Within the literary sphere, there has oft’ been this argument of what the actual role of the poet ought to be in society. On the one side of this argument are those who believe that the poet does not owe society any allegiance and should be contented with just documenting his thoughts (commitment to art) while on the other side are those who believe that a poet’s loyalty is to his people and the society he belongs. Poets who find themselves in the latter group are of two sub-categories; the first group are those who are content with just pointing out the ills in the society, using their art to incite social revolution, being the voice of the oppressed and downtrodden, and act as the vanguard of society; pointing out the path that society should go even though they do not engage the society physically. However, poets who find themselves in the second subgroup do all that those in the first subgroup do, but they are not content with just documenting the ills in the society alone; they go on to engage the society physically. This second group of poets see themselves as active participants and leaders of change in society; some, like Christopher Okigbo, had dumped the pen to pick the gun, some, like Ngugi wa Thiong’o and Jack Mapanje, had been incarcerated for daring to write against their governments, and others, like Wole Soyinka, have led numerous protests against societal injustice. It begins to appear as if poetry is beyond art, it is also a commitment to one’s society. Today, we shall review a collection of translated poems of a famous and legendary Somali poet; Maxamed Ibraahin Warsame (Hadraawi) and see what the book has to say on the issue of “commitment”.

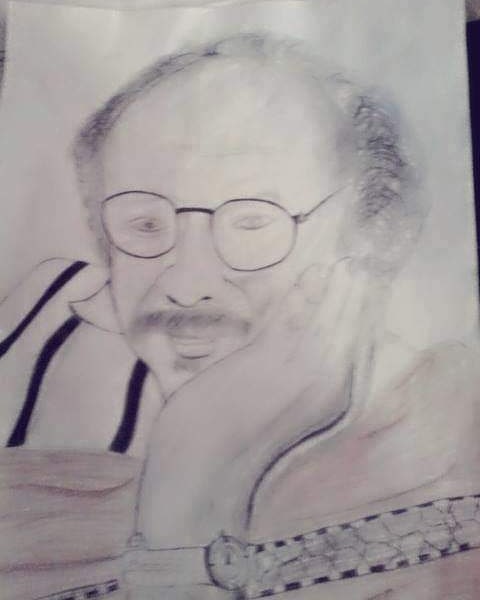

Maxamed Ibraahin Warsame; popularly known as Hadraawi; is perhaps one of the greatest living Somali poet, playwright, and philosopher. His poetry is composed in a sublime form of the Somali language employing vivid images and sound devices (such as alliteration)—indeed, many Somalis can recite his poetry offhand and most of his poems have musical renditions already. His poems bother on issues related to war and peace, love, societal mores and values, maladministration in governance, justice, patriotism, and many more. Hadraawi did not just write, he was actively involved in the changes that took place in his society in his younger days. For daring to criticize the despotic government of Siad Barre in a play he composed, he was subjected to internment where he rejected inking an apology as the only condition for his release. Upon release, he fled to Ethiopia where he joined the Somali National Movement (SNM) and continued unleashing revolutionary poems. He would later refuse to seek asylum in the United Kingdom, and return to his homeland to singlehandedly lead a march (known as the “Hadraawi Peace March”) appealing for peace and an end to all animosities. Evidently, Hadraawi sees poetry not just as art, but also as a tool to be employed in changing the society for he did not only talk the talk—he also walked the walk. Herein lies his commitment as a poet to his people and society.

The collection placed under scrutiny is titled Maxamed Ibraahin Warsame “Hadraawi”: The Poet and the Man and it has seven of Hadraawi’s poems translated from Somali language to English by WN Herbert et al. The work is a commendable effort, although no one can argue that much of content and form has not been lost in translation.

“Society” is the first of the documented poem in the collection; it bespeaks the imminent fragmentation that was quickly engulfing the Somali society at the time of its composition. Hadraawi; in this poem; identifies lack of sagacity, blame, and greed as the major ills bedeviling his society; the resultant effect of these ills are therefore cowardliness, brutality, and disorderliness.

Wise council: you’re unobtainable!

Blame: you breed without bounds!

Greed: you are unbridled!

Brave horse: you’re hamstrung here!

Brute force: you bare your brainless face!

Sea of disorder: your full volume,

your ebb and flow, and breadth—

could I scoop you in this cup? (29)

The poem, “Society”, tells of societal disintegration, brothers fighting brothers, ballooning of trivial issues, irresponsibility and alienation on the part the political leaders, and finally lands on why the poet has chosen to pitch his tent with his people against the rulers; he punctuates every stanza with “would I be so at one with you?”.

You, the people, chose me:

you made your bed in my soul,

wrapped yourselves in my conviction,

used my heart as your pillow.

It’s you who make my lips move:

my fear at your fortunes,

my care at your conditions,

this is what matures me –

when someone defrauds you,

when you cry out for help,

a keen longing awakens my senses

and I begin to recite verse. (31)

Here, Hadraawi accepts that a poet is ordained to speak for his people, to be their voice; he sees their plight and seeks for them a better deal. He says again:

You, the people, chose me:

you granted me good fortune,

loaded me with luck:

if my brazenness burns like an iron

you bestowed that charisma on me;

you ordered me: be purposeful,

compelled me to battle for you.

If disasters hadn’t befallen you,

your best interests not been betrayed,

if your homeland hadn’t burned,

justice not been discarded,

the worth of schooling not belittled

being reduced to slogans,

would I be so at one with you? (31)

Hadraawi clearly intimates to us in the poem that the plight of his people is the muse fueling and propelling the fire of his poetry.

“The Killing of the She-Camel” is the second poem in the collection. Originally part of a play, this poem employs a variety of symbolic metaphors to depict the political situation in Somalia after the takeover by the military junta. Hadraawi cleverly adopts images of animals to hide his meaning in the poem—the result is a work that conveys the poetic ingenuity of the poet.

In the poem, the killing of a she-camel draws all from far and near who struggle to gobble down its meat. It is perhaps instructive to point out here that the camel is an important animal in the economic, social, and cultural lives of the Somali people; it is used as a means of payment (be it for bride price or as an atonement for wrongdoing), as a mode of transportation, and as food. In fact, a man’s wealth was formerly measured by the number of camels in his household. Now, keeping the she-camel alive is of much import for it is only this which guarantees procreation and continual supply of its milk which almost all Somalis consume as a beverage. But in this poem, we see the slaughtering of a she-camel with all rushing to get a share. No one thinks that the she-camel being alive is more important to the people than being dead. The she-camel here, therefore, represents the political wealth of the country while its slaughtering refers to the coup of Siyad Barre. Everyone wanting a share of the meat connotes the greed with which the junta and its friends plundered the country wealth and flaunted it— ”frying it in the glare of the sun”. Hadraawi also points out that there has been disgruntlement in the allocation of resources in the State in the third stanza. The poem comes with a refrain which is a pointer at the enormity of the task that the junta had taken upon itself; he sees them as the snake which “sneaks in the castle:/although it is carpeted with thorns”.

We see the poet reaffirming his commitment to his society and the struggle against bad leadership in the fifth stanza where he points out that he will neither be a part of their shenanigans nor stop producing the rallying cry until the day of judgment; he even went further to ask that he be tied to the task and never released.

Never will I ever accept

a single insulting slice

from those grasping commissars –

I won’t share a thing with them.

Until the grave’s is prepared

to forego its three-yard shroud

or a collar round the neck

since one at least is needed

to cover the naked dead,

I’ll keep rallying and calling

until the day of judgment,

pray my eyes can comfort the dead:

tie me to this task, and don’t

release me from its harness. (37)

Without mincing words, Hadraawi shows the level of his commitment towards the redemption of his society in the next poem titled “Clarity”. Composed as part of a write and response genre of poetry known as “Deelley” by Somalis, it captures Hadraawi’s refusal to admit defeat or be subdued in the fight against the powers that be, even after years of incarceration. He says:

I’ve still not admitted defeat

nor have I withdrawn:

that high inspiration,

that talent I was endowed with,

has not discarded.

…

When men dedicate to the struggle

and determine to fulfill their duty;

when they ready themselves for the charge,

amass the finest thoroughbreds;

when the reins are on the racers,

I never step aside.

With these words, Hadraawi affirms his pledge to the struggle, he shows that he is a man who abhors cowardice, and would not only write but be an active participant in the struggle towards liberation.

Hadraawi also uses the poem to address the utilization of tribalism cum clannishness to divide and rule the people by the political class thereby causing hostilities and discontentment among the populace. He vows to continue fighting against this social malaise of tribalism which was seeking to destroy his nation:

The clarion bell we carry will strike

destroying them like lightning,

those huggers of tribalism,

grubbers in money, who are everywhere

lusting to turn back

all hopeful development

and to despoil our nation –

I CAN’T LET THAT HAPPEN. [Emphasis mine] (41)

Lastly, Hadrawi calls for unity as the only path to peace and development as disharmony could only infer destruction:

Anyone who wants this life

to be serene,

to have savour and feel sound,

there is a path to follow:

people, you prosper

as one unit, as you share in

your shouldering of the burden –

that’s the only balm.

If it weakens in one wing

then its whole end is woe.

Is there any advice better than this,

any further examples you need

beyond this ample explanation,

or do you have something countering the case? (44)

In the stanza that follows this, Hadraawi passes the continuity of the poem to another poet and close friend of his, Maxamed Xaashi “Gaarriye”.

Among Hadraawi’s revolutionary poems documented in this collection, “Life’s Essence” remains a favorite for us. It shows Hadraawi to be not only a great poet but also a profound thinker. The profundity of his mind can be seen in the numerous pieces of advice he dishes out in the poem. Written in a popular western-style known as “dramatic monologue,” the poem reads like an original version of Rudyard Kipling’s “If”.

In “Life’s Essence”, Hadraawi addresses two characters whose voices we do not hear. The characters are Rashid and his daughter, Sahra. In reality, Hadraawi is addressing both the old and the younger generation of Somalis with Rashid representing the old whom had seen much carnage and destruction as a result of war, and Sahra representing the young and unborn generations of Somalis whom he hopes may survive the war and pick life’s lesson from it.

To Rashid, the poem persona tells the horrors of the battle at Sirsirraan. He tells him of the fouled air, the scattered bones, slaughtered corpses, the piercing groans, and the children wails. He concludes that the havoc is the result of decisions made rashly, decisions made in haste, a dearth of sagacity that only points at the destruction.

The poem persona praises Sahra’s beauty and lofty bearing as accustomed with “the women of the horn”, he tells her to be clean and retain her beautiful mien, he wants her to apply modesty in her doings, be succinct in her use of words and argument and be polite, and be contented with whatever she has, be respectful of older people and the Somali traditional values, remain docile in the face of injustice and persecution, not to join bandwagon, think outside the box, not to be discouraged in the face of adversities, love education, avoid war, never be afraid to challenge injustice, waste no time in condemning falsehood, and many more. Within, the lines of his numerous and profound advice of the poem persona lays the background of the ongoing war and the pain and havoc which comes with it.

This poem again shows Hadraawi’s patriotism and commitment to his people for the talks and calls for preservation of Somali values and mores while also denouncing war by preaching peace.

“Settling the Somali Language” was composed at the instance of making an official decree on the orthography of the Somali language. In the poem, Hadraawi conveys his happiness at finally settling a long disputation in what the official Somali script should appear like. In the refrain of the poem, we hear the poet pledging support and devotion to his mother tongue:

I must be devoted to Somali

develop through Somali

create within Somali

I must be rid of poverty

and give myself for my own mother tongue. (65)

The last two poems show a diversion from Hadraawi’s protest cum revolutionary poems, they bother on a subject which many poets have dwelt on before Hadraawi and will continue to deliberate upon after Hadraawi; here, we mean “love”.

The first of these poems is “Amazement”, a love poem which adopts the colorful and elegant language of metaphor to depict the beauty of the lover. Many believe this poem is the most famous of Hadraawi’s poems since it even has a musical rendition by a renowned Somali singer. For a revolutionary like Hadraawi, love is not a farfetched topic to reflect upon. You see, love is the opposite of hatred and war; hence Hadraawi’s love poems can be seen as a counter-reaction towards the hostility he came to witness in his society. Besides, the Somali society is replete with myriads of oral love poetry committed to memory in musical form. By harping on the love between a man and his lover, Hadraawi shows that he understands that the basic unit of society is family, and it is only when every man loves his woman and vice versa that the seeds of love can germinate and be cultivated in the society.

The last poem, “Has Love Been Ever Written in Blood!” has a true-life story tied to it. It revolves around a love letter written in the blood of the lover. This letter shocks Hadraawi and leaves him pondering what may happen when next the lovers meet, the enormity of such love and its sincerity. With the aid of a series of rhetorical questions, the poet openly calls out his thoughts on the nature of love.

Maxamed Ibraahin Warsame “Hadraawi” remains one of the greatest Somali poet and thinker. The musicality of his poetry (which unfortunately is lost in translation) composed in his native Somali language makes his poems easily committed to memory by the Somalis, and there have been musical records based on his poems. His poetry is filled with the flora and fauna of the Somali region as the images in his poems are woven via diction which reflects the mountainous terrain, animals, and trees present within his society. The use of metaphors, alliterative lines, and rhetorical questions adorns his poetry with elevated language. Albeit written in his mother’s tongue, the poems rival any best from the Western tradition, and it would not be a travesty to say Hadraawi’s poems even surpasses those of the Western tradition. However, Hadraawi’s is widely admired and revered not only for writing great epic and lyrical poems but also for standing up for his people, being their voice when it mattered and walking his talk. We may still not have answered the question of where the commitment of a poet should lie (is it to art, or to society?), but we have no doubts whatsoever of where that of Hadraawi’s lays. Hadraawi saw and used art for the betterment of his people and society.

We must not fail to commend the efforts of the translators (WN Herbert, Said James Hussein, Muhamed Hassan Alto, Martin Orwin, and Ahmed I Yusuf) without whom the work of this great poet (Hadraawi) would have remained in obscurity to many of us who have no access to the Somali language. Much may have been lost in translation, yet does the gain outweigh the loss indeed.

Thank you very much for reading, and let us meet again another time for a different discussion!

By Ubaji Isiaka Abubakar EazyBy Ubaji Isiaka Abubakar Eazy

RELATED:

The Literary Story Of Somaliland Has Been Muted By Hypocrisy

Our nation is renowned

Our nation is renowned

For its honesty, for humility;

Woven from a silken thread

Our people would harm no-one

Fearing Allah, their feelings

Are slow to stir – still,

They are not so easily duped

-Hadraawi

The story is told of a young Somaliland professional who left his country in the wake of its destruction by the dictatorship of Siyad Barre to look for greener pasture elsewhere. Our friend went to Europe where he would live for the next 25 years, serving as a civil servant in his new sanctuary, and as an Agricultural Economist consultant. When he returned home, he was always spotted with a hand luggage, presumably carrying a laptop. A Somalilander who had watched him for quite some time went to him and said, “my brother, where are you from?” “From Somaliland,” our friend cried.

“Are you sure?”

“I have been away for 25 years.”

“I see!!!”

“What?”

“Don’t worry so much about your bag; nobody will take it away from you!”

I left Somaliland for Kenya after a wonderful gesture of brotherly and sisterly love. I had been a guest at the 9th edition of the Pan-African-oriented Hargeysa International Book Fair, which ended on July 28.

On the morning of my departure, I had a quick interview with the founder of the book fair Prof Jama Musse Jama, a longtime friend, and Ghanaian writer Amma Darko. On my way to Egal International Airport, I realized that I did not have my phone. To cut the long story short, when I arrived in Nairobi, Prof Jama wrote me to say that I had left my phone at the residence hotel, and that he was sending it to Nairobi! So that is Somaliland. Why was I involved in these two incidents, first as a witness, and second as a protagonist? Ahoy! Every writer who aspires to completeness must give voice to the mute. The story of Somaliland is as fascinating, as it has been muted by the hypocrisy that pervades the world we live in today.

Long before the scramble for Africa that informed that coven-like gathering in Berlin, Sir Richard Burton had visited Somaliland in 1854 and described it as “a nation of poets.” Thus we have the extract at the beginning of this essay from the poetry of the legendary Somali poet Hadraawi. Notice in the poem the virtue of “honesty” and “humility.” Pick any of Hadraawi’s poems, Clarity, Life’s Essence, The Killing of the She-Camel, or Has Love Ever Been Written in Blood, and you will find yourself in the grip of one of the greatest living poets on earth today. Here is Hadraawi again:

Let these few lines be as striking

As the stripes of an oryx

As visible and as lovely –

I simply place them in plain view

Fragmented

When I met Hadraawi in 2012 in Djibouti I simply described the poet as “a legend.” Maxamed Ibraahin Warsame ‘Hadraawi’ served five years as a prisoner of conscience. When he was released, the British offered him political asylum. However, rather than turn the predicament of his country Somaliland into political merchandise, Hadraawi declined to take the offer. When I published my Hadraawi essay, Egyptian writer Ekbal Baraka said, “Thank you for introducing this great Muslim poet. It is a shame that we in the Arab world do not know about him!” Ekbal took the trouble to translate my essay into Arabic.

The story of the great poet and his homeland is not only unknown in the Muslim world, but to all of us. This brings us to the thrust of this essay as summed up in the title: Literature and Somaliland’s Quest for International Recognition. In 1885 European countries convened in Germany and curved Africa into their spheres of influence. The Somali nation is a classic example of that “scramble” that Kenyan writer Shadrack Amakoye Bulimo has described as the height of “idiocy.”

The Somali-speaking people were fragmented into five different regions: Kenya, Ethiopia, Djibouti, Somalia, and Somaliland. The last three became French, Italian, and British colonies respectively. Of the five Somali-speaking territories, British Somaliland – whose capital city is Hargeysa – was the first to gain independence from Britain on June 26, 1960, (long before Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania). Four days later Somalia Italiana – whose capital city is Mogadishu – was granted independence and on July 1, 1960 the former British and Italian colonies merged. It was a disastrous marriage from the word go, but which was compounded by Siyad Barre’s bloody military coup d’état in 1969.

For the people of Somaliland, Siyad Barre’s rein was synonymous with a programme of killing, maiming, annihilation, bombing of physical spaces, towns, villages, homes, markets, a “genocide” yet unspoken about as cultural activist and intellectual Zahra Jibril observes in an interview. One needs to read the prison memoirs of Mahamed Barud Ali, The Mourning Tree, to sense that mayhem and brutality. In 1982 Somalilanders started a guerrilla warfare that in 1991 drove Siyad Barre out. It was then that Somaliland traditional leaders convened a meeting to deliberate on the destiny of their people.

On May 18, 1991, the Republic of Somaliland announced it had reclaimed its lost independence and thus severed links with Somalia Italiana. The country’s top ranking diplomat, the Foreign Affairs Minister, Dr Saad Ali Shire in a lecture, The Building Blocks of a Nation, and in a subsequent interview said the priority was to begin rebuilding the destroyed lives of people and put in place a framework for the nation’s regeneration. Twenty five years later, like the phoenix, Somaliland is alive, thriving, beautiful, and peaceful. The country has secured its borders, is able to maintain peace, has a functioning parliament, a trusted judiciary, a disciplined military, a dutiful police service, a central bank with its own currency, and above all, an admirable democracy where we have had an incumbent president losing elections at the ballot with just 80 votes, and peacefully handing over “power” to his fellow countryman!

This is the Somaliland the world has ignored and continues to postpone her recognition preferring instead to pumper tyrants, prop failed states, and support undemocratic regimes in Africa. Somaliland exposes the insolence of the West. Somaliland mocks the puppet leadership of Africa.

South Africa and Rwanda have pushed for Somaliland’s recognition, backed by AU’s own fact-finding missions. But as international lawyer Quman Jibril says, her country may have fulfilled the legal requirements for recognition, what is lacking is political goodwill from African leaders.

At this year’s book fair the theme was leadership and creativity and Ghana was the guest country. Africa is crying for a visionary and inspiring leader. In Somaliland, I visited the staggeringly beautiful rock art at Las Geel. There are 149 sites of these exquisite rock caves with paintings and writings about domestic and wildlife, people, farm and war tools. The rock paintings of Las Geel are an affirmation of life and a celebration of art dating 10,000 years ago. Yet UNESCO refuses to listen to pleas of Somaliland for protection of this world heritage site. So this is the homeland of Hadraawi!

By Khainga O’Okwemba

-The writer is the President of PEN Kenya Centre, a poet, journalist and essayist

Source: The Standard