weighty missions. His first post was in Germany, and since the relationship between Somalia and the Federal Government were on the whole rather good, his task there was not only to keep it just that but to also elicit as much aid and technical assistance as possible. Among the projects which Ahmed lobbied for was a well-funded and equipped technical institute in Burao. The Germans accepted the idea of the institute but chose Xamar as the destination where their ‘golden gift’ could shine brightly among the glitter of the capital city rather than a provincial backwater. Being an ambassador with clout, Ahmed categorically rejected their suggestion on the grounds that it is in the national interest to disperse developmental projects all over the country rather than concentrate them in the capital, which in any case has so many other facilities and advantages that the regions lack. Ahmed’s ideas were certainly quite novel and, in many ways, ahead of their time so much so that the Germans rejected them as utopian. The ensuing deadlock was broken by the prime minister Abdirashid who back Ahmed while on a state visit to Germany. Thus, Burao got the only developmental project from a Somali government, past or present.

In 1964 Ahmedkeyse was transferred as an ambassador to Cairo. The relationship between the Somali and Egyptian government was rather bad because Nasser suspected that President Adan supported Nasser’s nemeses, the Saudi King. Ahmed managed to reassure that that was not the case and that in fact Somalia needs and peruses an even-handed policy.

In 1968 Ahmed Kaise was transferred to Aden and remained there until May 1970 when the new military regime identified him as the best man to manage a rather frosty relationship with a British government suspicious of the regime’s close ties with the Soviet Union. Though never easy, he succeeded to put the relationship in even keel.

London was Ahmed’s last ambassadorial post. He stayed there until 1975. In 1976 he became a director of the newly formed Islamic Bank in Jedda and stayed there for three years. On leaving the bank, he joined the private sector and became a director of Boqshan group of companies where he stayed until 2003 when he immigrated to Tuscon, Arizona.

While in Jedda, Somali politics took a different turn and opponents of Siad’s regime organised an armed struggle against him. During this time Ahmed was allotted the role of an elder statesman. And although he supported their broad aims, he urged the two opposition groups to form a united front as a tactical and strategical policy against a shared enemy. Unfortunately, that advice was never heeded, and once Siyad’s regime fell, the was no credible force to take. Instead, the country fragmented; Somaliland broke away and many parts of Somalia descended into anarchy and lawlessness.

To his last breath, AhmedKeyse believed in the unity of a Greater Somalia and Somalis everywhere. It remained for him the essence of his life’s work, energy and existence. It was always what his struggle was about. To the end he never lost hope; believed that Somalis would one day come to their senses and be once more a united, powerful and purposeful country. Our faith demands the fulfilment of this dream; and so does our history, culture and if nothing else self-interest. United we prosper, divided we die.

Ahmed Haji is certainly a key figure in the history of Somaliland and Somalia. His death merits not only sadness but a celebration for the contributions and sacrifices he made his country and his people.

Ahmed Kaise is survived by his wife Qamar and four children: Harbi, Khadra, Nura and Ayanle.

By Abdirahman Abdulkadir