Fair Fishing is a nonprofit that seeks to drive economic growth and improve nutrition and food security in Somaliland, hoping it’s a model for the region.

Mustafa Abdullahi grew up in Somaliland, the peaceful, democratic, autonomous republic that broke away from neighboring Somalia in 1991.

After selling his successful taxi business in Bristol, England, last year, Abdullahi could have taken a break from work. Instead, the 39-year-old and his business partner returned to Somaliland to start a fish distribution and retail business, called Horn Foods. It’s a cornerstone of the country’s developing fishing industry, nicknamed the Blue Economy.

“I am always looking for the next challenge—that’s why I wanted to return,” Abdullahi says.

He came to the right place. The tiny coastal village of Buluhaar sits at the edge of the Indian Ocean, with bountiful stocks of tuna, kingfish, and other types of fish. Yet not a single villager even knew how to fish until last year.

“The biggest fish stocks are there, but the culture has nothing to do with the sea,” Abdullahi explains. “It’s a nomadic culture; it’s all about the camels. This is hard work, but I think it will pay off.”Somaliland’s small but thriving fish sector is a tale of unintended consequences and serendipity.

In 2008, Danish ship owner Per Gullestrup’s crew was hijacked by Somali pirates and later released. Three years later, Gullestrup came up with an idea to help develop alternative livelihoods in the region. He launched Fair Fishing, a nonprofit organization, with the aim of creating jobs, driving economic growth, and improving nutrition and food security. It began in Somaliland as a model, with the support of a stable government.

Unlike Somalia, Somaliland has little history of fishing outside the small coastal city of Berbera. The bigger problem was shifting the mindset of a meat-eating society to fish. A campaign providing nutritional education, raising awareness, and changing perceptions were the first steps. Traditionally, fish was seen as an option only for those who couldn’t afford meat.

Alongside its efforts to promote the nutritional benefits of seafood, Fair Fishing also launched training programs providing technical skills (including swimming) and teaching people how to fish, repair nets and boats, clean and fillet, store and sell, and prepare and cook fish. Fishing supplies are sold at cost, and a handful of boats have been donated.

As the campaign began to gain traction, the impacts of climate change made fishing a necessity. Livestock contributes more than 30% to the national GDP. But more frequent droughts, including one in 2017 that killed more than half of the country’s goats, sheep, and camels, devastated the economy and have threatened the survival of large families of pastoral nomads.

Somaliland’s government began prioritizing the development of its fish industry as a sustainable food supply with commercial export potential.

EXPLOITING THE “BLUE ECONOMY”

Vice President Abdirahman Ismail has big hopes for the state’s 500 miles of coastline.

“We have to shift our dependence from land to sea. The exploitation of the blue economy is under-developed. We’re only catching less than 10% of what is available in our fish stocks. Fishing has the power to transform this country’s economy and could contribute up to 6% of our GDP.”

Since it began eight years ago, Fair Fishing has created 3,000 jobs in Somaliland. An independent impact report produced this year found the income for those in the fishing industry grew more than 300% from 2013 to 2018. The average monthly income for a fishing crew rose from $150 in 2012 to $470 in 2018.

Government officials want to develop coastal communities in order to resettle displaced nomads and give them the training and resources to participate in the blue economy.

The impacts of Somaliland’s growing fishing industry are already being felt inland, in cities such as Burao and the capital, Hargeisa, where fish restaurants and shops have multiplied in the last few years, many of them owned by women. Some have saved enough to buy their own boats and now employ men to fish.

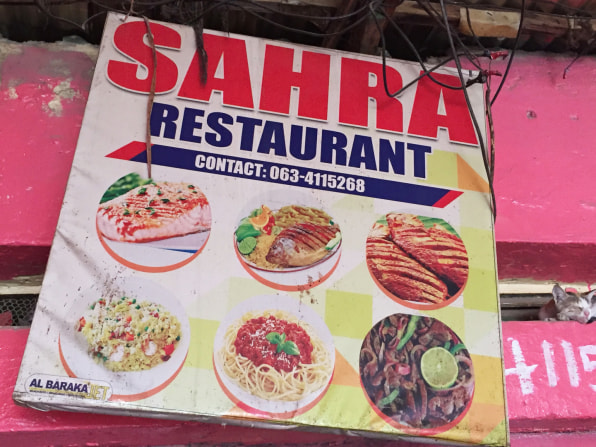

Sahra Muhammed, who owns one of the 100 fish restaurants in Hargeisa, has seen her business grow from a street food stall selling fried fish into a sit-down restaurant with 36 covers.Muhammed has tripled her income and now employs six men and women. Nearly all were affected by the drought and support their families through their work at the restaurant.

Abdi Hashi cooks and waits tables. He came to Hargeisa after his family’s animals were wiped out in the 2017 drought.“I will never go back to the nomadic life,” Hashi says. “Everywhere you go, you will find nomadic people who have come to work in the fish industry because it’s bringing jobs and opportunities.”

Hashi and others are fish converts not only because of the financial opportunities and sustainability, but also because Somalilanders have become more aware of the nutritional benefits.

“My kids never used to eat fish. Now, they’re used to it, and they love it. It pleases me because it’s good for their nutrition, their health, their physical and mental development. We eat it for lunch and dinner.”

Demand increased so much that Fair Fishing donated solar-panel-powered freezers and an ice machine to the village of Buluhaar, where Muhammed Abdullahi sources fish for his business. The freezers serve a dual purpose. Individual fishermen store their inventory until they sell it, paying a small fee to the community for ice and storage. Mayor Ismail Mohamed says the income has helped pay for vital services, such as a new school.

“There was nothing here. People didn’t have any work. There was no school, no medical access. Now, fishermen are making about $250 per month. That’s a good living in Somaliland.”Abdullahi has set up a training program in Buluhaar to feed his supply chain. He teaches technical skills (including safety at sea) to cultivate his own workforce of fishermen and those skilled in logistics and processing to pack climate-controlled trucks for the three-hour journey to Hargeisa. In just six months, Abdullahi and his partner have grown Horn Foods to 11 shops, with a wholesale business supplying hotels. Eventually, they’d like to develop an export market in neighboring, landlocked Ethiopia. For now, Abdullahi is pleased with the rapidly expanding market at home.

“First, people began eating fish once a week. Now, we’re eating fish four times a week. Slowly, we’re changing from a red-meat culture to a fish culture. We are transforming the economy.”

BY AMY GUTTMAN

Amy Guttman is a London-based journalist working in TV, radio and digital/print. She covers current affairs, entrepreneurs, and ecosystems around the world.