Somaliland became the latest country to switch off the Internet to prevent exam leakage and cheating

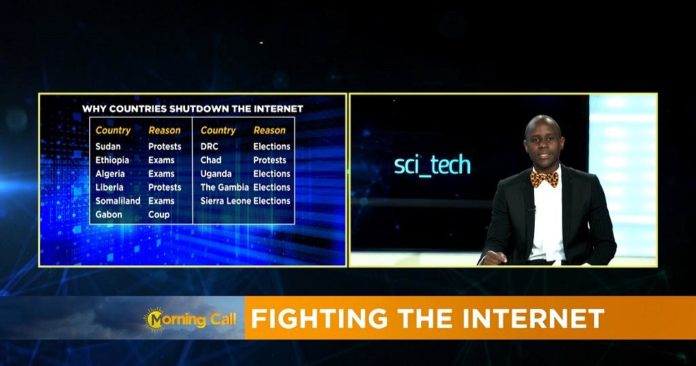

Over the past one week, governments in Sudan, Ethiopia, Algeria, Liberia, Venezuela and Kazakhstan have disrupted internet access for their citizens, continuing what is fast becoming a popular tool for repressing dissenting voices.

Somaliland on Tuesday became the latest African nation to direct internet service providers to switch off the internet, arguing that the move was designed to curb exam leakages.

Over 188 shutdowns were recorded globally by Access Now in 2018, up from 108 in 2017 and 75 in 2016.

Why do countries block the internet?

Ethiopia, The Republic of Congo, Algeria and now Somaliland have restricted internet access during national exams.

Chad which has implemented a social media blackout for over a year now claims applications like Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp have helped to organize anti-government protests and threatened internal security.

Other countries that have restricted the internet to curb protests include Ethiopia, Cameroon, Zimbabwe, Sudan, Algeria and Togo.

Gabon briefly switched off the internet during an attempted coup early this year, while elections have been one of the most common periods when the internet is likely to be restricted. Governments in Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda, The Gambia and Sierra Leone have all shut down the internet during elections.

Counting the cost

While the government temporarily achieves its objective of restricting the flow of information during internet blackouts, activists have argued that it comes at a great cost.

Netblocks, an NGO that monitors internet censorship said Ethiopia lost up to $17m during the four days the internet was off last week.

In 2017, the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA), estimated that internet shutdowns in Sub-Saharan Africa had cost the region up to $237m.

Beyond Africa, the Brookings Institution, a think-tank, said the global economy lost $2.4bn through internet shutdowns between 2015 and 2016.

An expert’s take

We talked to Alp Toker, the Executive Director of NetBlocks, to share with us insights gained from their work of asking governments to keep the internet on.

What are the most common ways of executing internet shutdowns?

Most commonly, social media messaging applications are restricted. This means that some services are still available, and the goal is to stop people from posting messages online. But we also do see full shutdowns. There is also throttling, the slowing down of internet access. This is designed to evade detection.

How do citizens bypass shutdowns, which has been reported as the most common reaction to such government action?

If its a social media block, then you can use Virtual Private Networks or VPNs to circumvent them. Unfortunately, authorities are also wisening up to this, so once people start to use VPNs, authorities shut down the internet. And when connection is down, there is nothing you can do. It is actually impossible to circumvent a total internet blackout.

Going forward, what can be done to preserve freedom of expression in the face of increasing internet shutdowns?

The first step is to actually map it out to understand the extent. Shutdowns have happened for many years, and we didn’t know how many were happening, we didn’t know how often they were happening. Now, with projects like Netblocks, its possible to actually get a full map of this. And now we can how widespread this, we can actually start to push back, we can build policy. We need the UN to engage, we need the African Union to engage, we need the people to speak up, because if the people don’t speak up, then they will lose their voices, and once those voices are gone, it will be very hard to regain them.

A bleak future?

While governments usually order network operators to block particular websites and corresponding Internet Protocol (IP) addresses, Daniel Mwesigwa, a technology analyst in Uganda says the authorities are getting more sophisticated.

‘‘In more recent times, governments have used sophisticated methods such as Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks where a network is flooded by bogus which causes it to fail,’‘ Mwesigwa told Africanews.

Mwesigwa adds that Uganda’s social media tax introduced in July 2018, amounts to an internet shutdown, since Ugandans are blocked from accessing over 50 OTTs including social media unless they pay a tax of USD 0.05 per day of access.

‘‘In June 2018, a month before the introduction of the tax, the internet penetration rate in Uganda stood at 47.4% (18.5 million internet subscriptions) but three months later, it had fallen to 35% (13.5 million), according to data from UCC.’‘

Mwesigwa believes that measuring the impact of internet shutdowns through tools like Netblocks can influence policy development ‘promote freedom of expression online especially in (semi-) autocratic dispensations’.

By Daniel Mumbere