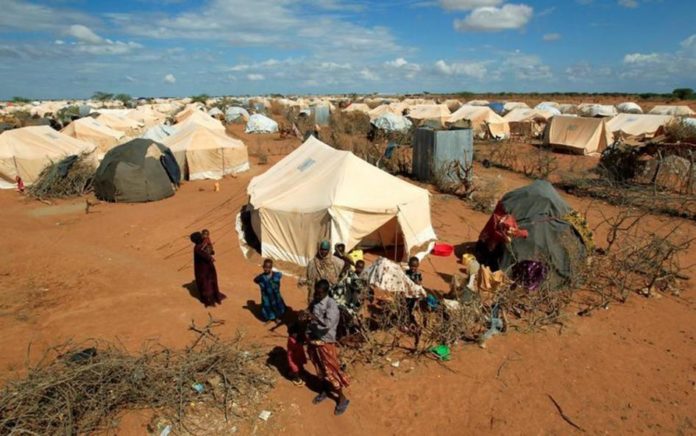

The Kenyan government should abandon a renewed push to close the enormous Dadaab refugee camp, Human Rights Watch said today. The move threatens the rights and safety of 250,000 people, mostly Somali refugees and asylum seekers, whose future is now in limbo.

“Kenya should abandon plans to close the camp and instead uphold its commitment to protect refugees it has hosted for three decades,” said Otsieno Namwaya, Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. “The authorities should ensure that any refugee returns are voluntary, humane, and based on reliable information about the security situation in Somalia.”

On February 12, 2019, Kenyan authorities, citing security concerns, sent a note to the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) about plans to close Dadaab refugee camp, home to nearly a quarter of a million people, within six months, according to a leaked internal UN document. The note instructed UNHCR “to expedite relocation of the refugees and asylum-seekers residing therein.”

The internal document says that between December 2014 and the end of 2018, UNHCR had helped the government return 82,840 refugees to Somalia under a voluntary repatriation program. However, the number of returnees dropped to just 7,543 in 2018 as compared with 33,792 in 2016 and 35,409 in 2017. Most of those who returned in 2016 and 2017 were refugees who had fled Somalia in the aftermath of severe drought in 2011.

On February 28, the leaked document said that UNHCR responded saying Kenya’s options include voluntary repatriation of refugees to countries of origin, if safe to return; relocation of refugees to other parts of Kenya; social integration in Kenya of refugees with family links to Kenyans; or resettlement to third countries.

This is not the first time Kenya has announced plans to close Dadaab. On May 6, 2016, Dr. Eng Karanja Kibicho, then the Interior Ministry’s principal secretary, announced that the government would no longer host refugees and was disbanding its Department of Refugee Affairs, which processes refugee registration, leaving 12,000 asylum seekers who remain undocumented. He also said the government would close refugee camps “within the shortest possible time” because of national security concerns.

In February 2017, the High Court ordered a halt to plans to close Dadaab and ruled that any such plans were unconstitutional and violated Kenya’s international obligations.

The reason for the latest communication to UNHCR is not clear. Despite the government’s frequent statements that Somali refugees in Kenya are responsible for Kenya’s insecurity, officials have never provided evidence linking Somali refugees to any terrorist attacks in Kenya. Nevertheless, Kenyan police have targeted Somali refugees and ethnic Somali Kenyans in discriminatory and abusive law enforcement operations, such as mass arrests and round-ups during what it called Operation Usalama Watch in 2014.

“Many Somali refugees are themselves victims of violence, from which they fled to seek protection,” Namwaya said. “Forcing them to go back to face violence or persecution would be inhumane and a violation of Kenya’s legal obligations.”