The annual U.N. General Assembly is an orgy of symbolism. Who meets whom on the sidelines? Who tried but failed to secure a meeting with the U.S. president? Who walks out of whose speech? Whom do security officers intercept when they try to exceed the permissions of their visa?

But there’s a second chapter to the diplomatic saga: Who continues on to Washington? What they do there matters. Some go to the White House, others to Congress, and still others hold meetings with their respective diasporas.

President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, or Farmajo as he is known to his Somalia constituents, visited Washington, D.C., to formally open the Somali embassy. Farmajo was once the State Department’s great hope for Somalia. Long a refugee in the United States, he acquired American citizenship and even worked in various local government posts in Buffalo, New York, before returning to Somalia to become president.

The State Department sent Donald Yamamoto, one of its highest ranking Africanists, to head the U.S. mission in Mogadishu. Yamamoto, in turn, promised Somalia almost a billion dollars in aid, although that number has shrunk considerably because of Farmajo’s ineffectiveness against (if not participation in) endemic corruption and a host of unanswered questions about his governance and priorities.

U.S. priorities in the Horn of Africa are promoting peace and stability, countering terrorism, and preventing Chinese inroads. On the latter two counts, Farmajo has already become a liability. He has sold Somali waters to Chinese interests, for example, undercutting Somali fishing and aiding a revival of piracy. In recent months, he has appeared to endorse terrorism as a policy tool against neighboring states.

His visit to Washington should now end any question about whether the Farmajo regime deserves U.S. support.

Less than six months ago, the revelation that an Uber and Lyft driver in the Washington, D.C., area was a confirmed war criminal made international headlines. At the time, numerous Somalis testified that the driver, Yusuf Abdi Ali (better known as Colonel Tukeh), had directed torture and gruesome executions of prisoners during the 1980s.

In one case, he had tied prisoners to a tree, doused them with oil, and lit them on fire. In another case, he tied a prisoner to a military vehicle and dragged him to his death. The cases were well documented, and so when Abdi Ali was found living in Canada, the Canadian government deported him. He later entered the U.S. and found work as an airport screener until he was recognized. Ultimately, after a long legal battle, the Federal Court in Alexandria, Virginia, found Abdi Ali guilty and fined him $500,000 in the case of Farhan Tani Warfaa, a Somali whom Abdi Ali had tortured and shot five times while Warfaa was a teenager.

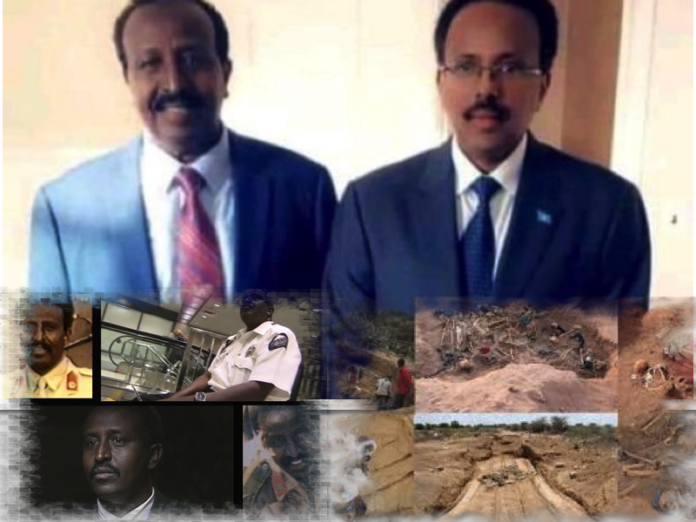

Human rights activists and Somalia watchers were shocked, therefore, not only to see Abdi Ali attending the opening of the new Somali embassy in Washington, but also to pose for pictures with Farmajo. Politicians might get a pass when asked to pose by well-wishers whom they do not know. But in this case, Abdi Ali appeared to be working for Farmajo, setting the security perimeter.

No diplomatic smoke and mirrors can obfuscate Farmajo’s behavior. He is seeking to appeal to the worst elements of his clan rather than promoting reconciliation. In Somaliland especially, where the bulk of former dictator Siad Barre’s genocide against the Isaaq clan occurred, the wounds are still fresh and mass graves still uncovered.

Yamamoto’s strategy has effectively been one of bribery: Flood Mogadishu with aid and allow Farmajo to use it to grease patronage to unite Somalia. The strategy has not worked, however, and instead has worsened corruption, undercut development by distorting salaries, and undermines stability in Somaliland and the southern Jubbaland state, as well as other portions of Somalia that have also seen modest stabilization and success.

Even before Farmajo’s Washington trip, there were ample grounds for the State Department or Congress to review Somalia policy. For a leader such as Farmajo to pose with a war criminal should be grounds for automatic cessation of support. Somalia cannot recover with Farmajo in power. Both Somalis and American taxpayers deserve better.

By Michael Rubin

Michael Rubin (@Mrubin1971) is a contributor to the Washington Examiner’s Beltway Confidential blog. He is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and a former Pentagon official.