Ethiopia is building a mighty dam on the Blue Nile, promising economic benefits for both itself and Sudan. But Egypt fears for its freshwater supply. The parties should agree on how fast to fill the dam’s reservoir and how to share river waters going forward.

What’s new? Ethiopia is moving ahead with construction of Africa’s largest dam, despite Egypt’s worry that it will reduce the downstream flow of the Nile, the source of around 90 per cent of its freshwater supply. It is crucial that the parties resolve their dispute before the dam begins operating.

Why does it matter? The Nile basin countries could be drawn into conflict because the stakes are so high: Ethiopia sees the hydroelectric dam as a defining national development project; Sudan covets the cheap electricity and expanded agricultural production that it promises; and Egypt perceives the possible loss of water as an existential threat.

What should be done? The three countries should adopt a two-step approach: first, they should build confidence by agreeing upon terms for filling the dam’s reservoir that do not harm downstream countries. Next, they should negotiate a new, transboundary framework for resource sharing to avert future conflicts.

Executive Summary

The three-way dispute among Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan over the sharing of the Nile waters remains deadlocked. An April 2018 leadership transition in Ethiopia eased tensions between Cairo and Addis Ababa. But the parties have made little headway in resolving the crisis triggered by Ethiopia’s 2011 decision to build the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), expected to be the largest hydropower plant in Africa. Egypt fears that the dam will drastically reduce water flow downstream and thus imperil its national security. Ethiopia and Sudan assert their right to exploit the Nile waters to further develop their economies. The three countries need to act now to avert a graver crisis when the dam comes online. They should accede to immediate steps to mitigate damage, particularly during the filling of the dam’s reservoir, when water flow to downstream countries could decline. Next, they and other riparian states should seek a long-term transboundary agreement on resource sharing that balances the needs of countries up and down the Nile basin and offers a framework for averting conflict over future projects.

The stakes in the dispute are high. Egypt relies on the Nile for about 90 per cent of its freshwater needs. Its government argues that tampering with the river’s flow would put millions of farmers out of work and threaten the country’s food supply. In Ethiopia, engineers estimate that the GERD will produce about 6,450 megawatts of electricity, a hydropower jackpot that would boost the country’s aspirations to attain middle-income status by 2025. Authorities have sold the dam as a defining national endeavour: millions of Ethiopians bought bonds to finance its construction, helping implant the initiative in the national psyche. Fervent public support for the dam has recently cooled, however, following allegations of financial mismanagement.

Between 2011 and 2017, Egyptian and Ethiopian leaders framed the GERD dispute in stark, hyper-nationalist terms and exchanged belligerent threats. Politicians in Cairo called for sabotaging the dam. Media outlets in both countries compared the two sides’ military strength in anticipation of hostilities.

A recent rapprochement has quieted the row. Ethiopia’s new prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, visited Cairo in June 2018 and promised to ensure that Ethiopia’s development projects do not harm Egypt. In turn, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi said his country recognises that the dispute has no military solution. But despite the warming relations, there has been little substantive progress toward a resolution.

Political upheaval in all three countries complicates this task to varying degrees. In Sudan, President Omar al-Bashir, in power since 1989, is clinging precariously to his job amid the most sustained wave of protest the country has seen in decades. In Ethiopia, Abiy, while enormously popular with the public, is struggling to consolidate his hold on power. Egypt’s Sisi is relatively secure in his position, but his drive to extend his stay in office until at least 2034 has divided the military establishment, his key domestic constituency. These internal dynamics mean that the leaders dedicate less time to the Nile dam issue than they should. They could blunder into a crisis if they do not strike a bargain before the GERD begins operation.

Egyptian, Ethiopian and Sudanese authorities should consider a phased approach to agreeing on a way forward. Most urgent is the question of how quickly to fill the dam’s reservoir. At first, Ethiopia proposed filling it in three years, while Egypt suggested a process lasting up to fifteen. To achieve a breakthrough on this question, Ethiopia should fully cooperate with its downstream partners and support studies seeking to outline an optimal fill rate timeline. If necessary, the three countries should seek third-party support from a mutually agreed-upon partner to break the impasse. Ethiopia should also agree to stagger the fill rate so that it picks up pace in years with plentiful rains, which would minimise disruption of water flows.

To reduce mutual suspicion, leaders should take a number of confidence-building measures. Prime Minister Abiy should invite his Egyptian and Sudanese counterparts to tour the GERD construction site, thus highlighting Ethiopia’s willingness to address downstream countries’ concerns. Such a demonstration of Ethiopian good-will could afford the Egyptian authorities the space to make necessary adjustments, notably improving inefficient water management systems. For its part, Cairo should declare that it will not support armed Ethiopian opposition groups, to allay Addis Ababa’s fears.

Outside partners should encourage Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan to approach the dispute not as an existential conflict but as a chance to establish a resource-sharing partnership.

Outside partners could help build confidence. The European Investment Bank, which the Ethiopians perceive as less pro-Egyptian than the World Bank, might offer Addis funding for the last phase of dam construction. Such funding could be conditional on Ethiopia cooperating on sticking points such as the fill rate. The EU should continue its talks with downstream countries on potential guarantees (including loans) and other instruments to support those countries in years in which drought or other shocks endanger food security. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), as well as Qatar and Turkey, could offer bilateral or trilateral investment in agriculture in Ethiopia and/or Sudan that afford Egypt a discounted and reliable supply of staples, notably wheat and rice. The U.S. and China, which enjoy close ties to some Nile basin governments, could also encourage parties to resolve their disputes before the GERD is completed.

Next, authorities in Addis Ababa, Cairo and Khartoum should lay the ground for more substantive discussions of a long-term framework for Nile basin management to avert similar crises in the future. Egypt should rejoin the Nile Basin Initiative, the only forum that brings together all riparian countries and the best venue available for discussing mutually beneficial resource sharing. Such talks would consider Egyptian proposals that, in the future, upstream countries carry out major development projects in consultation with downstream nations. A permanent institutional framework could also help the countries prepare for challenges down the road, including climate change-induced environmental shocks, notably variable rainfall patterns, which could cause greater water stress.

Outside partners should encourage Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan to approach the dispute not as an existential conflict but as a chance to establish a resource-sharing partnership. Delays in the GERD’s completion and the improved mood following Prime Minister Abiy’s ascent make this moment propitious for negotiating a way forward. Waiting until the dam is operational – when its impact on downstream countries is clearer – would raise the risk of violent conflict.

Nairobi/Abu Dhabi/Istanbul/Brussels, 19 March 2019

I.Introduction

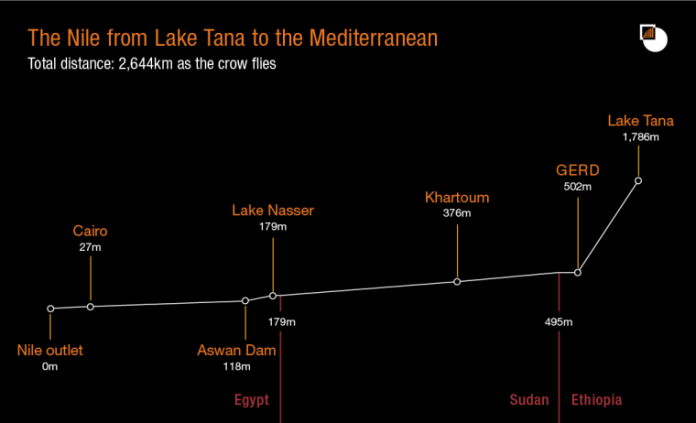

One of the world’s longest rivers, the Nile cuts through eleven African countries with a combined population of 437 million. From headwaters in the Ethiopian highlands (for the Blue Nile) and the Great Lakes countries of Rwanda and Burundi (White Nile), the river’s two main branches merge at Khartoum, the Sudanese capital, before flowing north through Egypt and finally into the Mediterranean Sea. The Blue Nile, the larger of the two branches, accounts for most of the river’s water flow into Sudan and Egypt, with two other branches, the Tekeze-Atbara and the Baro-Akobo-Sobat, also draining the Ethiopian highlands. In total, some 84 per cent of the Nile’s water flow originates in Ethiopia. For centuries, the Nile basin’s inhabitants have tapped the river for hydropower, fish and drinking water, as well as used it for recreation and tourism. Most critically, though, they have drawn upon it to irrigate farmland.

The Nile carries relatively little water compared to the world’s major rivers. Its volume is only 5 per cent of the Congo River’s, for example. As populations grow and climate change makes water supply increasingly erratic, geopolitical battles for control of its waters, always a factor in shaping relations among riparian countries, have grown fiercer.

For centuries, Egypt has enjoyed virtually unrestricted use of all the river’s water. British colonial authorities helped codify its status as the Nile waters’ principal beneficiary in treaties they negotiated on behalf of Egypt and Sudan in 1902 and 1929. In 1959, Egypt and newly independent Sudan concluded a bilateral agreement that essentially ratified the terms of the previous two. As a desert agricultural country – the Greek historian Herodotus famously called it “the gift of the Nile” – Egypt is heavily reliant on these waters. For years, it has assumed an aggressive posture to protect the security of its water supply and to prevent projects upstream that could hinder water flow. As former Egyptian president Anwar al-Sadat said in 1978: “We depend upon the Nile 100 per cent in our life, so if anyone, at any moment, thinks of depriving us of our life we shall never hesitate to go to war”. Sudan also depends on the Nile, albeit to a lesser degree.

Ethiopia has long objected to this state of affairs, seeing the colonial-era treaties as lopsided, and aspired to exploit the river to expand its own economy. Ethiopia disowns the 1902 treaty as a relic of its monarchical past, and has never recognised the latter two agreements, about which it was not consulted.

In this light, Ethiopia’s surprise announcement, on 30 March 2011, that it planned to construct a large dam, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), on the Blue Nile caused considerable consternation in Cairo and Khartoum. Both downstream countries reacted immediately and furiously, demanding that the project be frozen. Since then, the GERD has been the centrepiece of the Nile waters dispute. The three parties’ relative geopolitical heft has shifted, and Sudan has reversed its opposition to the dam, but the basic dynamic remains the same: Ethiopia wants the GERD for hydroelectric power and industrial development, while Egypt fears the project will reduce its water supply. Sudan, on the other hand, hopes the dam can help it substantially expand agricultural production by better regulating annual floods. As the GERD’s construction continues apace, reaching agreement on the management of Nile waters, particularly on how quickly Ethiopia will fill the project’s reservoir, is critical.

This report outlines the main actors’ perspectives on the dispute and explores how they can reach such an agreement. It proposes that parties focus first on settling the GERD crisis to defuse tensions before the dam comes online. It suggests that the parties go on to negotiate a comprehensive transboundary resource management agreement, involving other riparian states, that could both ease tensions over the dam and include a lasting basin-wide settlement for resource sharing. The report is based on interviews conducted from April to November 2018 with a wide range of water experts, political and security analysts, government officials and diplomats in Addis Ababa, Cairo and Khartoum, as well as Nairobi, Kampala, Abu Dhabi, Riyadh, Doha, Ankara, Istanbul, New York and Washington.

II.Ethiopia and the GERD

Addis Ababa has long contested Egypt’s claims of hegemony to the Nile waters, which were outlined in the series of treaties brokered by the British.

Addis Ababa has long contested Egypt’s claims of hegemony to the Nile waters, which were outlined in the series of treaties brokered by the British. A statement Ethiopian authorities sent to the Egyptian government in 1958 summed up their view. Ethiopia, it said, “may be prepared to share this tremendous God-given wealth of hers with friendly neighbour nations [but] it is Ethiopia’s sacred duty to develop the resources it possesses in the interest of its own rapidly expanding population and economy”.

Plans for a dam on the Blue Nile date from around the same time. The United States Bureau of Reclamation identified a site in geological surveys conducted between 1956 and 1964. Decades of strife including a long civil war and wars with neighbouring Somalia and Eritrea – as well as Egypt’s strength on the world stage – made it impossible for Ethiopia to advance this objective for almost a half-century. Only with the extended period of economic development and relative political stability under Prime Minister Meles Zenawi could planning for such a dam proceed. His government made plans in secret for some years before going public with the announcement in 2011. Most Ethiopians regard the project as a source of national prestige and millions have invested their own funds in its construction. It “brings together all the diverse sections of society”, said a think-tank official. “The haves and the have-nots, the young and the old, women and men, locals and those in the diaspora; all came together to mobilise financing for the dam”.

Still a work in progress, the dam is located approximately 700km north west of the capital Addis Ababa and 40km from the border with Sudan. It is sandwiched between two hills, with its twin power stations positioned on either side. Upon completion, the GERD is expected to be the largest dam in Africa, 1,800m long and 145m high, with a capacity to generate 6,450 megawatts of hydropower. At the height of construction about 12,000 people were employed at the site, working in shifts around the clock.

In the third week of February 2019, Ethiopia Electric Power, Ethiopia’s power utility, announced that it had contracted two Chinese firms to handle the pre-commissioning phase of construction, which is expected to be completed by 2022. According to the country’s water minister, the dam will first be able to generate electricity at the end of 2020. Past Ethiopian projections of when the dam will come online, however, have proven overly optimistic. At first, the dam was slated to begin operations in 2017, but administrative and financial problems delayed its completion. The current delay offers a window of opportunity for parties to reach some form of agreement on how to manage the dam’s impact on water flows. Waiting until the GERD is operational will raise the risk of conflict due to the high stakes at play, particularly for Egypt, with its heavy dependency on the Nile for freshwater.

A.Meles Zenawi and Ethiopia’s Project X

Planning for the GERD in Meles’s inner circle began around 2006. The government ordered updated site surveys, which were conducted between 2009 and 2010, and engineers submitted a dam design in November 2010. The prime minister’s office directly coordinated preparation for what was then known as Project X, carrying it out in extreme secrecy. Ethiopia handed the leading role in the dam’s construction to the Italian firm Salini Impregilo. The project was partially coordinated by the Metals and Engineering Corporation (METEC), a military-led industrial conglomerate, thus classifying the endeavour as a matter of national security.

A number of factors informed Meles’s decision to build the dam. The project was an integral part of his 2010-2015 Growth and Transformation Plan, which aimed to create large-scale foreign investment opportunities, quintuple power generation from 2,000 to 10,000 megawatts, cultivate a more dynamic manufacturing sector, and significantly expand road and rail infrastructure. The GERD was a natural outgrowth of Meles’s vision to shape a state for which economic growth was an “absolute and overriding priority. Development should be a matter of national survival; the ideology should be that growth is survival”.

In this light, Meles saw the GERD as an ambitious project that would symbolise Ethiopia’s efforts to achieve middle-income status. Sales of electricity produced by the GERD would be a key source of hard currency. Despite Meles’s huge efforts to establish industrial parks and create enabling infrastructure, exports lagged – and still lag – behind imports by a large margin. Ethiopia has long struggled to obtain enough hard currency to buy the imports that it needs.

Meles’s motives were also political. After the contested 2005 election, in which the opposition made impressive gains, he increasingly relied on repression to sustain his grip on power. The government thought that uniting the public behind a grand national endeavour would strengthen its hand. When Meles announced the GERD’s ground-breaking in March 2011, he added that Ethiopia would seek no external finance for the initiative. The government launched a massive nationwide fundraising campaign. Millions, including many peasant farmers, contributed, as the project attracted widespread support. “Every country must have one large defining project. This is our Hoover Dam”, said one Meles adviser, citing the giant American dam. The project drew widespread support from the masses, though many elites at home and in the diaspora were more sceptical.

Lastly, the prime minister saw the project as crucial for gaining leverage in the region. Ethiopia had lost direct access to the sea after Eritrea became independent, and it had frozen relations with Asmara since fighting a bitter war with Eritrea from 1998 to 2000. Addis perceived exporting electricity to countries with insufficient generation capacity of their own as a way to wield regional clout. Controlling the Nile’s flow would be another unspoken source of influence. Most critically, Meles viewed the GERD as fulfilling long-nursed Ethiopian ambitions to upend Egypt’s historic position as Nile basin hegemon. By gaining control of the flow of the river, his team calculated, Addis Ababa would gain considerable geopolitical clout. To cultivate greater continent-wide support for the dam project, Meles lobbied African leaders to endorse the initiative. The African Union adopted the dam as a flagship project and assigned its infrastructure unit, the Program for Infrastructure Development in Africa, to support the dam’s construction.

While no one faults Ethiopia for desiring to use its hydrological resources to further expand its economy, some experts assert that the Meles administration made a number of mistakes in its conception and execution of the project. Looking to achieve geostrategic goals, notably ending Egypt’s hegemony over the Nile, Ethiopia settled on a dam design featuring a huge reservoir, bigger, some experts contend, than what was needed for a dam intended to generate hydropower rather than to store water for irrigation. The large reservoir gives Ethiopia the capacity to regulate the river’s downstream flow to Egypt and Sudan, but this control comes at a cost. The dam’s design means that the GERD can operate at peak capacity only during the few months in the year when rainfall is highest in the Ethiopian highlands. Some experts estimate that the dam will attain peak capacity only 28 per cent of the time. Also, the extreme secrecy with which the project was managed meant that Ethiopia could not benefit sufficiently from external technical support, resulting in both a sub-optimal design and a more expensive project.

For some time after Meles made the GERD public in 2011, its construction proceeded undisturbed; Egypt and Sudan both initially resisted the project, but each was embroiled in domestic turmoil (see Sections III and IV). In August 2012, however, Meles died, prompting a period of upheaval in Ethiopia itself that intruded upon construction. The late premier had dominated all branches of government. His passing ushered in a power struggle that distracted policymakers from the single-minded focus he had maintained upon the dam’s construction. Accompanying this political upheaval was growing corruption, including within the security sector, which was leading dam construction. METEC, the military-run conglomerate and lead domestic contractor for the GERD, became a focus of controversy amid allegations of graft and mismanagement.

The power vacuum created by Meles’s death, perceptions of ethnic exclusion particularly among the Oromo, the country’s biggest ethnic group, and frustration over an economy unable to absorb millions of unemployed youth contributed to social unrest. Increasingly, the regime had to focus on self-preservation rather than projects such as the GERD. Street protests began in 2015, and lasted until the resignation of Meles’s successor, Hailemariam Desalegn, in February 2018. At no point did dam construction stop during the period of political upheaval, but it did proceed at an uneven pace.

B.Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and the GERD

Ethiopia’s new prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, has striven to put the dam project back on track, though some in the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) question his commitment to it. Abiy was elected head of the EPRDF in April 2018 at the conclusion of a two-month party congress. Since then, he has governed boldly, striking a peace deal with Eritrea, releasing political prisoners, welcoming back exiled opposition leaders, appointing a slew of women to key positions and vowing to open up political space. But he faces enormous challenges. Ethnic tensions are mounting in much of the country, with militias proliferating, violence reaching levels not seen in decades and leaders in ethnic federal states demanding greater autonomy. How Abiy will keep these forces in check, particularly with elections looming in 2020, remains unclear. Moreover, his replacement of leaders in the security forces and crackdowns on old-guard figures accused of corruption appear to have generated hostility to his rule among elements of the bureaucracy and security establishment.

Many Ethiopians view the GERD as a critical plank of such an economic revival platform.

Abiy also needs reforms that can breathe new life into the economy and create jobs for millions of unemployed youths whose frustrations have spilled into the streets. Many Ethiopians view the GERD as a critical plank of such an economic revival platform. Upon completion, the dam would go some way toward addressing chronic energy shortages, particularly in the industrial sector, and earning hard currency for the treasury. It would help many rural households switch to cleaner forms of energy.

Abiy signalled the dam’s ongoing importance when he toured the construction site just weeks after taking office in the company of Simegnew Bekele, the lead engineer. On 26 July, however, the project suffered a fresh setback when Simegnew was found dead of a gunshot wound in his car in the capital’s busy Meskel Square. Simegnew was the figure most closely associated with the dam, and his impassioned media appearances explaining the GERD’s potential benefits had made him a much-loved figure across the political spectrum. Hundreds took to the streets in his hometown Gondar, as well as in Addis Ababa, to mourn him. The media speculated feverishly about possible foul play, but police eventually ruled his death a suicide. In late August, at his first press conference, Abiy fielded questions about the state of the GERD project. He accused METEC of failing the country and announced that the firm would play no further role in dam construction. On 12 November, police arrested 63 METEC officials for alleged involvement in corruption.

It is unclear whether METEC’s removal from the project will speed up work on the dam, or how much work remains, because construction still proceeds in secret. Ethiopian authorities claim that the dam is 60 per cent complete, and Western diplomats who have visited the site say much of the physical infrastructure is finished. That said, complex tasks remain pending, particularly the construction and installation of the turbines and generators, which Ethiopia has outsourced to Chinese firms China Gezhouba Group and Voith Hydro Shanghai. In addition, due to foreign currency shortages at home, Ethiopia badly needs extra funding to pay for the final phases of construction and to settle bills owed to the main contractor.

Abroad, Abiy has shown greater sensitivity than his predecessors to the concerns of downstream countries Egypt and Sudan. He is notably friendlier to Egypt, at least in public. Cairo cheered his June 2018 decision to send the two most powerful figures in the security forces – intelligence head Getachew Assefa and armed forces chief Samora Yunus – into retirement; it viewed both men as harbouring hardline positions on the Nile waters dispute. Abiy has also repaired ties with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Riyadh and Abu Dhabi are among his most prominent external supporters and both have supplied funding to help stabilise Ethiopia’s struggling economy.

Abiy enjoys a number of advantages over his predecessors in GERD-related diplomacy. First, the project is identified with the Tigray People’s Liberation Front, the component of the ruling party that dominated previous administrations. Since he took office Abiy has tried to distance himself from this group’s legacy, for instance criticising aspects of their management of the dam project. In doing so, he has created wiggle room for compromises with downstream partners, which he can sell as correction of his predecessors’ mistakes. Secondly, Abiy has cultivated better ties with Cairo, Addis Ababa’s historical rival, and its allies in Riyadh and Abu Dhabi. To this end, he might be better placed to ask Egypt to offer concessions of its own in exchange for greater Ethiopian cooperation.

The more convivial environment notwithstanding, Abiy clearly intends to complete the GERD. Indeed, he has little choice but to do so, if only because many Ethiopians regard the dam as indispensable for national development. If Abiy has changed the tone of Ethiopia’s Nile diplomacy, he has not altered the bottom line.

C.Cooperation Mechanisms

Given that dam construction continues apace, it is urgent that the three main parties seek agreement on how to manage its impact. They should also pursue long-term accords for sharing the Nile waters. A venue is already in place for the two sets of negotiations – but each needs an infusion of diplomatic energy.

The most active negotiations over the GERD have taken place in tripartite talks involving Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan. The talks kicked off in 2011, soon after the announcement of the GERD, when the parties formed a trilateral joint technical committee to discuss a way forward. The parties notched an important achievement on 23 March 2015, when they endorsed a “declaration of principles” for resolving the dam crisis. The document calls on all sides to “cooperate based on common understanding, mutual benefit and good faith” and to take steps that prevent “significant harm” in using the Blue Nile.

This language, anodyne as it sounds, represented a significant compromise by all sides. In accepting that the three countries should share the Nile waters on the basis of “mutual benefit”, Egypt dropped its wholesale opposition to major upstream projects on the Nile and its demand that Ethiopia halt the dam’s construction. Sudan likewise signalled a more flexible position on upstream water use. And by committing to prevent “significant harm” with the dam project, Ethiopia, too, made a notable concession, namely that it needed to take the concerns of downstream countries into account.

Negotiators have made little headway since the declaration of principles, however, despite regular meetings. In 2011, Ethiopia rejected an Egyptian proposal that it suspend dam construction pending impact studies. Ethiopia also turned down an Egyptian request that it revise the dam’s design to incorporate four extra spillways that would guarantee the continuous flow of water in the event that the primary floodgates malfunctioned. Ethiopia, in turn, accused Egypt of negotiating in bad faith while forging alliances with its erstwhile nemesis Eritrea and hostile elements in Somalia and South Sudan.

Egypt blames the Ethiopian authorities’ persistent refusal to cooperate with requests for independent studies of the dam’s impact for the lack of progress. In Cairo’s eyes, Addis Ababa has consistently played for time, stringing talks along even as it continues with construction. Egypt claims that this attitude reflects Ethiopian fears that an independent study would fault Addis Ababa’s approach to the GERD project’s management and thus tie its hands. “Ethiopia doesn’t want anything that publicly endorses our position to come to light. They will block anything that proves our position, and our concerns”. Ethiopia disputes this and accuses the Egyptians of seeking to block the project from the start.

The gap between what Ethiopia hopes for and what Egypt in particular would accept remains wide.

With Abiy in power, the tripartite talks could be more fruitful, as Ethiopia is displaying greater flexibility than in the past. When the three countries signed the declaration of principles, their respective security agencies had no open lines of communication, despite wielding great influence over policy (Ethiopian and Egyptian military and intelligence agencies had essentially cut off contact in 1995, following an assassination attempt on then President Mubarak in Addis Ababa). Throughout 2017, European diplomats strove to remedy this problem, pressing all sides to send security officials to talks. They achieved partial success with the January 2018 round: Egypt sent high-ranking security chiefs, even as Ethiopia delegated junior security officials. Abiy has changed this practice. He assigns senior security officials to take part in talks alongside officials from the foreign and water ministries.

The gap between what Ethiopia hopes for and what Egypt in particular would accept – particularly on the immediate issue of the pace at which Ethiopia fills the dam’s reservoir – remains wide. But it nonetheless appears bridgeable. All parties reportedly accept the need to strike a compromise between Ethiopia’s initial desire to fill the dam in three years and an Egyptian proposal that the reservoir be filled in fifteen.

In the second week of May 2018, the intelligence agency heads of the three countries, along with the foreign and water ministers, held talks on this subject and set up a committee including experts from the three countries to agree upon a way forward. The National Independent Research Study Group, as the team they formed was called, mirrors a 2013 attempt to determine a mutually acceptable fill rate. Cairo, Addis Ababa and Khartoum should take steps to ensure that whatever decision emerges from this latest round sticks. Ethiopia should accept that the findings of the study should be binding. To build confidence, the three parties should appoint a third party to help guide the process and formulate technical proposals for both the fill rate and the plant’s operation that balance the needs of all parties. With Ethiopia aiming to begin power generation at the dam by the end of 2020, time is of the essence.

Difficult as it will be to resolve these immediate issues, the risk of future clashes could be severe if the parties do not also reach agreement on a longer-term basin-wide river management framework. Indeed, as populations grow and climate change renders annual rainfall more erratic, Ethiopia could seek to further exploit the Nile waters to expand its economy; for its part, Egypt – already worried that its volumetric share of the Nile waters is insufficient – could become even more alarmed about the national security implications of reduced water flow. While Cairo’s short-term focus is on the implications for water flow during reservoir filling in Ethiopia, in the medium term, Egypt worries acutely that Sudan could take advantage of better regulated flows of water from the GERD to substantially expand irrigation, a development that might be damaging for Egypt because Sudanese farming would consume significant amounts of water and thus reduce further Egypt’s volumetric share of the Nile waters.

External actors have long encouraged riparian countries to forge an updated transboundary agreement for sharing the Nile waters. One platform for such cooperation is the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI), a multilateral forum for all eleven riparian states – Egypt, Ethiopia, Sudan, Uganda, Kenya, Rwanda, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania, South Sudan and Eritrea, which has observer status. The NBI was established in 1999, with support from a number of bilateral and multilateral partners, notably the World Bank.

The platform has been weakened due to tensions among Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan. At its founding, member states agreed to pursue cooperation along two tracks. The NBI secretariat was to champion a technical track, outlining measures for sustainable development of the basin. The political leaders of all riparian countries, meanwhile, were to pursue a political-legal track, whose conclusions were to be spelled out in a Cooperative Framework Agreement that would outline mechanisms of cooperation between all parties. If the parties achieved consensus, the plan was to convert the NBI into a permanent commission to promote basin-wide cooperation.

Talks broke down after Addis Ababa rallied the upstream riparian states to endorse the Cooperative Framework Agreement without waiting for the backing of downstream partners. Ethiopia was particularly supportive of the framework’s call for “equitable utilisation” of the Nile waters, which satisfied its longstanding demand for upstream countries to benefit more from the river through development projects. Egypt and Sudan both objected, perceiving the text as rewriting the 1959 agreement that allocated 100 per cent of the Nile waters to the two countries furthest downstream.

Cairo and Khartoum pressed for the document to clearly stipulate the need to protect water security for all countries and demanded that member states be explicitly required to offer prior notification of all major development projects in the basin. They lost the argument. Upstream countries baulked at what they perceived as a demand by their downstream counterparts for an effective veto over projects. Egypt and Sudan suspended their participation in the NBI shortly afterward (Sudan subsequently rejoined). Addis Ababa’s announcement of the GERD the following year only added to those tensions.

Today, the EU and Germany are the NBI’s principal remaining external funders. The World Bank, having initially reduced its participation amid heightened tensions among parties, also eventually resumed support through the Cooperation in International Waters in Africa program. Though the initiative has been undermined, it still undertakes research and maps out scenarios for future options in terms of water use, besides focusing on the effects of climate change and other pressures, including population growth. The NBI cannot, however, be effective without the participation of Egypt, a key player on the basin. Considering the warmer relations between Addis Ababa and Cairo, it would make sense for Egypt to rejoin this initiative, which remains the best available forum for discussions on a basin-wide settlement.

The wider forum enjoys two principal advantages over the trilateral discussions. The talks among Cairo, Khartoum and Addis Ababa are project-specific and focused only on the GERD issue. The NBI, on the other hand, can craft a more forward-looking basin-wide consensus to govern resource use and avert conflict down the road. Also, the initiative would involve all the countries up and down the basin and could produce a consensus that goes beyond Ethiopian, Egyptian and Sudanese interests.

Beyond such questions, Egyptian, Sudanese and Ethiopian leaders need to tackle the political issue of how to sell any compromise – on both the GERD and long-term water sharing – at home. So far none has mustered the political courage to embrace deals that risk exposing them to domestic criticism.

III.High Anxiety in Egypt

The Nile Waters Dispute: The Egyptian Position

In this video, Crisis Group’s former North Africa Project Director Issandr El Amrani reflects upon Egypt’s position about the dam. CRISISGROUP

For Egyptian authorities, the first-order priority is to shield the country from potentially drastically reduced water flow when the GERD is completed. Egyptian media outlets close to the security forces, echoing the country’s leadership, regularly portray the dam as a major threat to Egypt. Likewise, assessing how the country was blindsided by Ethiopia’s plans to construct the GERD is a popular topic for discussions in online chats. In an otherwise subdued campaign, all candidates in Egypt’s March 2018 presidential election declared their intention to protect the country’s Nile interests. A new constitution adopted in 2014 requires the state to preserve Egypt’s “historical rights” to the Nile.

As the country most dependent on the Nile, and the dominant power in the region, Egypt was traditionally most active in river-related diplomacy.

As the country most dependent on the Nile, and the dominant power in the region, Egypt was traditionally most active in river-related diplomacy, particularly during Gamal Abdel Nasser’s time in office (1954-1970). During the decades of anti-colonial struggle after World War II, Nasser built close relations with counterparts across Africa, an investment that earned the country’s positions sympathy.

Under Nasser’s successors, however, Egyptian ties with the continent frayed. Of particular note, Anwar al-Sadat ran afoul of Ethiopia when he took Somalia’s side in the Ogaden War (1977-1978). It was the first of several moves leading Addis Ababa to accuse Cairo of backing its foes as part of a policy of encirclement. Hosni Mubarak, who assumed power after Sadat’s assassination in October 1981, showed no interest in recovering Egypt’s position on the continent. Cairo cut off relations with Ethiopia after the 1995 assassination attempt against Mubarak in Addis, claimed by Egyptian Islamist militants but which he accused Ethiopian authorities of abetting. Egypt later backed Eritrea’s war of secession. The resulting rancour coincided with the period of Ethiopian economic growth under Meles which, in turn, helped pave the way for the GERD. The 2011 announcement of the dam’s construction came at a time of tense Cairo-Addis relations when Egypt was largely disengaged from regional diplomacy and after it had frozen its participation in the NBI.

At the time, the country also was grappling with the turbulence that followed Mubarak’s ouster in February 2011. Otherwise preoccupied, Cairo was blindsided by Ethiopia’s proclamation about the dam and could muster only weak opposition. “Egypt did not have a state at that time”, said an Addis Ababa-based Egyptian diplomat, who argues that Meles took advantage of instability in Cairo to pursue a much larger dam than initially envisioned: “They doubled, tripled and then quadrupled the size of the reservoir”. Demanding that Ethiopia halt construction, Cairo struggled to put together a coherent policy response during the short-lived presidency of Mohamed Morsi. Though some Egyptian politicians called for military action, Morsi was in no position to back up such bluster.Egypt’s diplomatic disarray, meanwhile, came at the cost of Ethiopia making substantial progress on the GERD while disregarding the possible downstream impact.

Since coming to power in 2014, President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi has reinvigorated Egypt’s Nile waters diplomacy. The Egyptian security and diplomatic apparatus threw its weight behind efforts to secure a deal with Addis Ababa and Khartoum after Sisi took office. Repeated rounds of talks yielded the aforementioned March 2015 declaration of principles, in which Ethiopia acknowledged the need to shield downstream countries from “significant harm” from the GERD. Sisi has cautiously welcomed Abiy’s ascension to office and hopes to use warmer ties with Addis Ababa to secure an agreement on the GERD that clearly protects water flow downstream. In pursuing this deal, he is partly motivated by domestic political considerations: he has been intent on shoring up his authority and support for his controversial attempt to lift the Egyptian constitution’s two-term limit on the presidency at a time of waning popularity. The Nile issue gives him an opportunity to rally nationalist sentiment. Sisi now also has a prime regional perch from which to make Egypt’s case: in February 2019, he assumed the rotating AU chairmanship.

Sisi’s government has thrown considerable energy into the tripartite talks. Though Egyptian diplomats privately concede it is too late to stop the dam, they have sought to persuade their Ethiopian and Sudanese counterparts of the need to abide by the terms of the 23 March 2015 “declaration of principles” – notably its provision that all parties ensure that the GERD causes no significant harm to downstream countries.They are thus eager to strike a deal on the GERD’s operations that does not sharply reduce water flow downstream. They worry about precedent: Ethiopia is estimated to have hydropower capacity of up to 45,000 megawatts and it might unilaterally pursue other hydropower projects down the line. Cairo would vigorously object if Addis Ababa undertook major new projects. Egypt also needs an arrangement with Sudan, which, in the words of an European diplomat, “Cairo views as a long, dry sponge that could soak up all the water”.

As seen, a principal hurdle is the absence of mutually agreed-upon studies of the dam’s impact. According to an Egyptian diplomat, “There are no [good] empirical or mathematical models for the actual effect on water flows as a result of the dam, and no exact numbers for what will be affected and how, and for how long”. It is not for lack of trying. In 2015, the Nile basin countries agreed to commission two firms, one French and one Dutch, to study the GERD’s potential effects. But the Dutch firm, nominated by Cairo, walked away; Egyptian authorities complain that the Ethiopians did not fully cooperate. The French firm continued its work, producing an inception report, a preliminary document laying out the terms for further evaluation of the project, but the parties could not agree on a way forward. In December 2017, Egypt proposed that the World Bank step in to conduct an independent study, an offer Ethiopia rejected.

A third effort at reaching consensus came on 15 May 2018, when the water and foreign ministers of Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia met in Addis Ababa and agreed to form a panel of experts to conduct studies. Yet despite initial enthusiasm, little progress has been made insofar as the agreement allows each country to employ its own experts and provide its own non-binding reports.

Whoever is to blame for the paucity of information, it creates a real problem for all parties as they try to plan for the expected disruptions from reductions in water flow. A former senior Egyptian agriculture ministry official said:

[pullquote]We do not seek to sabotage the dam. But we need clear information on its impact. We need mathematical models to determine what percentage of water will be lost. That way, we can gauge the impact on lost farmland and water losses at home. We need to confirm the threat level to Egypt.[/pullquote]

That sentiment attracts sympathy outside the region. Western officials, for example, are generally critical of the Egyptian authorities’ handling of the dam crisis (particularly their early posture suggesting that they could stop the project unilaterally) and of the country’s water use practices. But they support the core Egyptian demand for transparent, comprehensive studies to understand the GERD’s full impact.

Until recently, Cairo’s poor relations with Addis Ababa and Khartoum were an obstacle to reaching any agreement on the dam. Several events exacerbated tensions: in 2016, Ethiopian authorities condemned Cairo’s decision to host Ethiopian Oromo rebels; in January 2018, Ethiopia accused Egypt of sending troops to Eritrea, reportedly as a show of force aimed at both Ethiopia and Sudan, claims that Eritrea disputed. Sudan, in turn, massed troops near the border with Eritrea.

Though Prime Minister Abiy’s more recent outreach to Egypt has eased bilateral tensions somewhat, the two countries’ authorities eye each other suspiciously. Egypt appears to have adopted a wait-and-see attitude toward Abiy and his administration, unsure of the new prime minister’s staying power and not fully trusting his assurances that Ethiopia will protect Egypt’s interests regarding Nile waters.

Egypt’s relations with other relevant countries are also evolving. Sisi embarked on concerted diplomatic efforts with the other seven Nile basin countries, not so much to win immediate support for Egypt’s positions on the GERD as to line up allies for later negotiations over basin-wide water management. He offered Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo diplomatic support, including during Cairo’s recent term on the UN Security Council, rejecting calls for sanctions targeting their leaders’ attempted extra-constitutional power grabs. He cultivated an especially close relationship with President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, traditionally a rival of Sudan and to a lesser degree Ethiopia. Several senior Egyptian intelligence and military officials have taken up diplomatic posts in the Nile basin capitals. Sisi also traded visits with his Kenyan counterpart Uhuru Kenyatta, seeking to counterbalance Nairobi’s defence pact and close relationship with Addis Ababa.

Cairo’s growing role vis-à-vis South Sudan is part of a broader attempt to reassert itself as a Horn power after years of absence under Sadat, Mubarak and Morsi.

Egyptian re-engagement has been particularly striking in South Sudan. Since at least 2015, Egyptian officials and security agencies have built close ties with their counterparts in Juba, inviting several South Sudanese delegations to Cairo. Egypt also lobbied on South Sudan’s behalf at the UN Security Council, prompting South Sudan’s President, Salva Kiir, and his allies to describe Egypt as a treasured ally. In March 2018, Egypt supported South Sudan’s request to join the Arab League. Cairo’s growing role vis-à-vis South Sudan is part of a broader attempt to reassert itself as a Horn power after years of absence under Sadat, Mubarak and Morsi.

Gaining external backing is one thing; preparing Egypt’s public for inevitable adjustments when the dam is completed is another. Though officials acknowledge the GERD is a reality, they have done little to sensitise Egyptians to this fact. Egypt’s media – policed by the military and security apparatus – continue to suggest that military action could stop the dam’s completion. Opinion pieces regularly appear in the Egyptian press and on social media boasting of the size of the nation’s military and its ability to project force upstream, while amplifying the national security threat posed by the GERD.

In reality, as many analysts warn, the dam will compel Egypt to accelerate long overdue reforms in water consumption, rolled out haltingly in recent years. The country uses about 85 per cent of its water for its thirsty crops, with the main method being highly inefficient open-field irrigation. Studies show that this surface irrigation method “causes high water losses, decline in land productivity and salinity problems”. And yet, to date, officials have not publicly laid out what the GERD would mean for Egypt’s water use patterns.

External actors could help Egypt undertake adjustments that will be needed in the early years of GERD implementation. The EU already has offered to explore guarantees (including loans) and use other instruments to support downstream countries in years in which drought or other shocks jeopardise food security. Local private-sector actors argue that with outside help, notably from the Netherlands – a world leader in sustainable agriculture and efficient water use – Egypt could put in place measures to mitigate harm from reduced water flow.

IV.Sudan: Angling for Benefits

Poorer and less populous than Egypt, Sudan historically has been a weaker player in the Nile basin. For decades prior to South Sudan’s 2011 independence, it was embroiled in its own civil wars. Still, it has long asserted what it considers to be its rights under the 1959 agreement. Like Egypt, Sudan froze its participation in the NBI in 2010, believing that upstream countries had disregarded the interests of downstream countries in endorsing the Cooperative Framework Agreement and, once Ethiopia announced the GERD in 2011, expressed opposition to the project it feared would limit water supply downstream.

Khartoum was doubly caught off guard by the GERD announcement, of which it had no advance notice. It came at a time of domestic unrest. Khartoum was also bracing itself for the shock of South Sudan’s impending independence in July. Its opposition to the GERD was thus relatively muted. In 2012, however, President Omar al-Bashir’s government shifted its stance on the dam entirely, having been persuaded by Sudanese water experts and Ethiopian leaders that the GERD would help Sudan. Signalling its acquiescence in Ethiopia’s plans, Khartoum rejoined the NBI that November.

Indeed, it appears that Sudan stands to significantly benefit from the dam. Its abundance of arable land and water gives the country enormous potential for the development of commercial agriculture. Once completed, the GERD could curtail the Nile’s flooding in Sudan and thus reduce sedimentation, saving the country millions of dollars it spends annually clearing silt from agricultural fields. By offering Sudan more regulated water flow throughout the year, the dam could allow for several harvests annually and greater crop yields. If the country adapts quickly when the GERD’s reservoir is filled, it could irrigate millions of acres of new farmland.

Sudan hopes to benefit from foreign interest in its agricultural potential, particularly from Gulf states and Turkey, to boost investment. Saudi Arabia, for example, sees Sudan as contributing to its long-term food security; Port Sudan is located less than 400km from Jeddah and would be a ready transfer point for Sudanese produce. Riyadh has a long track record of investment in Sudanese agriculture, and though the results have been disappointing, its interest is undiminished. Qatar, Turkey and the UAE likewise all wish to expand their investments in Sudan’s agriculture sector. Ankara is contemplating a joint farm scheme in Sudan. Already, Gulf monarchies are said to have bought thousands of acres of arable land for long-term use when Sudan’s business environment improves. Even Egypt has discussed plans to grow some of its staples (particularly wheat, of which it is the world’s largest importer) in Sudan. The two countries have formed a bilateral commission to push the proposal forward.

The GERD could yield other benefits for Sudan. Purchasing hydro-electricity from Ethiopia will likely be cheaper than producing it domestically. Better-controlled water flow likewise would enable it to boost its hydropower production.

As a result, Sudan has largely supported the GERD project in the course of the tripartite talks. It has downplayed concerns that the dam could sharply reduce water flow downstream and urged Cairo to accept that the dam could yield basin-wide benefits, including expanded agricultural production in Sudan and, potentially, hydropower exports to Egypt.Sudan’s primary demand of the Ethiopians, which accords with an Egyptian one, has been that Addis Ababa should accede to a transparent study of the project. Its main concern on this score is that any structural defects in the dam would be a disaster for Sudan; the dam is located near its border, and flood waters would submerge swathes of its territory if the structure were to collapse. Still, Sudan has played a constructive role in pushing the trilateral talks forward. Most significantly, its representatives have indicated to Egypt that even after the GERD is completed, they will not tap water for agriculture so aggressively as to threaten water supply downstream. Egypt does not fully trust those promises.

Khartoum’s pro-GERD stance has worsened its already strained relations with Egypt. At odds with Cairo for decades over Halayeb, a triangle of land on the Red Sea coast claimed by both countries, Khartoum over recent years has also incurred the Egyptian government’s wrath by sheltering members of the Muslim Brotherhood, which was outlawed under both Sadat and Mubarak and now, after its brief stint in power in 2012-2013, is again proscribed and the target of repression. Bashir’s about-face on the dam only further angered Cairo. More broadly, Egypt’s government has long viewed Sudan as a potential base for the spread of Islamism in the region, a development it perceives as a threat to its hold on power.

As outlined, Egypt’s primary concern is that Sudan might expand its water use to Cairo’s detriment. So far, though Khartoum is entitled to 18.5 million cubic metres annually under the 1959 Nile agreement, it taps only about 12 to 14 billion cubic metres a year because it is under-developed. Sudan is citing its current light consumption as justification for unilateral expansion of its Nile water use down the line, saying it would remain within treaty obligations. If the GERD enables Sudan to expand agricultural production, it would use more water, on top of Ethiopia’s own increased use. Such extra consumption would strain Egypt’s own supply. Bashir irritated Cairo further by offering to “donate” some of Sudan’s Nile treaty allotment to Ethiopia for the purpose of filling the dam’s reservoir. In turn, Sudanese officials accuse Egypt of arrogance and wilful blindness to the merits of Khartoum’s position. A Sudanese water expert said:

[pullquote]There are huge benefits [to Sudan] and trying to deny them is absurd. Egypt’s attempt has been to scare Sudan away by circulating stories that [the GERD] might collapse [and flood Sudan]. But Egyptian specialists actually admit that it is going to benefit Sudan, and this is why they are worried![/pullquote]

Khartoum’s relations with Addis Ababa historically have been warmer than with Cairo. Bashir’s government cultivated lasting ties with men who would become senior figures in Meles Zenawi’s government by supporting them when they were leading the armed insurrection against Ethiopia’s former Marxist regime in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Relations hit a rough patch at the turn of the millennium due to Meles’s support for South Sudanese independence, but endured nonetheless. Until Addis Ababa’s recent peace deal with Asmara, Sudan and Ethiopia shared a common enemy in the Eritrean government, which Khartoum long accused of supporting rebels in eastern Sudan. This dynamic helps explain why Khartoum took the risk of upsetting Cairo by backing the GERD.

The U.S. government’s continued designation of Sudan as a state sponsor of terrorism, along with the poor business environment, keeps foreign investors away.

The burning question is whether President Bashir will be in power long enough to enjoy the GERD’s putative bounty. Entering his third decade in office, he faces dissent inside and outside the ruling National Congress Party (NCP). Some in the NCP, particularly younger officials but also others with whom he has fallen out, blame the president for a major economic crisis characterised by spiralling costs of living. Bashir’s critics – within the NCP and outside it – also view him as a liability in terms of relations with the West. The U.S. government’s continued designation of Sudan as a state sponsor of terrorism, along with the poor business environment, keeps foreign investors away and blocks Sudan’s access to the international debt relief or bailouts necessary to salvage its economy. The International Criminal Court’s indictment of Bashir for atrocities committed in Darfur also makes it hard for Western donors to engage with Khartoum, though they maintain contact on efforts to curb migration to Europe and on counter-terrorism. Bashir’s fear of a palace coup explains his cabinet reshuffles, which interrupt efforts at reform.

Beyond that, popular discontent runs deep. In late December 2018, the government’s decision to raise the price of bread sparked demonstrations in cities throughout the country, with chants escalating rapidly from complaints about prices to calls for Bashir’s downfall during marches on the presidential palace. On 22 February, Bashir declared a state of emergency for a year, sacked the national and provincial governments, and replaced all regional state governors with security officials. The move, seen as a desperate gambit to survive the protest movement, did little to stop the demonstrations.

The protest movement against Bashir has brought a further twist in relations between Cairo and Khartoum. Despite Egyptian authorities’ irritation with Bashir’s positions on various issues, including the GERD, they have lent him unwavering support as he battles to save his political life in the face of the most sustained protest campaign Sudan has seen in decades. Bashir travelled to Cairo in the second week of January and received Sisi’s unequivocal backing. The embattled Sudanese president requested Egyptian support in lobbying for financial assistance from the Gulf monarchies to stabilise Sudan’s economy. If Bashir survives, it is possible his stance on the GERD may shift yet again to align more closely with Cairo than with Addis. Ethiopia has issued no public statement on the uprising in Sudan. Abiy abruptly cancelled a planned 4 March visit to Khartoum, but neither his office nor the Sudanese president’s offered an explanation.

Another important question, whether Bashir survives or not, is how Sudan will pay for the infrastructure upgrades and other improvements it needs to reap the GERD’s promised benefits. Finding donors or investors will not be easy. The private investment climate in Sudan is poor and many foreigners who have expressed a theoretical interest are waiting. Bashir has long privileged the security sector and paid little heed to economic needs. The military’s control of economic management underpins the country’s chronic foreign exchange shortages, which contribute to the inflation and other economic problems that have helped bring protesters into the streets. It also alienates investors, who complain of byzantine regulations enforced by an inflexible bureaucracy. Sanctions and Bashir’s troubled relations with Western powers and international financial institutions make matters worse. For many foreign investors, the key issue is how long Bashir stays in power and how his eventual succession will be managed.

The GERD’s economic boons for Sudan are only likely to show up sometime in the future. The year-long state of emergency, repression of protesters and uncertainty over when – or if – Bashir will fall makes it even more unlikely that substantial foreign investment will flow into Sudan anytime soon.

V.Reaching Agreement on the Nile Waters

Though mutual suspicion among Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan has stymied diplomatic efforts to resolve the dispute, in principle all sides stand to gain from greater cooperation in sharing the Nile’s water.

Ethiopia needs external consumers for the hydroelectric power it will generate and thus needs good relations with its neighbours, particularly Sudan, a potential top export market. Given foreign currency shortages at home, it could also benefit from outside funding to complete the GERD and knows it would face diplomatic blowback if it dramatically slowed the water flow to Egypt. Sudan stands to gain enormously from the dam, provided it can attract the necessary investment in its agricultural sector. It also has an interest in ensuring that the dam’s construction is solid: any breach of water would inundate its crops and low-lying towns and villages. As for Egypt, the downstream country most dependent on Nile waters, it sorely needs the upstream countries’ cooperation. In return, Egypt could offer access to markets in its more advanced economy and also joint investment, including in agricultural ventures, with Sudan and Ethiopia.

Beyond reducing risks of confrontation, there are many arguments for a compact to ensure better management of Nile waters. Water stress will weigh ever more heavily upon Nile basin countries in the years ahead.Recurring drought has already made rain-fed agriculture, upon which millions depend, increasingly difficult to sustain without modifications to antiquated agricultural practices. Climate change will likely contribute to more erratic water supply and stream flows. Population growth up and down the basin also underlines the need for more sustainable water use. In 1960, the total population of Egypt, Ethiopia (including Eritrea) and Sudan (including South Sudan) was 113 million. This number rose to 487 million in 2016. The UN estimates that, together, these countries will add another 200 million people before 2050. Per capita water use will also rise, amid greater urbanisation and industrialisation in each country.

An expert assessment of the GERD’s design by a Massachusetts Institute of Technology working group, using the limited data available, has identified three flashpoints if Nile basin countries cannot agree on cooperative water management. First, the GERD will create an unparalleled resource management problem-in-waiting. Egypt’s Aswan Dam, completed in 1970, can store up to 169 billion cubic metres of water in its reservoir. The GERD’s reservoir can hold 74 billion cubic metres. Thus, there will be two major storage reservoirs in the same international river basin, each with a huge capacity compared to annual river flow, but with no institutional or legal arrangement for managing both together. The danger is that both countries could seek to simultaneously fill up their reservoirs in anticipation of drought, for example, fostering conflict because there would be insufficient water to fill up both dams. Without a cooperative management framework, and particularly if Egypt feels that its water supply is threatened, chances for conflict would be high.

Secondly, any sudden major reduction of water flow could trigger an ecological disaster. At present, excess water in the Nile flushes salts out of Egypt’s agricultural land into the Mediterranean. Diminished water supplies could lead to rapid salinisation and dramatic declines in agricultural productivity, throwing millions of farmers out of work, driving up food prices and provoking a political crisis. Technical solutions exist, but to implement them the parties will need clarity about the GERD’s effect on water flow and the timetable for filling its reservoirs.

Thirdly, Ethiopia and Egypt could disagree about how to manage water flow during years of light rainfall. In those periods, Ethiopia will still want to store water for power generation while Egypt and Sudan will want extra water for agricultural and municipal use.

None of these potential problems presents an insurmountable engineering challenge, though the three countries would need to set aside their mutual distrust. They also need to surmount complications related to the secrecy with which public policy is crafted in all three countries. Addis in particular conceals its Nile waters deliberations, partly because it worries about Egyptian sabotage in part due to statements by Egyptian authorities threatening to take military action to stop the dam. Ethiopian authorities reported that they foiled an attempt by Ethiopian rebels operating out of Eritrea to attack the GERD site in March 2017. Addis Ababa has allegedly hidden details of other dams from the downstream countries in the past.

Any mediation role for Gulf powers or for Turkey would be greatly complicated by their rivalries and battle for influence.

Multiple actors maintain open lines with the riparian countries and could nudge them toward compromise. China has close ties with both Egypt and Ethiopia. U.S. diplomats have discreetly shuttled between Addis Ababa and Cairo to explore possibilities for resolution, though some Ethiopian officials see the Americans as overly sympathetic to Egypt. The EU’s special representative for the Horn of Africa has engaged authorities in Cairo, Khartoum and Addis to encourage greater cooperation. Germany’s special envoy for Nile affairs has also met government representatives in the three capitals.

The Gulf powers and Turkey might also play a role. Both sides in the current Gulf crisis (Saudi Arabia and the UAE on the one hand, Qatar on the other) wield influence along the Nile. Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, seeing the region primarily through a security lens, have upped spending in the region over the past few years, largely to curtail Iran’s influence. Sudan has been among the chief beneficiaries, receiving aid and investment in return for severing ties with Tehran and sending thousands of Sudanese to fight with the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen. Riyadh and Abu Dhabi may not fully trust President Bashir and have not provided the level of support he craves, but they maintain close ties. In Egypt, those two powers are deeply invested in President Sisi’s success, seeing him as a bulwark against the Muslim Brotherhood. Both have given him significant aid and plan to expand economic ties. The UAE also intends to support major infrastructure projects in Ethiopia. Abu Dhabi has privately signalled that it would be willing to mediate between Cairo and Addis. It has already helped Abiy make peace with Eritrea.

For their part, Qatar and Turkey enjoy especially close ties to Sudan and warm relations with Ethiopia. Turkey is rehabilitating the Ottoman-era Suakin port (recent reports that it intends to establish a naval base there have alarmed Cairo). Qatar was among the first foreign governments to come to President Bashir’s defence as the popular unrest swelled, though how committed Doha is to his survival is an open question. Qatar has also offered Ethiopia financial aid and Turkish companies are among the largest investors in that country. Both Doha and Ankara are seeking to expand their economic footprint in the Horn and Nile basin while building diplomatic clout.

That said, any mediation role for Gulf powers or for Turkey would be greatly complicated by their rivalries and battle for influence. Though Egypt sided immediately with the Saudi bloc in its spat with Qatar, neither Sudan nor Ethiopia officially picked sides; both could still come under pressure to choose. Ethiopia in particular has become a site of Gulf-related competition. Before Abiy took office, Addis Ababa was officially non-aligned in the Gulf dispute. Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, however, perceived it as being close to Qatar (which offered Addis substantial budgetary support) and Turkey (whose investors have staked millions of dollars in construction and other sectors). Abiy is seen as having pivoted toward the Saudi bloc. Qatar and Turkey reportedly remain keen to reposition themselves as key players in Ethiopia. Cairo, in accord with Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, looks askance at Ankara and Doha’s efforts to cultivate allies in the region, particularly in Sudan, where they have invested substantially of late. These contrasting goals mean that it will be hard for the Gulf states and Turkey to serve as arbitrators along the Nile.

A.Policy Options

Despite mutual suspicion, a window of opportunity currently exists to find a way forward. Ethiopia’s transition has led to improved ties between Addis and Cairo, while Khartoum stands to be one of the GERD’s chief beneficiaries. External actors should support efforts to strike a deal before the dam is completed by encouraging all parties to show greater flexibility. All sides abandoned their maximalist positions in March 2015, when they effectively opened the door to a negotiated solution. By agreeing to discuss implementation of the dam, Egypt implicitly accepted Ethiopia’s demand for more equitable use of water resources. Conversely, by committing to avoid significant harm to downstream countries, Ethiopia accepted Cairo’s concerns about mitigating downstream impact. In talks, authorities in Sudan also signalled to Cairo that they do not intend to expand water use in a way that would threaten supply to Egypt. What is now required is for the three countries’ leaders to take confidence-building measures, paving the way for a deal well in advance of the GERD’s completion.

The most effective approach likely would proceed in phases:

a) Advancing talks on the GERD’s impact

To unblock the tripartite talks, Ethiopia should cooperate more fully with Egypt’s request for the parties to obtain binding technical advice from respected consultants outlining a fill rate timeline that neither unduly delays the project nor ignores downstream countries’ concerns about water flow. Past efforts in this vein ran aground due to suspicion among the parties. Particularly contentious has been the question of whether the studies’ findings would be binding. Egypt favours this position while Ethiopia fears it could be used to excessively constrain them.

Addis Ababa should accept that Cairo’s demands for such a study accord with international water law, which recommends that upstream countries assert their right to develop their resources while avoiding significant harm to downstream partners. Ethiopia should avoid stalling the initiatives under way since 2013 that aim to resolve this matter. As a further incentive for Addis, the EU’s long-term lending institution, the European Investment Bank, which Ethiopians perceive as less pro-Egyptian than the World Bank, could agree to fund the final stages of dam construction. To reassure Sudan, such a study would also address the dam’s safety.

To further build confidence, Prime Minister Abiy could invite his Egyptian and Sudanese counterparts on a joint tour of the dam site to lift the veil of secrecy that surrounds the project and demonstrate willingness to pursue a negotiated solution. These steps would have ancillary benefit: they could provide both Abiy and Sisi the domestic space required to sell a compromise to their constituencies at home. In the same spirit, Ethiopian and Egyptian security services could resume full cooperation and information-sharing. Egypt’s leaders repeatedly complained in the past that they had to negotiate with Ethiopian politicians over Nile water issues while the security establishment made all the decisions. Ethiopia under Abiy may be more open to meaningful engagement.

Outside actors could help: as seen, the European Investment Bank could play a part; the UN could offer technical support; the U.S., Saudi Arabia and the EU could encourage authorities in both Addis and Cairo to compromise.

Achieving a breakthrough on the issue of the timeline for filling the dam would significantly reduce tensions and pave the way for more substantive talks on basin-wide cooperation.

b) Negotiating a longer-term Nile treaty

In a second phase, the parties should support efforts toward a long-term trans-boundary cooperation agreement up and down the basin. Egypt could signal good faith by rejoining the NBI, the most effective platform to reach a broader Nile basin agreement. This gesture would be both forward-leaning and justified by the present state of affairs: Egypt (along with Sudan) froze participation in the NBI because upstream countries refused to abide by the 1959 Nile agreement, which allocated 100 per cent of Nile waters to the two downstream countries. Those disagreements are now moot as explained above: the dispute is no longer a battle for hydro-hegemony but rather an argument about how to share resources in a way that benefits all riparian states.

In 2017, Egypt signalled its intent to re-engage with the NBI by sending lower-level officials to meetings. Its return to full participation could give a fillip to efforts to craft a permanent institutional framework for basin-wide cooperation. NBI member states, in turn, could invite Eritrea, a close Egyptian ally, to upgrade its status to full membership. That step, together with Egypt’s improved ties with Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan and Uganda, ought to provide Egypt with greater confidence that its concerns will receive a more favourable hearing in future talks. (In the past, the Egyptians perceived Ethiopia as the dominant player within the NBI.)

Any Nile basin agreement would need to respect the interests of all eleven basin countries.

Any Nile basin agreement would need to respect the interests of all eleven basin countries – which, apart from Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan, include the upstream countries of Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda. And it would need to lay out a framework for cooperation and consensus-building regarding GERD developments to avert similar showdowns in future. The prospect of such a framework that would protect Egypt’s water supply for years should appeal to President Sisi. He could publicly present it as a win insofar as it would provide guarantees that no longer exist in light of Ethiopia’s and other upstream countries’ rejection of the 1959 treaty. It also could create space for Sisi to more effectively implement long overdue reforms to increase water conservation and efficiency in Egypt.

At any rate, climate change-induced variations in water supply mean that the parties will have little choice in the long run but to make adjustments to their overall water management approach. Scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology project that the Nile basin will experience greater variability in rainfall patterns in the future – with more years featuring droughts or extreme floods – pointing to the need for greater cooperation between all riparian countries to avoid environmental shocks up and down the basin. If Egypt fully rejoins, the NBI could evolve into a permanent commission, as envisioned at its founding, offering a platform for sharing information between parties and providing strategic analysis to help the parties manage what will be a more difficult environmental terrain in the future.

c) Implementing reforms to improve water use

Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan all can do more to prepare for less water due to climate change. Egypt and Ethiopia, in particular, in the past have resisted calls to conserve water because public opinion in both countries viewed such steps as displays of weakness in the face of regional rivals’ demands. As the sides adopt a more cooperative posture, they should prepare to make necessary adjustments.

Adjustment should involve greater basin-wide cooperation that takes advantage of each country’s strengths. Ethiopia is ideally positioned as a hydropower generator: its high altitude, ample annual rainfall and relatively low average temperatures mean that it loses less water stored in dams to evaporation. Ethiopia could therefore serve as a hydropower production hub and export cheap power to neighbours.

Abiy’s government also should temper domestic expectations. The GERD undoubtedly will boost Ethiopia’s economy, but is unlikely to be the game changer government propaganda proclaims. Ethiopia’s economy remains weak and requires long-term reform. Four in five Ethiopians live in rural areas. Eighty-five per cent depend on subsistence agriculture. Average power consumption per connected household is ten times lower than the sub-Saharan African average. Private-sector participation in the country is low. Ethiopia is a difficult place to do business, with a slow, rigid and conservative bureaucracy. It is ranked 161 out of 190 on the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business index. Opening even a small business requires reams of paperwork and other bureaucratic hurdles. The GERD is only one step of many required to improve Ethiopia’s economic fortunes.

For its part, Sudan badly needs to reform to improve the country’s investment climate and attract funds to develop its vast tracts of arable land for agricultural use. Greater cooperation with neighbours, including Egypt, could pave the way for joint farms that would grow staples such as wheat and rice, earning Sudan foreign exchange while securing Egypt’s food supply.

With its larger economy and greater pool of technical expertise, Egypt has much to offer the other riparian countries, not least one of the continent’s most extensive markets. At the same time, it faces the most substantial water deficit among basin countries and therefore will require thorough reforms to its water management system. It should embrace more efficient means of irrigation across the board, prepare its farmers for the inevitable adjustments and sensitise its population to the need for less wasteful water use practices.

VI.Conclusion

The case for cooperation among Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan in resolving the Nile water dispute is unambiguous. All stand to benefit. Dangers of failing to work together are just as stark. The parties could blunder into conflict, with severe humanitarian consequences, if they cannot formulate technical fixes to allow the GERD’s construction to take place in a way that spares downstream countries economic and environmental shocks. And all could pay a steep economic and ecological price if they do not join forces and adopt a more forward-looking approach. Leaders of the three countries should seek agreement today, rather than wait until the project nears completion.