The ICJ hearing comes with high risks for both sides. Its postponement offers the interdependent neighbours another chance to talk.

If and when Kenya and Somalia’s maritime dispute is heard by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) next year, one aspect of the two neighbours’ long-running quarrel will finally conclude. It will be decided once and for all which country rightfully controls the small but resource-rich section of the sea being contested.

However, even if we reach a ruling, it will not mark the end of the story. And, instead of settling the issue, the verdict could lead to a further deterioration in relations. Rather than there being a winner and a loser from the process, both Kenya and Somalia could end up as losers.

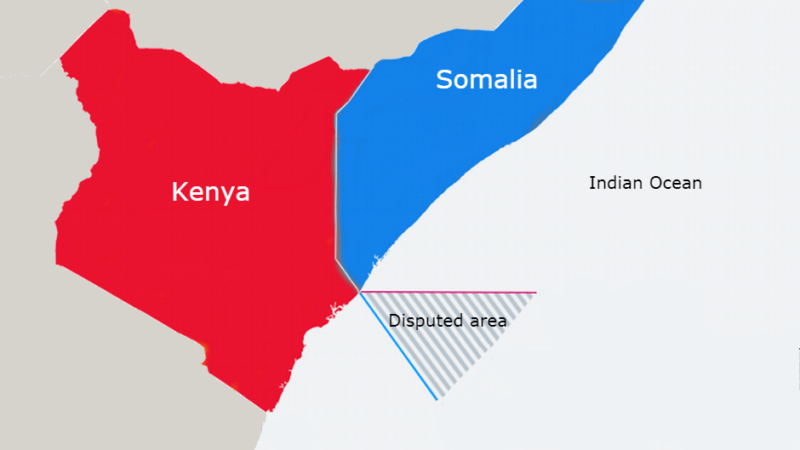

The area under dispute is approximately 100,000 square kilometres and is thought to contain large deposits of oil and gas. Both countries claim the area as theirs, Kenya arguing the sea border should be drawn parallel to the line of latitude, Somalia saying it should extend in the same direction as its land border.

This fundamental disagreement led Somalia, in 2014, to call on the ICJ in The Hague to resolve the dispute. The hearing has now been set for June 2020.

Kenya has tried to convince Somalia to drop the case and settle the matter outside of court. It sees the dispute as an existential threat that is about more than potential oil and gas deposits but its access to the Indian Ocean.

Somalia has resisted this pressure. As the weaker party and with fewer regional backers, it believes its best interests lie in the international legal system. Encouraged by nationalist sentiment in the country and the diaspora, it has stuck to this strategy.

This disagreement has led to growing tensions. Many are concerned about what might happen following the ICJ ruling. While the court’s decision is final and binding under international law, it cannot enforce it. ICJ rulings have been ignored in the past and there is no guarantee both parties will accept it.

After all, the issue has already become hugely politically charged and treated as a matter of national integrity. This August, Kenyan parliamentarians called on President Uhuru Kenyatta to consider sending troops to the maritime border to protect the “sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Republic”. Somali lawmakers suggested they would be prepared to respond in kind.

Risks on both sides

In recent months, the two neighbours have come to see each other as adversaries, but this should not be the case. Kenya and Somalia have far more to cooperate on than feud over. They are deeply intertwined and interdependent. For instance, Kenya is a major troop contributor to the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) which has been crucial in containing al-Shabaab, a threat that affects both countries. Moreover, Kenya has a hugely significant Somali population and, since the Somali state collapsed in 1991, has hosted hundreds of thousands of its neighbours.

In the long-term, Kenya and Somalia both need each other much more than they need the contested triangle of maritime territory. Furthermore, whichever way the ICJ rules, the two parties would need to sit down and talk. The ruling will not end the dispute, but simply mark the start of its next chapter.

Negotiating is not only necessary but would be in both countries’ interests. In fact, the main party that would gain from the lack of talks and a deterioration in relations would be the Islamist militant group al-Shabaab. If Kenya were to pull back its 4,000 troops from Somalia, AMISOM’s capabilities would be severely weakened. Meanwhile, al-Shabaab has already been using the dispute with Kenya as a recruitment tool. In September, its leader Ahmed Diriye issued an audio message condemning Kenya’s maritime claims and other forms of foreign “invasion”.

Since Somalia took the case to the ICJ in 2014, the two parties have failed to settle their maritime dispute through bilateral talks. The recent delay in the hearing from its scheduled date in November to June next year offers another window of opportunity for both sides to engage in good faith talks rather than resorting to diplomatic pressure and heightening tensions.

In the absence of this, an eventual international ruling would break the impasse, but with high risks for both sides. A verdict in favour of Somalia could, among other things, push Kenya to contest its southern sea border with Tanzania, leading to a destabilising domino effect of disputes down to Mozambique, Madagascar and South Africa. A verdict in favour of Kenya could damage a fragile Somali state and embolden al-Shabaab which has already said it “will never accept, and are against any decision made by the so-called International Criminal Court”.

Worse still, both possible win-or-lose verdicts risk exacerbating tensions between Somalia and Kenya, which would be bad for both sides. If this happens, one party may win, but both will lose.