[pullquote][/pullquote]No foreign government recognises Somaliland’s sovereignty, even though it fulfils the requirements for statehood, including the hosting of regular free and fair elections, the capacity to defend itself, and the issuing of its own passports and currency. It faces many economic challenges, but these are slowly being addressed, including expanding its port capacities, building a reliable electricity grid not dependent on diesel, and diversifying the economy.

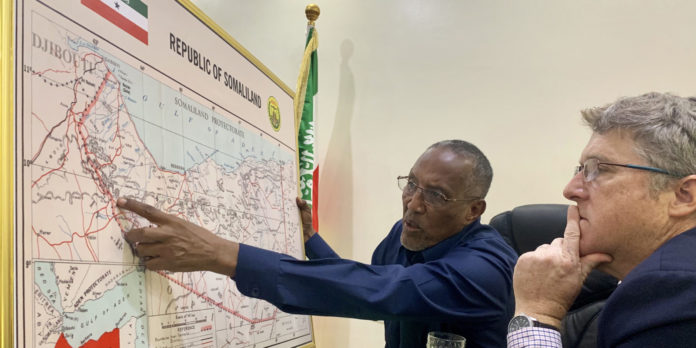

“You see,” says President Muse Bihi Abdi, pointing to an area to the east on the giant map of Somaliland covering the one wall of the presidential briefing room in Hargeisa, “in this area, clan members think ‘I have a gun, I am the government’,” explaining why the area is spotted with Al-Shabaab fighters and his government continues to battle to establish governance.

This has echoes in the observation of the 19th century traveller Richard Burton of the Somali that “every man his own sultan”.

The restive east notwithstanding, a great deal has been achieved by the hitherto unrecognised Republic of Somaliland since its reproclamation of independence in 1991.

Re-proclamation as, three decades before, in June 1960, Somaliland gained its independence from its colonial master, Britain, before making an ill-fated decision to join former Italian Somaliland five days later. This union was then envisaged to incorporate French Somalia (now Djibouti), the Somali-dominated Ogaden region of Ethiopia, and a piece of northern Kenya. That never happened.

Instead, following a bitter civil war that saw the forces of Somali President Mohamed Siad Barre employ Rhodesian mercenaries (among others) to bomb and strip the capital of Hargeisa, the Somali National Movement booted out the occupiers, and set about creating the conditions for stability which have endured since.

A domestic peace process was constructed around five major internal meetings, starting with the Grand Conference of the Northern Peoples in Burao, held over six weeks and concluding with the declaration of Somaliland’s independence from Somalia on 18 May 1991.

Somalilanders concentrated on achieving peace, not on acquiring comforts and financial rents for delegates from the process. This feature has continually blighted Somalia’s overtures to the south, as “conflict entrepreneurs” in Somalia have fed off both the fighting and the talking in a top-down process financed by donors, and which have largely taken place outside the country. The bottom-up process was consolidated through the development of a democracy, again slowly but steadily.

In 2002, Somaliland made the transition from a clan-based system to multi-party democracy after a 2001 referendum, retaining an Upper House of Elders (guurti), which secures the support of traditional clan-based power structures. Regular elections and a regular turnover in power between the main political parties have characterised the local politics.

It’s hyper-competitive too. The 2003 presidential election was won by Dahir Riyale Kahin by just 80 votes out of nearly 500,000 from Ahmed M Mahamoud Silanyo. The tables were turned between the two in 2010. President Bihi was elected in 2017, receiving 55% of the vote. He had served in the Somali Air Force flying Soviet Ilyushin Il-28 twin-engine bombers in the 1977 war that attempted unsuccessfully to wrest the Somali-dominated Ogaden from Ethiopia before changing his allegiance to the rebel Somali National Movement.

As the euphoria of self-government fades, his is an increasingly difficult job. The economy is straining. Infrastructure is poor. The unemployment rate among those under 30, who comprise 70% of the population, is 75%. The chewing of khat (a narcotic plant) is a widespread social blight among more than half the adult population, an effective tax on productivity and foreign exchange, soaking up as much as $700-million in annual imports.

This situation has been worsened by the paucity of skills, as a result of which there is a contrasting dependency on foreign talent. Literacy is under 45%, and just 20% for women. Female genital mutilation, at an estimated 99%, says something else about the state of power relations.

The Somaliland government budget is just $200-million, three-quarters of which is spent on salaries and operational expenses. Annual GDP is estimated at little more than $646 per capita. Electricity is five times more expensive than in neighbouring Ethiopia, at $1 per kw/h, reflecting the dominance of monopolies, which also define the banking and telecoms sectors

Productivity is poor, and growth opportunities few and far between. Outside of remittances, which provide 55% of the GDP of $2-billion, Somaliland depends on its sale of camels and goats, though this has suffered from a Saudi foot-and-mouth disease import ban except during the Hajj, halving the annual exports to 1.2 million. This challenge has been worsened by the related pressure on grazing areas and the current drought, especially in the Haud, a broad strip of rich pastureland that straddles the Ethiopian-Somaliland border.

The government prefers to highlight the absence of international diplomatic recognition as both the principal problem and solution to Somaliland’s challenges.

No foreign government recognises Somaliland’s sovereignty, even though it fulfils the requirements for statehood, including the hosting of regular free and fair elections, the capacity to defend itself, and the issuing of its own passports and currency.

Certainly, the absence of recognition adds a risk premium along with more prosaic management hurdles. Finance sector experts reckon the premium of non-recognition to be “between 7-8%” on the cost of money. The Central Bank of Somaliland has so far been unable to register a SWIFT code, which would enable direct and secure international funds transfers.

Non-recognition also means donor funding for Somaliland’s four million people is around just 15% of the $1-billion received by Somalia. It’s a crazy, cruel and not so beautiful world. The donors have essentially incentivised insecurity, misgovernment and chaos. In Somalia, peace is a multibillion-dollar industry.

Except for the involvement of Dubai Ports World in a $450-million development of the Berbera facility on the Gulf of Aden, supplemented by the Ethiopian government for strategic access reasons, foreign investors are few and far between despite frequent expressions of interest and delegations.

But Mogadishu would have to agree to a divorce. And no government there is likely to do so and survive another 24 hours. It’s about as likely as khat being banned. The hangover would overwhelm any government in Hargeisa, no matter how well-intentioned the measure.

The most immediate challenge Somaliland faces is the transformation of its economy from one based on pastoral livestock herding to one capable of generating employment to deal with the challenge of out-of-work youth, a potential threat to stability.

These reforms will require a sector-by-sector transition from the old way of doing things to a more modern approach, as outlined below.

Livestock: From nomadic pastoralism to modern farming

The Somaliland Chamber of Commerce, Industry and Agriculture estimated that livestock made up 60-65% of the national economy with a population of 10-million goats, five million sheep, five million camels and 2.5-million cattle. These numbers may be out of date, however, and it is difficult to obtain more contemporary figures. The major markets for livestock are Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Yemen and Oman.

The lack of reliable data notwithstanding, all those we interviewed agreed that livestock was the largest economic sector at 29,5% of GDP [1].

Export income from livestock derives almost entirely from the sale of live animals to countries on the Arabian peninsula and Saudi Arabia, in particular during the annual Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca.

The export of live animals for the Hajj involves a network of buying agents in Somaliland, but also in Ethiopia and elsewhere, who procure the animals and transport them to the port of Berbera where between one and two million of the live animals are boarded on vessels and shipped to Saudi Arabia during the 20 days of the Hadj.

This effectively means the biggest slice of Somaliland’s foreign exchange earnings occurs during an annual 20-day window.

At the centre of Somaliland’s economy stands the Blackhead Persian, a breed of sheep that is well adapted to the climate and which is the country’s single largest export.

Although Somaliland struggles to export its livestock because of its unrecognised status, this unique sheep is an exception. During the annual Muslim pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia, more than a million sheep and goats are exported for slaughter in keeping with religious tradition.

But this annual export boon is precarious. The sheep are exported during the Hajj because of sheer necessity. There is simply no other country that can supply millions of sheep for slaughter over 20 days. Somaliland’s sheep are smaller than breeds from other countries and are therefore cheaper. They can also be transported live over a relatively short distance to Saudi Arabia. For the rest of the year, Saudi Arabia does not import Somaliland’s livestock because it says the animals do not conform to its health standards.

The sheep have a South African connection. In the 1940s, South Africa invented a new breed, the Dorper – a cross between the Dorset and the Persian. Its ability to survive in arid conditions and to thrive where other sheep struggle has made it a big part of South African and Australian herds.[2]

There are several unique characteristics of sheep-rearing in Somaliland that should be noted. The sheep are largely raised by pastoral nomads who move the flock from place to place – and from a traditional well to well – in time-honoured fashion. Nomadic herding works if the ratio of animals to pasture allows for the regeneration of grasses, but herds have increased in size, and modern technology – cellphones, for example – cause the movement of herds into areas where it has rained but the grass had not yet revived.

The result has been catastrophic, with some 60% of herds decimated by the recent three-year drought.

This “mobile, opportunistic pastoralism” [3] is not the most efficient or productive way to raise sheep. Disease control and pasture management are much better on fenced lands where grazing can be rotated and the sheep can more easily be dosed and observed.

The containment of flocks to fenced fields would also allow for better management of pasture which improves its carrying capacity, and for selective breeding and the introduction of specialist rams to improve the gene pool.

Access to veterinary services that will reduce losses due to disease and make the sheep more desirable to importers is also improved with proper pasture management and enclosure.

Cattle, camels and goats are also raised and sold at livestock markets in the large cities.

Camel milk is locally consumed, but there is the possibility of an export market for this as it has become popular in Australia, for example, where its health benefits are touted.

There is an opportunity to extend the export market by selling slaughtered animals year-round, but this requires investment and the establishment of cold-chain logistics, allowing slaughtered meat to be chilled from the site of slaughter to the port.

A further diversification option would be the canning of meat, which could create employment and extend the shelf-life of meat products and allow them to be exported more widely.

Agriculture: From rain-fed to irrigated

Agriculture is the second largest productive sector of the economy after livestock rearing. Sorghum has been the traditional cereal crop, but wheat is being investigated as the future mainstay because it requires three months to grow to maturity compared with sorghum’s six months. [4]

The biggest obstacle to cultivation is the shortage of water. Around one-tenth of the land is suitable for cultivation and only half of this is used to grow crops. Government has allocated land for research into dry land crops where 720ha are used to grow sorghum and 76ha to grow wheat, proving that the latter is more suitable.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) has supported projects to build canals for the irrigation of crops.

For irrigation to work, dams need to be built to preserve rainwater run-off. Smaller earth dams require less capital investment and may be constructed by local farmers with the assistance of earth-moving equipment.

The production of cash crops is increasing with the introduction of greenhouses and drip irrigation technology. The agriculture department has begun research into drip irrigation techniques for the growing of tomatoes on a small scale at the department’s headquarters in Hargeisa. This type of cultivation is more suitable for an arid country such as Somaliland.

Cash crops include tomatoes, watermelons, cucumbers, eggplant and onion and there is an export market in Djibouti for some of these crops.

The traditional divide between animal farming and crop farming needs to be altered so that crops are grown as supplementary feed for animals. Farmers with “one hand in livestock and the other hand in cultivation” [5] are needed.

Fisheries: From small boats to commercial vessels

Despite possessing an 850km coastline, reputed to have large stocks of fish that could be sustainably harvested, Somaliland has a small fishing fleet consisting of vessels of between five and 12 metres and this economic activity underperforms when it comes to contribution to GDP.

Fishing output has increased from 10,000 tons in 2014 to 120,000 tons in 2017 [6], but this is reckoned to be below the industry’s potential by some distance.

The reasons for this are many and complex. Somalilanders are traditionally nomadic livestock owners and the possession of animals is associated with status. Fishing obviously does not accomplish this and is looked down on as an activity for the desperate and poor.

The Minister for Finance Development, Su’ad Muse Du’ale, put it this way: “Fishing is looked down on as far as our tradition is concerned – you must have a flock.” [7]

This is, in fact, the case at present. Fishing is conducted on a small scale and the sale of fish is limited to the coastal area due to the lack of a reliable cold-chain for transporting the fish to the interior. It is notable that the capital city of Hargeisa with its large population has no fish market despite its relatively close proximity to the coastline. Fish ought to be a readily available cheaper protein option throughout Somaliland and it ought to have an export market given the short distance to big fish-consuming markets in the Mediterranean which are readily accessible via the Red Sea and the Suez Canal.

In order to increase local consumption and exports, investment is needed in refrigeration facilities at the coast, for transport vehicles and in the cities to extend the shelf-life of the fish.

The development of the transport corridor between Ethiopia and the port of Berbera opens up the possibility of exports to that country, a large market which may be game-changing for the industry

In addition to this, there are high barriers to entry with small locally made boats costing $20,000 each [8]. Less expensive boats might be imported or the price might be brought down by increased competition.

An immediate problem is that the research which suggests fish stocks are vast and untapped is dated and may even be decades old. A fresh survey has been commissioned and ought to give greater insight into the variety of harvestable fish and how they might best be caught.

Oil: From exploration to production

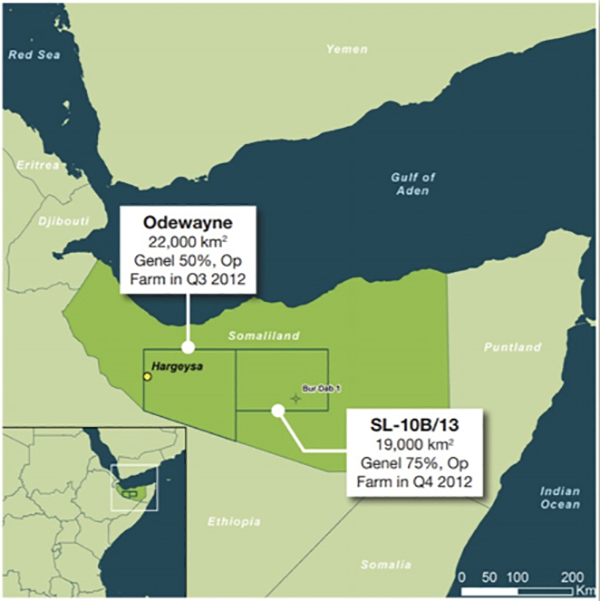

The licence to explore two oil blocks was awarded to Genel Energy in 2012. Exploration in 2015 confirmed there is potential in SL-10B and SL-13 and the Odewayne block with estimated oil reserves of one billion barrels in each.

A further study of seismic data and analysis of the basin has, according to Genel, “led to the maturation of prospects and leads inventory for the SL10B13 block (Genel 75% working interest and operator) which confirms the long-standing view that the block has significant hydrocarbon potential. A number of potentially high-impact exploration targets have been identified within play types directly analogous to the prolific Yemeni rift basins.” [9]

The company says it will initiate farmout – assigning blocks to developers – once these prospects have been quantified in late 2019.

There appears to be a very real prospect that game-changing oil production might get underway in the near future.

In the words of Energy and Minerals Minister Jama Mahmoud Egal, “Most people are looking at our ministry because they see it as the only sector where growth can occur.” [10]

The optimism over the possibility of oil in Somaliland derives from the fact that it shares the same geology as the oilfields on the Arabian peninsula. “The oil is there, it is just a matter of when we get it,” says Egal.

Formal exploration drilling is set for 2020 when the country will finally know if the promising fields can deliver.

To prepare for this eventuality, the ministry has produced several pieces of legislation, including the Petroleum Bill and the Petroleum Revenue Sharing Bill, to create a legal and regulatory environment for the nascent oil industry. But the legislation has been stuck in Somaliland’s slow-moving parliament.

There is the danger that oil will visit the “resource curse” on Somaliland, creating a small extremely wealthy elite with profits moving offshore and creating few jobs for locals who do not possess the skills needed for the industry, which is not, in any event, labour intensive.

To mitigate this, discussions have begun about how to include communities.

The best way to ensure that government’s oil revenues are used to the benefit of all would be to house these in a sovereign wealth fund and use it to address Somaliland’s chronic infrastructure shortages, from the improvement of city roads to the creation of a national electricity grid and a piped water network.

Oil by-products could support other manufacturing industries based on plastics.

Minerals: From small-scale mining to commercial production

Somaliland is believed to have large untapped mineral resources including the largest untapped deposit of gypsum in the world, gemstones, precious metals including gold, and industrial metals including copper and lead.

Mining is, to use the words of Omer Yussuf Omer, the director of minerals, “very primitive” and traditional. [11]

There is some interest from international players with Chinese and Indian firms taking the lead. Chinese firms mine jade while Indian firms are about to begin exploration.

Any mining deeper than 20m requires a mining permit and the state takes a royalty only off exported minerals.

The challenge of scaling up mining is daunting. Any large-scale commercial mining requires an input that is in short supply – water. And Somaliland has no commercial mining tradition, know-how or skills. “We have no mining culture, we are just starting to exploit resources,” says Omer.

Nonetheless, the Somaliland government remains optimistic that it can attract foreign investment and expertise and that minerals could contribute a lot more to growing the economy and employment.

Legislation to regulate mining is also stuck in parliament.

Light manufacturing: From small-scale to processing

Light manufacturing on scale is limited to the bottling of soft drinks and water, with Somaliland – in common with almost every nation on Earth – having a Coca Cola bottling factory.

The plant, some 13km outside of Hargeisa down a winding dirt road through the dust, is evidence that with the right product, access to water via borehole, a local partner and the import of key ingredients, foreign investors can thrive in Somaliland.

Coke made the $17-million investment five years ago with the local Laas Group after a “poignant pitch by our chairman Mr Ahmed Osman Guelleh” in 2009. [12]

Production team leader at the pristine state-of the-art factory, Abdi Fattah Ibrahim started out as a line worker at the plant five years ago. A graduate of Gollis University in Hargeisa, Ibrahim is evidence of the difference that opportunities make.

“I started as an ordinary worker on the machines,” says Ibrahim during a tour of the plant, which also produces bottled water. [13] Down the road, another plant produces fruit juices, using fruit grown in an irrigated orchard – again evidence of what can be achieved with the right investment.

Beyond that, there is the manufacture of materials such as cement bricks for the construction of homes and a small artisanal furniture industry which makes beds, cupboards, tables and chairs.

The manufacture of plastics and foam used in upholstery and for mattresses is also present.

There have been several initiatives to fire up small manufacturing businesses in Somaliland, most notably by the World Bank, which has made funding available for small businesses. Firms cite access to finance (49%) as the single biggest obstacle to growing their businesses, followed by access to land (25%), transportation (8%), tax rates (7%) and electricity (5%). [14]

Access to land in Hargeisa is restricted by high prices, which are driven by the absence of other investment opportunities. There may be somewhat of a property bubble in the capital city. Minister for Finance Development Su’ad Muse Du’ale told us an astonishing fact: “Downtown Hargeisa is as expensive as downtown New York.” [15]

Another reason cited for the lack of growth in manufacturing is that urban Somalilanders are traders – evidenced by the vast number of small traders selling everything from ice cream to mattresses that crowd the side-streets of the city centre.

As a result of the small manufacturing sector, the importing of goods for sale occurs on a large scale relative to the size of the economy, leading to a trade deficit. The latest 2019 statistics suggest there is $202-million worth of exports against $1,205-million in imports. [16]

In addition, the lack of formalisation of businesses leads to weak data and weak revenue for a government which is under-resourced.

The lack of sufficient formal lending facilities and the fact that those who get credit have access to foreign credit markets and loans from families, points to the urgent need for improved financing for small enterprises.

The high cost of electricity and the piecemeal nature of land titling and registration which happens at a local level, are also key constraints.

A new “one-stop-shop” to allow for the quicker registration of new businesses and the formalisation of existing enterprises have been operating for six months, but it appears to have failed to adequately cut red tape and reduce the time it takes to register. [17]

The opportunity exists for Somaliland to leapfrog the traditional economic development step of creating light and heavy industry by growing an innovative ICT sector.

For an industry to thrive, Somaliland’s leaders need the political will to take on vested interests in energy and water supply, which need to be disrupted by cheaper, more efficient suppliers of solar energy and piped water.

There is also the potential for Somaliland to leapfrog the manufacturing phase by focusing on creating opportunities for the youth in the tech space. But efforts to do this are few and far between.

Down an almost unnavigable rocky dirt road in downtown Hargeisa, Bashir Ali Abdi runs Innovation Ventures, which seeks to provide an incubation space for Somaliland tech startups.

The offices provide desk space for young Somalis studying at local schools and universities to develop their ideas for apps and then supports them with marketing these to businesses.

“We need to establish a whole new generation that are tech-based and can contribute to employment,” says Abdi.

The project counts amongst its successes an app that was taken up by World Remit and several others that have been adopted by local businesses.

Abdi puts the youth unemployment figure at 75% and this is borne out by the 1,200 applications he got in 2019 for the 15 places at the institute.

“There’s huge potential in youth. They have the stamina for this kind of business. They want to solve social and economic problems,” says Abdi.

Financial services:

The major financial input into the domestic economy is the inflow of remittances, which accounts for a large portion of GDP and finance spending on household improvements, imports for trade and the growing small construction sector.

Remittances, estimated at $1-billion a year, have been the platform for the launch of three banking groups.

The dominance of the sector by banks with high charges and conservative lending policies has stifled the growth of small businesses and added substantially to the cost of doing business.

The holding up of regulation that would introduce more competition has reinforced the dominance of the three groups.

The absence of international banking groups that have connected global infrastructure has added to the cost of foreign investment and reduced international confidence in Somaliland’s financial management.

The Berbera Corridor:

Captain Hersi is walking down the dock at the port of Berbera. The temperature is a blazing 37ºC – cool for this part of Somaliland, which hits a high of 45ºC in July.

“In 1968, the Russians built this port,” he says as he walks down. A little further on he says: “This part was added by the Americans in 1984.”

Finally, he arrives at the end of the dock where giant yellow construction beams are being welded by young Somalilanders on a training programme. “[The UAE’s] DP World is going to extend the port from here,” he says. [18]

The Russians, who used the Berbera airbase as a forward operating station during the Cold War, the Americans, who tried to establish a foothold, and now the Emirates, bear testimony to the strategic significance of the port on the Gulf of Aden. With the Suez Canal to one side and easy access to the Indian Ocean on the other, the port is positioned to become a key logistics hub.

Should oil be struck in Somaliland, the addition of an oil terminal free of the geopolitical problems which beset the Straits of Hormuz could make Berbera even more significant.

Little wonder that the UAE’s DP World is investing some $442-million in extending the port after a deal that gives it a 30-year concession with the automatic option of extending for a further 10 years. [19] Ethiopia holds a 19% stake in the port development, giving it a vested interest in moving goods via Berbera.

Some 30 ships a month dock at the port, unloading 10,000 containers. But only 20% of the containers go back full, a testament to Somaliland’s poor exports. [20]

Once a year, during the Hadj, the port is transformed as between one and two million sheep and goats are exported for slaughter at the religious event.

The corridor from landlocked Ethiopia to Berbera is the shortest and most convenient route for the passage of goods from the growing Ethiopian export economy.

In addition to this, the UAE is financing the development of the road infrastructure between Berbera and Ethiopia with a view to rerouting some of Ethiopia’s exports, which are entirely dependent on the port at Djibouti, through Somaliland.

The development of the road and the extension of the port by adding 400m of docking is expected to be completed by the fourth quarter of 2020 and the corridor is expected to be fully functional by the first quarter of 2021.

This and the accompanying development of an export processing hub at an SEZ close to the port could ignite the Somaliland economy and provide employment.

The potential to develop manufacturing – the processing, chilling or freezing of meat, fish and fruit, for example, at facilities adjacent to the port – opens up the possibility of increasing exports.

Should the talked-about oil reserves result in production, the addition of an oil terminal at the port could also be extremely valuable to Somaliland. Such a terminal on the Gulf of Aden rather than in the more geopolitically contested Straits of Hormuz could make Somaliland oil a major export to Europe.

Energy: From diesel to solar

A major constraint on the Somaliland economy is expensive energy which is largely produced by diesel generators and then transmitted through an inefficient “micro-grid” system. The plethora of small generators have been consolidated into larger companies such as Sompower, but the grid remains fractured.

The result is that Somaliland has one of the highest – if not the highest – cost of electricity at between $0.70 cents and $1 a kilowatt-hour. By contrast, the cost of electricity in neighbouring Ethiopia is just $0.20 per kw/h. In addition, some 30% of energy is lost during transmission due to the inefficiency of the micro-grids. [21]

The potential for renewable energy is enormous. Somaliland has high solar radiation and an average of 11 hours of daylight throughout the year. [22] In addition, it has an average wind-speed of 12m/second. Although there are several small initiatives – the Ministry of Energy and Minerals building in downtown Hargeisa relies solely on solar energy, for example – only 2% of electricity comes from renewables.

The priorities are two-fold: to reduce the cost of power generation by introducing renewables and other sources – for example, gas, should exploration confirm that this resource is available – and to build an integrated national grid that transmits power much more efficiently.

Conclusion:

The economic challenge – to bring the nomadic livestock-based economy into the 21st century – is enormous. And while the economy stutters along, identity politics increasingly raises an angry head in the east as religious divides between liberals and conservatives harden. It’s not surprising that the government looks for scapegoats and single-bullet solutions.

The solution is more complex, difficult and unfortunately long-term. Recognition is best served, yes, by a process of negotiation, but that will take time and a reasonable facilitator, not one with a regional axe to grind or wider geopolitics to play. For this reason, Turkey, Italy, the UAE, Qatar, and the Saudis are, among others, out.

And the best advocate for recognition is inevitably continued and improving economic success. This will require improving domestic governance, and that will require tax collection, revenue allocation, accountability, transparency and a clear method. As in many African countries, the National Development Process represents a wish list rather than a set of priorities. It will have to address endemically poor productivity, and require action on a range of matters, from ending monopolies and managing vested interests, promoting girls’ education, instigating greater public awareness on the consequences of khat, to taking action on corruption.

Success will require a clear articulation of a national vision, a big idea that citizens can buy into that goes beyond recognition, no matter the extent to which this remains unfinished business for Hargeisa. DM

By Greg Mills, Ray Hartley and Marie-Nouelle Nwokolo are with the Brenthurst Foundation.

References:

[1] Interview Barkhad Ismaciil, Director of Planning in the ministry of trade, industry and tourism, Hargeisa, Somaliland, 27 August 2019. Ismail pointed out that there is little reliable contemporary data on the Somaliland economy and that figures cited were mostly from research conducted by the World Bank for its Doing Business in Somaliland study of 2012.

[2] Information on this breed can be obtained here: http://www.dorpersa.co.za/

[3] Interview with Livestock and Fishery Development, Hassan Mohammed Ali Gaafaadhi, Hargeisa, 28 August 2019

[4] Interview with the Director-General of Agriculture, Dr Ahmed Ali Mah, Hargeisa, 28 August 2019

[5] Interview with the Director-General of Agriculture, Dr Ahmed Ali Mah, Hargeisa, 28 August 2019

[6] Interview wih Barkhad Ismaciil, Director of Planning in the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Tourism, Hargeisa, Somaliland, 27 August 2019

[7] Interview with the Minister for Finance Development, Su’ad Muse Du’ale, Hargeisa, 28 August 2019

[8] Interview with Livestock and Fishery Development, Hassan Mohammed Ali Gaafaadhi, Hargeisa, 28 August 2019

[9] Information published by Genel at https://www.genelenergy.com/operations/exploration-and-appraisal-assets/somaliland/

[10] Interview with Energy and Minerals Minister Jama Mahamoud Egal, Hargesa, 28 August 2019

[11] Interview with Director of Minerals Omer Yussuf Omer, Hargeisa, 28 August 2019

[12]Better brands, better living, Laas Group pamphlet, undated

[13] Interview with Abdi Fattah Ibrahim, SBI plant outside Hargeisa,

[14] Somaliland’s private sector at a crossroads, a World Bank study, 2016, at http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/840741468190160823/pdf/103238-PUB-Box394858B-PUBLIC-DOI-and-ISBN-from-the-doc.pdf

[15] Interview with Minister for Finance Development Su’ad Muse Du’ale, Hargeisa, 28 August 2019

[16] Interview with Barkhad Ismaciil, Director of Planning in the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Tourism, Hargeisa, Somaliland, 27 August 2019

[17] Several officials speaking off the record were sceptical of the impact the one-stop shop had made other than by bringing all the cumbersome registration requirements to one place

[18] Interview with Captain Hersi, Berbera, 31 August 2019

[19] DP World online publication at https://www.dpworld.com/what-we-do/our-locations/Middle-East-Africa/Berbera/somaliland

[20] Interview with Captain Hersi, Berbera, 31 August 2019

[21] Interview with Minister for Finance Development Su’ad Muse Du’ale, Hargeisa, 28 August 2019

[22] This figure was presented by the Ministry of Energy and Minerals