Ethiopia’s political opening under Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has won well-deserved accolades but also uncorked dangerous centrifugal forces, among them ethnic strife. With international partners’ diplomatic and financial support, the government should proceed more cautiously – and consultatively – with reforms that could exacerbate tensions.

What’s new? Clashes in October 2019 in Oromia, Ethiopia’s most populous region, left scores of people dead. They mark the latest explosion of ethnic strife that has killed hundreds and displaced millions across the country over the past year and half.

What’s new? Clashes in October 2019 in Oromia, Ethiopia’s most populous region, left scores of people dead. They mark the latest explosion of ethnic strife that has killed hundreds and displaced millions across the country over the past year and half.

Why did it happen? Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has taken important steps to move the country toward more open politics. But his efforts to dismantle the old order have weakened the Ethiopian state and given new energy to ethno-nationalism. Hostility among the leaders of Ethiopia’s most powerful regions has soared.

Why does it matter? Such tensions could derail Ethiopia’s transition. Meanwhile, reforms Abiy is making to the country’s powerful but factious ruling coalition anger opponents, who believe that they aim to undo Ethiopia’s ethnic federalist system, and could push the political temperature still higher. Elections in May 2020 could be divisive and violent.

What should be done? Abiy should step up efforts to mend divisions within and among Ethiopia’s regions and push all parties to avoid stoking tensions around the elections. International partners should press Ethiopian leaders to curb incendiary rhetoric and offer increased aid to protect the country from economic shocks that could aggravate political problems.

Executive Summary

Ethiopia’s transition has stirred hope at home and abroad but also unleashed dangerous and divisive forces. As Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s government has opened up the country’s politics, it has struggled to curb ethnic strife. Mass protests in late October in Oromia, Ethiopia’s most populous region, spiralled into bloodshed. Clashes over the past eighteen months have killed hundreds, displaced millions and fuelled tensions among leaders of Ethiopia’s most potent regions. Abiy’s remake of the ruling coalition, which has monopolised power for almost three decades, risks further deepening the divides ahead of the elections scheduled for May 2020. The premier and his allies should move cautiously with those reforms, step up efforts to cool tensions among Oromo factions and between Amhara and Tigray regional leaders, who are embroiled in an especially acrimonious dispute, and, if conditions deteriorate further, consider delaying next year’s vote. External actors should call on all Ethiopian leaders to temper incendiary rhetoric and offer increased financial aid for a multi-year transition.

First, the good news. Since becoming premier in early 2018, after more than three years of deadly anti-government protests, Prime Minister Abiy has taken a series of steps worthy of acclaim. He has embarked on an historic rapprochement with Eritrea. He has extended his predecessor Hailemariam Desalegn’s policies of releasing political prisoners and inviting home exiled dissidents and insurgents. He has appointed former activists to strengthen institutions like the electoral board and accelerated the reform of an indebted state-led economy. His actions have won him both domestic and foreign praise, culminating in the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize. But Abiy’s moves to dismantle the old order have weakened the Ethiopian state. They have given new energy to the ethno-nationalism that was already resurgent during the mass unrest that brought him to power. Elections scheduled for May 2020 could turn violent, as candidates compete for votes from within their ethnic groups.

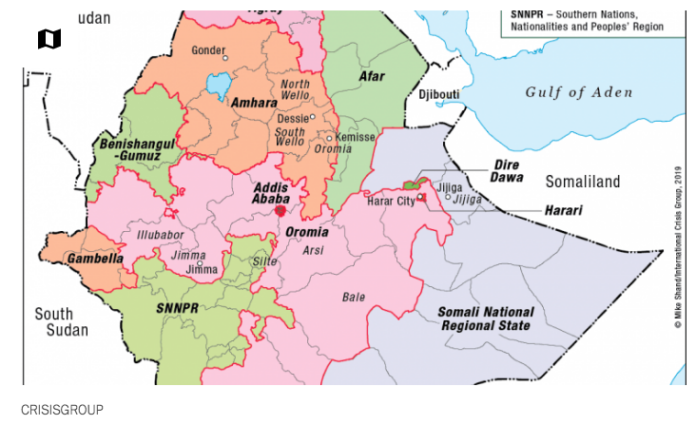

Four fault lines are especially perilous. The first cuts across Oromia, Abiy’s home state, where his rivals – and even some former allies – believe the premier should do more to advance the region’s interests. The second pits Oromo leaders against those of Amhara, Ethiopia’s second most populous state: they are at loggerheads over Oromia’s bid for greater influence, including over the capital Addis Ababa, which is multi-ethnic but surrounded by Oromia. The third relates to a bitter dispute between Amhara politicians and the formerly dominant Tigray minority that centres on two territories that the Amhara claim Tigray annexed in the early 1990s. The fourth involves Tigray leaders and Abiy’s government, with the former resenting the prime minister for what they perceive as his dismantling of a political system they constructed, and then dominated, and what they see as his lopsided targeting of Tigrayan leaders for past abuses. An uptick of attacks on churches and mosques across parts of the country suggests that rising interfaith tensions could add another layer of complexity.

Adding to tensions is an increasingly salient debate between supporters and opponents of the country’s ethnic federalist system, arguably Ethiopia’s main political battleground. The system, which was introduced in 1991 after the Tigray-led revolutionary government seized power, devolves authority to ethno-linguistically defined regions, while divvying up central power among those regions’ ruling parties. While support and opposition to the system is partly defined by who stands to win or lose from its dismantling, both sides marshal strong arguments. Proponents point to the bloody pre-1991 history of coercive central rule and argue that the system protects group rights in a diverse country formed through conquest and assimilation. Detractors – a significant, cross-ethnic constituency – argue that because the system structures the state along ethnic lines it undercuts national unity, fuels ethnic conflict and leaves minorities in regions dominated by major ethnic groups vulnerable. It is past time, they say, to turn the page on the ethnic politics that for too long have defined and divided the nation.

Prime Minister Abiy’s recent changes to the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), the coalition that has ruled for some three decades, play into this debate. Until late November, the EPRDF comprised ruling parties from Oromia, Amhara and Tigray regions, as well as a fourth, the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ region. Already it was fraying, its dysfunction both reflecting and fuelling ethnic animosity. Abiy’s plan entails dissolving the four blocs and merging them, plus five parties that rule Ethiopia’s other regions, into a new party, the Prosperity Party. The premier aims to shore up national unity, strengthen his leadership and shift Ethiopia away from what many citizens see as a discredited system. His approach enjoys much support, including from Ethiopians who see it as a move away from ethnic politics. But it also risks further stressing a fragile state whose bureaucracy is entwined with the EPRDF from top to bottom. Tigray’s ruling party and Abiy’s Oromo rivals oppose the move, seeing it as a step toward ending ethnic federalism. Tigray leaders refuse to join the new party.

The prime minister has made laudable efforts to tread a middle ground and unite the country but faces acute dilemmas.

The prime minister has made laudable efforts to tread a middle ground and unite the country but faces acute dilemmas. Placating nationalists among his own Oromo, for example, would alienate other ethnic groups. Allowing Tigray to retain a say in national decision-making well above the region’s population share would frustrate other groups that resent its long rule at their expense. Moreover, while thus far Abiy has tried to keep on board both proponents and critics of ethnic federalism, his EPRDF merger and other centralising reforms move him more squarely into the camp of those opposing that system, meaning that he now needs to manage the fallout from those who fear its dismantling and the dilution of regions’ autonomy. At the same time, he cannot leave behind the strong constituency that wants to move away from ethnic politics and thus far has tended to give Abiy the benefit of the doubt. But the prime minister, his government and international partners can take some steps to lower the temperature:

- Abiy should press Tigray and Amhara leaders to intensify talks aimed at mending their relations. He should continue discussions with dissenting Oromo ruling party colleagues and the Oromo opposition, aiming to ensure that they litigate differences at the ballot box rather than through violence. He should continue to facilitate talks between Oromo and Amhara leaders and thus ease tensions that are increasingly shaded by ethnicity and religion and feed a sense of ferment in mixed urban areas across the country, including in the capital.

- The government might also make conciliatory gestures toward the Tigray, maybe even rethinking its prosecutions of Tigrayan former officials in favour of a broader transitional justice process. For their part, Tigray leaders should reconsider their rejection of the Administrative Boundaries and Identity Issues Commission, which was set up to resolve boundary disputes like that pitting Tigray against Amhara.

- Abiy and his allies should move carefully with the EPRDF reform and seek to mitigate, as best as they can, fears that it heralds the end of ethnic federalism. They should make clear that any formal review of Ethiopia’s constitution that takes place down the road will involve not only the ruling party but also opposition factions and activists. An inclusive process along these lines would also serve the interests of ethnic federalism’s opponents, particularly among civil society, who would have a seat at the table.

- The prime minister is set on May 2020 elections, fearing that delay would trigger questions about his government’s legitimacy. If the vote goes ahead as scheduled, he should convene a series of meetings involving key ruling and opposition parties, along with influential civil society representatives, well beforehand to discuss how to deter bloodshed before and after a ballot that he has promised will represent a break from the flawed elections of the past. But if risks of a divisive and violent election campaign increase, his government may have to seek support among all major parties for a postponement and some form of national dialogue aiming to resolve disputes over past abuses, power sharing, regional autonomy and territorial claims.

- Ethiopia’s international partners should adopt a stance more in tune with worrying trends on the ground. They should express public support for the transition but lobby behind closed doors for a careful approach to remaking the EPRDF and for all Ethiopian leaders to temper provocative language as much as possible. They could also suggest an election delay if the political and security crises do not cool in the months ahead. A multi-year package of financial aid could help strengthen weak institutions, support an economy also undergoing structural reform and reduce discontent among a restive and youthful population during a period of change.

Ethiopia’s transition may not yet hang from a precipice; indeed, it is still a source of hope for many in Ethiopia and abroad.

Ethiopia’s transition may not yet hang from a precipice; indeed, it is still a source of hope for many in Ethiopia and abroad. But signs are troubling enough to worry top and former officials. Among the most alarmist suggestions made by some observers is that the multinational federation could break apart as Yugoslavia did in the 1990s. This worry may be overstated, but Abiy nonetheless should err on the side of caution as he walks a tightrope of pushing through reforms while keeping powerful constituencies on board. He should redouble efforts to bring along all of Ethiopia’s peoples, facilitate further negotiations among sparring regional elites, take steps to ensure that the ruling party merger does not further destabilise the country and, for now, defer formal negotiations over Ethiopia’s constitution and the future of ethnic federalism.

I. Introduction

Between 23 and 26 October, mass protests and ethnic strife left at least 86 people dead in Oromia, Prime Minister Abiy’s home state and Ethiopia’s largest and most populous, in which some 37 million people reside. The latest unrest, coming only four months after rogue security forces assassinated the Ethiopian military’s chief of staff and the president of Amhara state, cast in even sharper relief the precariousness of the country’s mooted transition to a more open and democratic order. In a widening arc of flashpoints across Ethiopia, attackers, often propelled by ethno-nationalist forces, have killed hundreds over the past year and triggered the displacement of 3.5 million. The wave of insecurity has set many Ethiopians on edge. Since coming to power in April 2018, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s changes have come at dizzying pace. But they have also lifted the lid that Ethiopia’s previously strong, and often abusive, state security machine kept on social tensions. Warning signs are starting to flash red.

This report examines the most dangerous fault lines and explores options for dialling down tensions. It builds upon Crisis Group’s previous work on Ethiopia’s transition, one of the most closely watched on the continent. It is based on interviews with Ethiopian officials, activists, intellectuals and researchers as well as African and Western diplomats. Research took place during July, November and December 2019 in the capital Addis Ababa and Amhara, Tigray and the Southern Nations states.

II. Trouble in Oromia

The most recent bout of turmoil began on October 23 after Jawar Mohammed, a prominent Oromo activist and media owner, accused the government on Facebook of stripping him of his security detail in an attempt to facilitate his assassination. After the Facebook post, hundreds of protesters gathered outside Jawar’s home in the capital to defend him and thousands took to the streets across Oromia. Demonstrations in the region in 2015-2018 had taken place mostly in rural areas; this time, protests shook some of Oromia’s multi-ethnic towns and cities. They led to death and destruction as other groups rallied in response and confrontations triggered violence. Security forces shot ten protesters dead, while losing five from their own ranks. Oromo youth groups, or Qeerroo, played a major role in the bloodshed, in some cases instigating attacks against other groups, as well as fellow Oromos deemed to display insufficient ethnic solidarity, and in other instances retaliating after provocations.

The late October violence reflects an evolution of the grievances that brought hundreds of thousands of Oromo into the streets in anti-government protests that began in earnest in 2015.

Jawar is an influential but divisive figure who over the course of 2019 has become a vocal Abiy critic. For years, he ran the prominent Oromia Media Network from abroad and was among the dissidents whom the government welcomed home in 2018. He has a large Oromo following, reflecting his advocacy for greater influence for the community. Many Amhara and other non-Oromo, however, hold him responsible for inciting Qeerroo to attack minorities and destroy their property.

Jawar has long lobbied for greater Oromo heft in the federal government and played a vital role in coordinating the protests that helped bring Abiy to power. But his relations with the new prime minister, always uneasy, have taken a turn for the worse, as he has reproached Abiy for centralising power and for not doing enough for the Oromo since taking office. The day before the Facebook post, on 22 October, Abiy appeared to condemn Jawar in parliament when he cited irresponsible actions by “foreign media owners”.

The late October violence reflects an evolution of the grievances that brought hundreds of thousands of Oromo into the streets in anti-government protests that began in earnest in 2015. Then, demonstrators were angered by the government’s abuses, corruption and failure to tackle rising living costs, youth unemployment and other day-to-day concerns. Protests had ethnic undertones, giving voice to the Oromo’s longstanding opposition to the Tigray ruling party’s pre-eminence in the EPRDF and federal security apparatus. Activists drew from a narrative asserting that the Oromo were historically downtrodden, left without an equitable share of federal power and represented by an Oromo ruling party – formerly the Oromo People’s Democratic Organisation (OPDO) and then, until its recent dissolution, the Oromo Democratic Party (ODP) – that was subservient to the Tigray party, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). Some concerns were more specific: Oromo activists opposed government plans to develop areas on the outskirts of Addis Ababa, which the Oromia region encircles, as portending further displacement of Oromo farmers to the benefit of investors.

Although OPDO leaders faced the ire of Oromo protesters, many party officials also backed the demonstrations, hoping to increase their power within the EPRDF. They objected in particular to the Tigray ruling party’s equal vote in the ruling coalition’s decision-making bodies, despite the region’s smaller population, and to the Tigrayan grip on the security sector, including national intelligence agencies and the armed forces.

Despite euphoria among the Oromo at Abiy’s appointment, strife has continued in Oromia.

Despite euphoria among the Oromo at Abiy’s appointment, strife has continued in Oromia. Much has been linked to the August 2018 return of rebel Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) leaders to Ethiopia. The week of their arrival saw Qeerroo youth groups run riot through parts of the capital, including its outskirts in Oromia, in some cases attacking people of other ethnicities. While the OLF’s return appears to have been conditioned on its participation in democratic politics, ODP officials accuse it of continuing to foment armed rebellion. Since coming back to Ethiopia, the rebel movement, already fragmented, has split again. Dawud Ibsa, who led the group in its Eritrean exile, is seeking deals with Abiy’s party and other Oromo groups. Others, including some field commanders, are holding out, still skirmishing with the military in western Oromia.

Interfaith tensions add another layer of complexity. During the recent unrest, Orthodox Christian leaders reported mobs targeting their congregants and churches, while demonstrators also attacked a mosque in Adama city, in central Oromia. The violence follows similar attacks on places of worship over the past eighteen months.

These attacks led some to suspect that religious differences underlay much of the unrest. Some Oromo nationalists portray the Orthodox Christian church as part of the predominantly Amhara power structure under the old imperial regime, which they accuse of suppressing their identities and culture for centuries. Indeed, the targeting of Orthodox churches as a symbol of the old establishment is a problem not limited to Oromia: protesters attacked churches in the Somali region in August 2018 and in Southern Nations in July 2019. In turn, Jawar’s opponents brand him as an Islamist. Jawar supported an overwhelmingly peaceful civil resistance movement in 2011-2012 that rejected the government’s interference in Muslim affairs, but no evidence supports the accusation that he is pursuing an Islamist agenda. Responding to the October fighting, Abiy explicitly recognised its religious dimension, but in a positive way, praising “Muslims who protect churches from burning down and Christians who stand guard to prevent mosques from burning down”.

At bottom, Oromo activists, like Jawar, and opposition groups including the OLF have political and not religious goals: they want a share of federal power that matches Oromia’s demographic weight and protects their regional autonomy. They welcome the de facto influence Abiy’s premiership delivers for the Oromo but distrust his political agenda. Some also want Afaan Oromo, the Oromo mother tongue, to become a working language of the federal government (at present, all central government business is conducted in Amharic) and for the Oromia region to administer Addis Ababa. Several leaders in the Oromo ruling party, including Lemma Megersa, the influential defence minister and a former close ally of Abiy, may even back the activists’ more assertive agenda.

Opposition among the Oromo puts Abiy in a bind.

Opposition among the Oromo puts Abiy in a bind. On one hand, many non-Oromo accuse Abiy of favouring his own ethnic constituency, pointing to his alleged leniency in dealing with Oromo abuses, Jawar’s provocations and the OLF’s insurgency. Forming an alliance with or adopting policies to mollify Oromo opponents could pit Abiy against other groups in Ethiopia’s bitterly contested political landscape. On the other hand, many Oromo appear ready to take to the streets to protest what they see as Abiy’s failure to advance their interests, with demonstrations frequently descending into violence. Moreover, the former rebel movement, the OLF, though fractured, is still popular. An alliance among OLF factions, Jawar and other Oromo opposition leaders, which is already taking shape, could present Abiy’s ODP with serious electoral competition in Oromia, particularly if it can pull away top ODP politicians like Lemma. The outbreak of communal strife following the 22 October incident at Jawar’s residence demonstrates just how volatile Oromia’s politics are.

III. Widening Ethno-regional Fissures

The Oromia bloodshed follows other incidents of violence across the country over the past eighteen months. The four regions that have been run by the EPRDF’s member parties – Amhara, Tigray and Southern Nations, as well as Oromia – face the gravest challenges, showing how the ruling coalition’s travails lie at the core of Ethiopia’s instability. As intra-EPRDF competition increases, ethno-nationalist forces within the four parties are ascendant, in some cases propelled by hardline opposition and protest movements. Those forces have driven ethnic animosity, particularly among the Oromo, Amhara and Tigray, as well as violence that since the beginning of 2018 has led a huge number of Ethiopians – some 3.5 million, more than in any other country in the world in 2018 – to flee their homes.

Trends in Amhara are as troubling as those in Oromia.

Trends in Amhara are as troubling as those in Oromia. The state is the country’s second largest, with a population of around 29 million, and was another locus of mass unrest in the years leading up to Abiy’s rise to power. Some leaders within the Amhara Democratic Party (ADP) – at the time, the Amhara National Democratic Movement – backed the protests, like their Oromo counterparts, seeing them as an opportunity to loosen the TPLF’s grip. Indeed, Abiy owes his premiership in part to a tactical alliance between Oromo and Amhara leaders, who took advantage of the growing realisation within the coalition that only genuine change could placate protesters, outmanoeuvred the TPLF and appointed Abiy as EPRDF leader at the coalition’s March 2018 Council meeting.

As in Oromia, protests in Amhara whipped up ethno-nationalist sentiment, now entrenched in the region’s political discourse. The result is an increasingly salient narrative that presents ethnic federalism as a TPLF-dominated project aimed at subjugating the region. True, many ethnic federalism critics – including a large number of Amhara but also many others – promote a pan-Ethiopian vision and portray ethnic federalism as eroding national unity. They argue that it renders as second-class citizens minorities in states delineated for dominant ethno-linguistic groups, not least because they face barriers in pursuing government services and public office. They contend that, by placing ethnicity at the heart of politics, the system feeds ethnic conflict and may even sow the seeds of the state’s collapse. But much Amhara opposition to the system also has an ethno-nationalist and anti-TPLF flavour. The transition has spawned a new party focused on asserting Amhara rights, the National Movement of Amhara (NaMA), which presents itself as a defender of Amhara, including those living outside the Amhara region.

Pressure from that movement partly explains the ADP’s ill-fated November 2018 appointment of Asaminew Tsige as regional security chief. Asaminew, a strong opponent of the TPLF, was jailed in 2009 for his role in a coup attempt and then pardoned by the federal government in February 2018 as part of an amnesty by then-Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn. By appointing him, the ADP hoped to boost its popularity to the detriment of its ascendant ethno-nationalist Amhara opposition. The move proved disastrous. On 22 June, Asaminew reportedly directed the assassinations of Amhara leaders in the regional capital Bahir Dar and Ethiopia’s military chief of staff, the Tigrayan General Seare Mekonnen, in Addis Ababa, before himself being killed by security forces.

The recent bloodletting in Oromia, and Amhara-Oromo fighting at several universities, have sharpened tensions.

During his short tenure, Asaminew stoked Amhara nationalism. He worsened the bad blood between Amhara and Oromo by warning of impending Oromo domination. Already, the Amhara-Oromo alliance that brought Abiy to power was strained, with Amhara and others angered by an ODP statement that the federal capital should be under Oromia’s control. They perceive the destruction in early 2019 by Oromia’s government of allegedly illegal settlements, including many non-Oromo homes, on the capital’s outskirts as an assertion of Oromo power. In July, the tens of thousands attending Asaminew’s funeral showed the continued draw of Amhara nationalism, and thus the Amhara leadership’s narrow space for compromise. The recent bloodletting in Oromia, and Amhara-Oromo fighting at several universities, have sharpened tensions. Attacks on Orthodox churches heighten concerns, flagged especially by the National Movement for Amhara, about the safety of Amhara living in Oromia. Mounting religious tensions risk edging a political dispute over Amhara-Oromo federal power sharing into a sectarian contest.

Tigray is another hotspot. The region’s ruling party, the TPLF, controls a northern region representing only around 6 per cent of the country’s population but that for years dominated the EPRDF and federal security apparatus and still enjoys outsized influence in the armed forces. On arriving in office, Abiy replaced many TPLF ministers and security heads, partly in response to widespread sentiment that the TPLF was to blame for years of repression and graft. The attorney general, a senior member of Abiy’s party, issued an arrest warrant against former national intelligence chief Getachew Assefa, a TPLF politburo member, who is now in hiding. Articulating a widely held view, a senior federal official says the government has found evidence of the TPLF fuelling conflict across Ethiopia over the last eighteen months in order to destabilise the state.

TPLF officials reject this allegation and resent what they sense is an attempt to sideline the Tigray. They say Abiy’s government applies selective justice, most prominently by failing to prosecute the many high-ranking non-Tigray officials who served in past administrations and also stand accused of abuses. In their minds, figures like Asaminew who had been released as part of a wide-ranging amnesty were far more deserving of prosecution than TPLF leaders. TPLF leaders are also angry at the displacement of around 100,000 Tigrayans, mostly from Amhara and Oromia regions, during and after the 2015-2018 anti-government protests.

The TPLF’s waning fortunes have not only fuelled Tigray anger at Abiy’s government but also energised long-held Amhara claims over two territories, Welkait and Raya, in Tigray region. Amhara leaders believe that the TPLF annexed those territories in the early 1990s and then encouraged Tigrayans to move in, altering their demographic makeup. Tigrayans argue that the two territories’ administration status should be decided on the basis of self-determination but that only current residents – not those who have left over the past nearly three decades – should have a say. The TPLF rejects the mandate of the federal Administrative Boundaries and Identity Issues Commission, which Abiy set up in December 2018 to look into the Amhara claims and other territorial disputes. Tigray leaders argue that the body is unconstitutional, as its mandate overlaps with that of parliament’s upper chamber, though probably their fear is primarily that it will rule in Amhara’s favour.

The Amhara-Tigray tensions could be the country’s most dangerous.

The Amhara-Tigray tensions could be the country’s most dangerous, as they have the potential to draw two powerful regions into a conflict that could carry risks of fracturing the military. Warning signs continued to flash between Amhara and Tigray in October and November 2019. Another fatal attack on Tigrayan militia by rebels from Amhara reportedly took place at the regional border in the disputed area of Welkait. Renewed violence between Amhara security forces and militia comprising Qemant people left tens dead; the Qemant are a minority in Amhara pursuing greater autonomy but their Amhara opponents say they are TPLF-backed, a claim a military officer involved in pacifying the area said there was no evidence to support. For their part, some TPLF officials claim that they have organised a standing Tigray militia, to defend a “security fortress” in the northern province.

Alongside the worrying signs, there is one positive development. Amhara and Tigray’s leaders, encouraged by Abiy, have recently been in contact. Senior Tigray officials express a desire to ratchet down tensions: “We have to have a fraternal discussion”, one told Crisis Group. Those talks could set out a path toward resolving the territorial dispute.

A last hotspot lies at the country’s opposite end, in the diverse Southern Nations region, hitherto ruled by the fourth EPRDF party, the fragmenting Southern Ethiopian People’s Democratic Movement (SEPDM). There, ethnic groups have seized on the political opening to call for enhanced autonomy. The largest, the Sidama, pressed their constitutional right to hold a referendum on establishing their own regional state. In July, as authorities missed the deadline for the vote, Sidama protesters clashed with police and later attacked minorities. The government deployed troops to contain the fighting, partly by using lethal force. When voting took place on 20 November, it passed off peacefully and resoundingly favoured statehood. But if authorities fail to manage high Sidama expectations about the pace of creating the new region and bring economic benefits, there could be more unrest. The government also faces an uphill battle to dissuade other Southern Nations groups from pressing statehood claims. Should the regional state architecture fracture, they could struggle violently for power and resources.

IV. Abiy’s Merger Plan and Ethnic Federalism

Prime Minister Abiy’s moves to expand and unify the ruling EPRDF coalition, motivated partly by his desire to bolster national unity, instead risk fuelling the centrifugal forces pulling at the country’s ethnic fabric. On 16 November and 21 November, the coalition’s Executive Committee and then its Council approved merging the four ruling coalition parties, plus the five parties that control the Afar, Benishangul-Gumuz, Gambella, Harari and Somali regions and that are allied to, but are not part of, that coalition, into a single unified party, the Prosperity Party. The reforms, which several parties’ general assemblies also endorsed, aim to overhaul a system that Abiy and many other Ethiopians see as the root of many of the country’s challenges.

The new Prosperity Party would centralise decision-making, rebalancing authority between its executive organs and its regional branches.

The new Prosperity Party would centralise decision-making, rebalancing authority between its executive organs and its regional branches. The upshot would be that organs at the central level would exercise greater power than is currently the case within the EPRDF, in which regional parties until now have been powerful independent entities. According to the party’s draft bylaws, a key change would be that a National Congress would directly elect representatives to the new party’s Central Committee. Direct election would mark a departure from the EPRDF system in which its 180-member Council – its key decision-making body – comprises 45 delegates from each of the regional party’s central committees. Moreover, the party’s national leadership would nominate the heads of its regional branches.

The merger also arguably represents a step away from formal ethnic power sharing. Under the current system, the mostly mono-ethnic parties at the EPRDF alliance’s core run regional states in which those ethnicities predominate. The principal ethno-linguistic groups in each region thus enjoy substantial autonomy over local decision-making, including choosing the administration’s working language and security management. The proposed reforms open the new party’s regional branches to individuals from all ethnicities and mean that its central committee will not be formally composed of ethno-regional blocs.

Opponents perceive this change as inching away from ethnic federalism.

Opponents perceive this change as inching away from ethnic federalism toward a system based on territory but not identity. The new party’s draft bylaws suggest that representation in its National Congress will be based on the population size and number of party members in each region, indicating a move to majoritarian politics, an inevitable consequence of which would be to favour the Amhara and Oromo. Critics also claim that after the election, Abiy wants to amend the constitution to become a directly elected president. A senior federal official, however, said the parliamentary system is likely to remain, even if there is a constitutional review process – which he does anticipate – after the election.

Much of the EPRDF leadership formally supports the merger.

Much of the EPRDF leadership formally supports the merger. Amhara Democratic Party leaders welcome it. They believe that Abiy’s new party marks a step away from ethnic federalism and will further strip the TPLF of influence in federal institutions. For now, the ADP’s ethno-nationalist rivals in Amhara also favour moving away from ethnic federalism, which they also perceive as a system designed to impose Tigrayan dominance at their expense. ODP leaders formally support Abiy’s plan, though there are signs of discontent within the party’s ranks. Muferiat Kamil, leader of the Southern Nations ruling party, the SEPDM, who is also minister of peace, backs the plan. Mustafa Omer, acting Somali region president and an Abiy ally, also supports it. In the past, he has spoken of his worries about balkanisation, describing Ethiopia’s decision to grant regional states control of autonomous security forces as a historic mistake.

The merger enjoys additional support from influential figures in society who are weary of the ethnic-based political system. According to Mesenbet Assefa, an assistant professor of law at Addis Ababa University, for example:

The Prosperity Party will help tame the hyper-ethnicised political discourse. It is true that ethnic federalism has allowed a degree of self-governance and use of one’s own language and culture. But it has also fomented hostility that has reached unimaginable proportions in the country. … The new Prosperity Party will help balance pan-Ethiopian and ethnic sentiment. In fact, millions of Ethiopians, especially urbanites who have mixed ethnic heritage and progressive politics, feel that they are not adequately represented in the ethnic federal arrangement.[pullquote][/pullquote]

The plan also generates hostility, however, mostly from those who support ethnic federalism and view the merger as a first step toward dismantling it. TPLF leaders reject it outright, believing that it signals the end of the multinational order. Some argue that ethnic federalism protects Ethiopia from its own history of coercive centralism and cultural homogenisation. Undoing it, they say, would set the stage for a return to rule by an abusive centre or even worse. “The most probable outcome is disintegration. But I am not saying we will let that happen”, said a top TPLF official. TPLF leaders opposed the merger at the Executive Committee 16 November meeting and boycotted the 21 November Council meeting, saying they needed more time to discuss the plans with members and raising procedural objections. The SEPDM upper echelons are reportedly divided on the issue, despite Muferiat’s support. An SEPDM EPRDF Council member told Crisis Group that some approved the merger on the basis of the new party’s commitment to multinational federation, but that they would leave if that was not honoured.

Even within Abiy’s own ODP, many regard the merger warily. They, like Oromo opposition leaders, oppose the outsized influence the TPLF has previously enjoyed but value ethno-regional autonomy, and so are aligned with Tigrayan leaders on federalism. On 29 November, Defence Minister Lemma Megersa broke ranks with Abiy, declaring his opposition to the merger. He contended that the timing was not right for the merger, saying Oromia’s ruling party had not yet delivered on its promises to the Oromo. Lemma’s open dissent is significant, given his prominent role in events leading to Abiy’s assumption of the premiership. As ex-president of Oromia, he was a key figure in a group of EPRDF reformers known as Team Lemma that tacitly threw their weight behind the protest movement, hastening the previous administration’s exit. Lemma was a leading candidate for the premiership until February 2018, when Abiy replaced him as Oromo party leader as Lemma did not hold a federal parliamentary seat, a prerequisite to become prime minister. Oromo activists also dislike the plan. According to Jawar:

[pullquote]Sooner or later the merger will start to erode the federal system. The groups won’t be able to collectively bargain. It’s too early to dismantle ethnic-based national organisations.[/pullquote]

That said, for now Abiy’s dissenting colleagues and Oromo rivals appear set on waiting to see what emerges from the Prosperity Party. They will take on the new party at the ballot box if they believe that it will erode Oromia’s autonomy or otherwise thwart Oromo interests. Jawar himself pledges to run for either the Oromo or the national legislature, though he would have to relinquish his U.S. citizenship to do so. Indeed, forthcoming elections could pit supporters of ethnic federalism, including Abiy’s Oromo rivals and the TPLF, against its opponents, led by Abiy’s new party.

So far, Abiy’s efforts to win over the Prosperity Party’s detractors have largely fallen flat.

So far, Abiy’s efforts to win over the Prosperity Party’s detractors have largely fallen flat. The prime minister has asserted that the merger will not affect ethnic federalism and his supporters deny that it aims to whittle down regions’ influence. But to many opponents, the plan to strengthen the central party at the expense of its regional blocs suggests the opposite. Because the EPRDF and the federal structure came into being together in the early 1990s, the two are intertwined and widely associated with one another. Moreover, Abiy’s advisers and appointees include critics of ethnic federalism. Opponents also perceive Abiy’s doctrine of medemer, or synergy, about which he has recently published a book and which will inform the new party’s program, as signalling his intention to undo the system. At its core, medemer stresses national unity, with diverse entities cooperating for the common good. A 22 November statement after the EPRDF Council meeting said the new party would “harmonise group and individual rights, ethnic identity and Ethiopian unity”.

V. Calming the Tensions

The intra-Oromo tensions, plus those between the Oromo and Amhara, the Amhara and Tigray and the TPLF and Abiy’s government, threaten to derail Ethiopia’s transition. Direct armed confrontation sucking in regional elites and federal politicians and potentially splitting the military high command appears unlikely, at least for now. Indeed, the army is performing a crucial role managing flashpoints, and it has remained a beacon of multi-ethnic cohesion despite the 22 June assassination of its chief of staff. But the consequences of such confrontation, were it to happen, would be catastrophic, raising the spectre of all-out civil war and the fracturing of eastern Africa’s pivotal state.

Abiy’s overarching problem in calming those tensions is that acceding to one group’s demands risks eliciting violent reactions from another.

Abiy’s overarching problem in calming those tensions is that acceding to one group’s demands risks eliciting violent reactions from another. Many Ethiopians demand action against Jawar for his role in the late October bloodshed. But moves by the authorities against him are likely to stir up more turbulence in Oromia and further weaken Abiy’s base. If the government meets Oromo demands – awarding them greater administrative power over Addis Ababa, for example – it would trigger resistance from other groups, especially Amhara. Any federal attempt to assuage the TPLF’s concerns at its marginalisation could provoke opposition from the many Ethiopians who blame it for an authoritarian system’s past excesses. Backing Amhara’s territorial claims could lead to confrontation with Tigray’s well-drilled security forces.

The dilemma for the prime minister related to ethnic federalism is equally pronounced. Until now, he has largely trodden a middle path between proponents and detractors. But his ruling party reform moves him more concretely into the latter camp, raising the prospect of fiercer resistance by those who see preserving the system as in their interests. At the same time, mollifying that group risks leaving behind a pan-Ethiopian constituency that is influential in urban areas yet holds little formal power, and which would like to turn the page on ethnic politics and has largely supported the prime minister until now.

The prime minister and his domestic and international allies can, however, take steps to cool things down.

The prime minister and his domestic and international allies can, however, take steps to cool things down. Abiy’s camp should clearly signal that any possible future formal review of Ethiopia’s constitution would be inclusive of opposition parties and civil society. While some interlocutors describe Abiy as aloof and averse to advice, the premier has started to facilitate cross-party and inter-ethnic crisis discussions. He should continue to foster these. Abiy and his allies should press for intensified negotiations among Oromo factions and between Amhara and Tigray’s leaders. Ahead of the May 2020 elections, Abiy could convene a meeting with all major parties, activists and civil society to help minimise violence and division around what is shaping up to be a high-stakes vote. But if conditions deteriorate further, he could consider a delay to that vote and some form of national dialogue.

As for Ethiopia’s international partners, they should pressure all elites, including opposition figures, to curb incendiary rhetoric. They should also bolster Ethiopia’s economy against shocks that could aggravate political problems and, if Abiy’s government requests it, provide a multi-year financial package to create space for his reforms.

A. Reducing Conflict Risks from the Party Merger Plan

While Prime Minister Abiy is within his rights to spearhead the refashioning of the ruling coalition, he would be better advised to calm fears that the move concentrates power in Addis Ababa and is the beginning of the end of ethnic federalism, an issue that Tigrayan politicians in particular view as almost existential. It will be a hard sell. Signals that Abiy and his allies have sent since coming to power about their intentions to remake Ethiopia’s federation undercut their claims that they do not seek to undo current arrangements. Indeed, for many of Abiy’s supporters, remaking those arrangements is a key political goal and a vocal lobby beyond them supports such reforms. Still, Abiy can reiterate more forcefully that any far-reaching reordering of Ethiopia’s constitutional order under his watch will take place down the line and through a consensual, consultative process, involving not only the ruling party but also other factions and Ethiopian civil society. A process along these lines would also benefit those among Ethiopian society that want to move away from ethnic federalism, by giving them a voice in reforms.

B. Calming Tensions in Oromia

The prime minister should maintain lines of communication with the Oromo opposition and continue to facilitate dialogue between Oromo and Amhara political parties aimed at reducing tensions that occurred after the October violence. Civil society groups such as the Inter-Religious Council and elders from the various ethnic groups should press ahead with their ongoing efforts to stimulate dialogue among both elites and the grassroots. Oromo elders, for example, brokered a January 2019 agreement that helped reduce fighting between federal troops and elements of the Oromo Liberation Front. They have also reportedly played a role in encouraging talks among rival factions in Oromia and should maintain this effort. They should emphasise to rival camps that all parties should channel their competition through the electoral process and discourage violence.

C. Addressing Tigray Alienation

The government ought to start reversing Tigray’s dangerous alienation. While its politicians will inevitably lose from more representative politics, there are ways to mend bridges. The Tigray elite have already displayed a capacity to act in the national interest over the past two years. Although often portrayed as having retreated to their Tigray fortress in anger after losing their dominant position in Addis Ababa, parts of the Tigrayan leadership in fact displayed considerable restraint by relinquishing their grip on power. In early 2018, many feared Ethiopia was careening toward civil war amid the three-year grinding confrontation between protesters and the security state. By ceding control, TPLF heavyweights took a difficult but inarguably wise decision. Prime Minister Abiy and his allies can now take steps to persuade them to more substantively rejoin the conversation at the centre of Ethiopia’s future.

A first step would be to ease Tigray-Amhara tensions and Tigray disquiet over Amhara’s territorial claims.

A first step would be to ease Tigray-Amhara tensions and Tigray disquiet over Amhara’s territorial claims. Abiy’s government could continue to encourage Amhara and Tigray leaders to intensify and broaden promising initial discussions aimed at easing their mutually hostile relations, while pressuring hardliners to allow such conciliatory steps to occur. The Administrative Boundaries and Identity Issues Commission could assert that it aims to resolve the status of the disputed territories on the basis of self-determination, even if leaving open questions of who has a say in their future. In turn, Tigray leaders might reconsider their rejection of the commission’s role.

Abiy and his allies could also reconsider what the TPLF perceives as a one-sided campaign of prosecutions of leading Tigrayans. Though Tigrayans were prominent in the previous administrations, leaders of other major ethnicities were also present in federal security organs. Besides, to portray the former regime’s legacy in a purely negative light would be misleading: it built vital infrastructure, revived an economy battered by years of civil war, and oversaw major advances in basic health care and education for the large impoverished rural population. Transitional justice might be better implemented after ongoing reforms to judicial and investigative organs are complete.

For its part, the TPLF could show greater pragmatism. Rather than adopting a siege mentality and drawing red lines on issues like the ruling coalition merger, its leaders could seek compromises with Abiy’s government in the same spirit that some of them show toward nascent discussions with their Amhara counterparts. Further, if a national dialogue takes place, Tigrayan elites might want to own up to some of the abuses that took place in the three decades in which they controlled key state organs. Such a good-will gesture would hasten national reconciliation and might reduce opposition to steps to end prosecutions.

D. Reducing Election Risks and Setting up a National Dialogue

The prime minister’s office has reaffirmed that the government intends to hold the vote on schedule – understandably so, given his desire to achieve a popular mandate to push forward with his reforms. Moreover, the legal procedure for deferring the vote past May’s constitutional deadline is unclear and a postponement could expose the premier to questions about his legitimacy.

If the vote proceeds, dialling down tensions beforehand will be critical. Abiy and his allies could convene a national conversation with opposition parties and civil society to discuss campaigning and election procedures, including the security management of contested cities that are electoral hotspots and how to ensure that state institutions and public officials do not support the ruling party, as occurred extensively during past elections.

This forum could help on a number of fronts. It would offer a chance to limit expectations: even with the best of intentions, polls will be marked by challenges, given that the new electoral board is still finding its feet and opposition parties, media and civil society monitors remain weak. It could allow Abiy and the authorities to build good-will and encourage parties to pledge not to campaign divisively or view the vote as an existential, winner-take-all affair. Abiy himself might promise to form, if he triumphs at the ballot box, an inclusive government, for example by bringing in regional leaders in the cabinet even if they opt not to join his new party. Initial discussions are also necessary on how to improve inter-governmental coordination in a federation facing a post-EPRDF future, where opposing parties may control the central and regional governments.

If the political temperature rises further, Abiy may have to seek an election delay.

If, however, the political temperature rises further, Abiy may have to seek an election delay. A divisive and bloody campaign, with candidates making openly ethnic-based appeals for votes, could tip the country over the edge. Provided that Abiy secures broad support for a delay and uses the time the right way, he should be able to weather criticism. Tigray leaders want the vote on time – in Tigray region, they face little competition or insecurity that could disrupt balloting, and in any case their fears about ethnic federalism mean that they oppose constitutional violations such as election delays – though the steps outlined above aimed at tackling their grievances might help bring them along. Oromo and Amhara opposition actors from Jawar and the OLF to the National Movement of Amhara could back a postponement so long as they were included in any major political discussions.

If polls are delayed, some form of national dialogue, with Abiy presiding, might be an option. Such talks would aim, first, to build consensus on a timeline for transitional milestones, including a long overdue census and new dates for elections, including at village, district and city levels. More importantly, it could set out a process through which Ethiopia’s leaders can try to resolve deep-seated disagreements over past violence, power sharing, regional autonomy, territory and the future of ethnic federalism. According to one top Western diplomat:

[pullquote]The prime minister could say we’re trying to change the country, build on the past, call together a national conversation, trying to build a new national social contract. He could present it as the natural next stage in the nation’s history, orchestrating an extended dialogue that addresses fundamental constitutional issues, such as the degree of federalism.[/pullquote]

VI. International Support

In a country historically suspicious of outside involvement, external actors inevitably are constrained in the roles they can play. But the more open environment under Abiy means that the country’s international partners, including the U.S., Europeans and Abiy’s Gulf allies, can be franker than in the past, even if behind closed doors.

First, outside powers need freshened-up talking points. Ethiopia’s transition still offers great hope and merits all the support it can get. But the continued unmitigated acclaim from abroad appears increasingly out of step with trends on the ground. Now that Abiy has been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, Ethiopia’s international partners can offer constructive criticism as well as plaudits. The prime minister foreign allies should nudge his government toward a more cautious and consultative approach. They should pressure Oromo, Amhara and Tigray elites, including Jawar and other opposition figures, with whom many international actors have contacts, to avoid inflammatory rhetoric. They should encourage all Ethiopian leaders to defer contentious demands over federal power sharing, regional autonomy and territory until after the May elections or, if they are delayed, until some form of national dialogue or other consultative process is in place. They should back an election delay if one becomes necessary.

International partners should use financial aid and technical support to protect Ethiopia from economic shocks.

Secondly, international partners should use financial aid and technical support to protect Ethiopia from economic shocks, such as from a reduction in construction jobs due to diminished infrastructure investment, large-scale layoffs of civil servants, increased external debt-servicing costs due to devaluation of the national currency, the birr, or basic commodities prices hikes. In today’s fraught environment, economic discontent could easily incite protests, dangerously compounding communal divisions. International partners should also be ready to discuss a comprehensive package of support for institutional and economic reform during a multi-year transition, if the government requests it. Western governments could consider following China’s lead and offering Abiy’s government debt relief, which could reopen some fiscal space to maintain public investment in vital infrastructure projects that create jobs for a youthful population.

VII. Conclusion

Since taking office, Prime Minister Abiy has tried to drive Ethiopia’s transition from the centre, straddling a line between ethno-nationalists and opponents of ethnic federalism. But his plan to transform the ruling coalition has widened a fault line that has bedevilled the Ethiopian state for decades, between those who see ethnic federalism as a bulwark against the coercive centralism of the past and those who view it as a source of division and violence. Moreover, even as Abiy and his allies attempt to push forward reforms, they have to grapple with other challenges, perhaps most urgently ethnic strife that could tip the country into wider conflict and an under-employed young cohort demanding greater economic opportunities.

Ethiopia has long been an anchor state in the restive Horn of Africa. Its three-year uprising arguably served as a model for later protests in the neighbourhood. Many are watching its delicate transition to a potentially more open era with considerable expectation. Ethiopian leaders and their foreign allies should redouble efforts to prevent a breakdown and to shepherd the country to a better future.