New leader has freed political prisoners and plans economic opening. But will liberalisation spin out of control?

It is the compound from which Emperor Menelik II conquered swaths of territory, where Haile Selassie passed judgment until he was toppled by a Marxist revolt in 1974, and from which Meles Zenawi, strongman prime minister until his death in 2012, plotted an Asian-style economic miracle on the Nile.

Surveying the same 40-hectare plot in the centre of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital, Abiy Ahmed, the most talked-about leader in Africa, sets out his grand plans for transforming Ethiopia. In an act of political theatre, he leads the FT on a tour of the prime ministerial grounds, from Menelik’s cathedral-sized banqueting hall to the cages where the emperor kept lions and the dungeon where he had disloyal generals and ministers tortured on the rack.

In Mr Abiy’s first one-on-one interview with the international media since he was catapulted to the premiership last April, he alternates between homespun prophet, hard man and visionary leader. He mixes humour with a tactile arm-grab worthy of LBJ. His sentences, delivered in proficient English, are laced with biblical references, Big Data and Michael Jackson. Committed to opening up Ethiopia’s closed political system, he is fascinated by the nature of popularity.

“If you change this,” says Mr Abiy, gesturing to the rubble-strewn compound and the rapidly changing skyline in the capital beyond, “you can change Addis. And if you can change Addis, definitely you can change Ethiopia.”

Improving his own surroundings, he says, is a metaphor for the transformation of a country that has, for 15 years, been the best-performing economy in Africa, but whose authoritarian government provoked a sustained popular uprising.

On his first day, he says, he ordered an overhaul of his office. In two months, what had been a dark and austere interior became a blindingly white luxury-hotel-style affair, replete with wall-to-wall videoconferencing screens, modern art and sleek white rooms for cabinet meetings and visiting delegations.

Cluttered storage rooms are now pulsing data banks and the ground floor is a California-style café — white, of course — where the premier’s mostly western-educated young staffers can sit and brainstorm. “I want to make this office futuristic. Many Ethiopians see yesterday. I see tomorrow,” he says. “This place has gone from hell to paradise.”

The youngest leader in Africa at 42, Mr Abiy is building a digital museum to celebrate Ethiopia’s history, a mini-Ethiopian theme park and a zoo with 250 animals. He envisages thousands of paying visitors coming each day.

“This is a prototype of the new Ethiopia,” says the former army intelligence officer and software engineer. “I have done so many great things compared to many leaders. But I didn’t do 1 per cent of what I am dreaming.”

His words may sound boastful, not to say arrogant, the sorts of qualities that have led many a leader in the past to cultivate a cult of personality. The recent precariousness of the country should also give pause for thought: only a year ago, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, the four-party coalition Mr Abiy leads, faced an almost existential crisis and there was even talk of a civil war.

Yet Mr Abiy’s first 10 months in office have been remarkable by the yardstick of any leader around the world.

In that time, he has overseen the swiftest political liberalisation in Ethiopia’s more than 2,000-year history. He has made peace with Eritrea; freed 60,000 political prisoners, including every journalist previously detained; unbanned opposition groups once deemed terrorist organisations; and appointed women to fully half his cabinet. He has pledged free elections in 2020 and made a prominent opposition activist head of the electoral commission. In a country where government spies were ubiquitous, people feel free to express opinions that a year ago would have had them clapped in jail.

“He says the most unbelievable things and then he ends up doing them,” says Blen Sahilu, a lawyer and women’s rights activist, referring partly to the unexpected peace treaty with Eritrea that brought an end to more than 20 years of military stand-off.

“In many ways, Abiy has been a shock to the system,” she says. “I’m still waiting to see whether the country can sustain that much change in such a short period of time and if these actions have a thoughtful follow-up strategy.”

Mr Abiy’s emergence has unleashed opportunity and danger in equal measure. Some fear that rapid liberalisation could spin out of control, leading to anarchy or violent ethnic separatism.

“It was a given that the euphoria was not going to last,” says Tsedale Lemma, editor in chief of Addis Standard, a website she edits from Germany. “Everyone is waking up to the grim reality that the previous EPRDF administration has left behind,” she says, referring to the four-party coalition that has ruled with a vice-like grip since 1991.

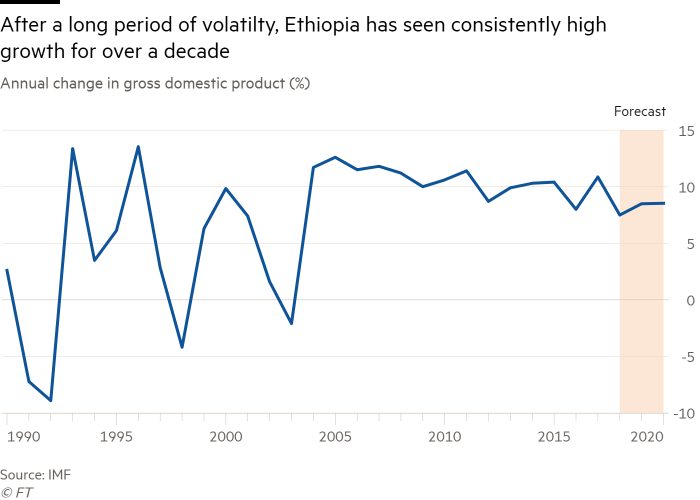

The EPRDF’s track-record was not all bad. For nearly 15 years, the economy had been growing at more than 10 per cent annually, according to official statistics. Even if overstated, growth has propelled a nation long associated with famine from an $8bn minnow at the turn of the century to an $80bn economy that has surpassed Kenya as the biggest in east Africa.

Driven by former prime minister Meles’s vision of a South Korean or Chinese-style “developmental state”, the government poured money into roads, giant dams, agriculture, health and education. Life expectancy has risen from 40 when the EPRDF took over by force in 1991 to 65.

Ethiopia came to be seen by international agencies as a model of authoritarian development and Africa’s best hope of emulating the sort of economic and social transformation engineered in Asia. But development came at a cost. In a country with more than 80 ethnic groups, resentment built up against the Tigrayans, who comprise only 6 per cent of the 105m population but who were seen as dominating power. That resentment was particularly strong among the Oromo, who make up roughly a third of the population, but who have long felt marginalised.

The crisis intensified after 2015 when the EPRDF rigged an election so completely it ended up with every parliamentary seat. Oromia, which surrounds Addis Ababa, erupted in violent protests, some of which targeted the foreign investments and industrial parks at the heart of the administration’s modernisation push.

In an unusual coalition, the Oromo were joined by the Amhara, who make up about a quarter of Ethiopians, and who had been used to running the country until the Tigrayans muscled in. The EPRDF responded with repression, imposing states of emergency, throwing tens of thousands of people into prison and shooting hundreds, perhaps thousands, of protesters.

Last February, amid talk of civil war, Hailemariam Desalegn, the ineffectual prime minister who had succeeded Meles in 2012, resigned, paving the way for a succession struggle within the EPRDF. Mr Abiy, who was then deputy president of the Oromia region, emerged the winner after two days of heated debate. Over the objections of the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front, one of the parties in the coalition, he was elected EPRDF chairman and hence prime minister, the first from Oromia in the nation’s history.

“I knew when they kept insulting me that I had won,” he says. “I ignored it and wrote my acceptance speech.”

Growing up poor, with a Muslim Oromo father and a Christian Amhara mother, in retrospect Mr Abiy seemed destined for the job. He even speaks Tigrinya after spending time as a young soldier in Tigray province. Indeed, he claims he knew from the age of seven that he would one day lead the country.

Stefan Dercon, professor of economic policy at Oxford university’s Blavatnik School of Government, says Mr Abiy’s historic task is to complete the economic transformation that Meles began. If South Korea’s miracle took 25 years, he says, “Ethiopia has completed half a miracle”.

Mr Abiy must now oversee the political and economic liberalisation needed, he says, to keep rapid levels of growth going for a decade or more, which would bring the country comfortably into middle-income status.

“Meles was too controlling, like Mao,” says Mr Dercon, who knew the feared but respectedEthiopian leader. “But command and control only works so far. That makes Abiy like Deng Xiaoping,” he says, referring to the Chinese leader whose opening and reform from 1979 propelled China’s economic lift-off.

While Mr Abiy remains wildly popular, particularly in the capital, not everything has gone his way.

He has faced one assassination attempt. And on October 11, a cadre of junior officers forced their way into the compound demanding to be heard. “I showed them I was a soldier,” he recalls. “I told them, if something wrong happens, you can’t kill me before I kill five or six of you.” He followed up with a macho burst of press-ups. Inside an hour, the incipient coup was over.

Such bravado aside, Mr Abiy must grapple with two challenges that would test even the most gifted of leaders.

The first is political. With censorship lifted and formerly outlawed groups unbanned, some people are demanding greater autonomy for their ethnically constituted regions. Armed militia are forming and youth gangs are carrying out vigilante attacks. Some 1.2m people were displaced in the first half of last year, although Mr Abiy says many of them have since returned home.

The prime minister hints he would like to tinker with the 1994 constitution, which some see as exacerbating ethnic rivalries but others regard as enshrining their rights. Such delicate changes, he adds, cannot be contemplated until he receives a hoped-for popular mandate in elections scheduled for next year. Some think the timing will slip.

He would also like to move to a presidential system in which leaders are directly elected, he says, rather than the current indirect process conducted through an EPRDF-dominated parliament.

While the prime minister preaches “unity of the nation and national pride”, the notion of a greater Ethiopia grates with those pressing for more regional autonomy. He has also moved against generals and officials from the TPLF in what many in Tigray province interpret as an assault, not on the corruption of party cadres, but on Tigrayans themselves.

“Every region has its own reason to fight for the continuation of the current federal system,” says Ms Lemma of the Addis Standard. “This is very dangerous. Abiy is stuck between a rock and a hard place,” she adds, referring to his need to unite the country and to satisfy demands for regional autonomy.

The prime minister professes to be unfazed by the forces he has unleashed. “Yesterday they were on the streets of Mekelle insulting me,” he says, referring to the Tigrayan capital. “But I love that. That is democracy.”

Mr Abiy says he wants to secure peace by persuasion, not through military pacification. “Negative peace is possible as long as you have a strong army. We are heading to positive peace,” he says.

Ultimately, Mr Abiy says, tensions will dissolve if the economy keeps expanding. “When you grow, you don’t have time for these communal issues.”

Keeping growth on track, he says, depends on dealing with past constraints, including debt and a seemingly perpetual foreign exchange crisis that puts import cover at barely two months.

He also wants to tweak the Meles developmental model, where so much money was funnelled into public investment that the private sector got crowded out. “Economically, we’re making big, big change, but the backlog is killing us. Today the debt is up to here,” he says, gesturing to his neck.

He has, he says, eased that situation by renegotiating commercial debt to concessional terms with China and others and by tapping states in the Gulf and the Middle East for loans and investment.

Growth slowed to 7 per cent last year, though Mr Abiy suggests this owes more to a realistic assessment than to an actual slowdown. Among his most critical challenges will be to decide how quickly to liberalise an economy that has produced impressive results, but also shown signs of running out of steam.

Recommended

Describing himself as “capitalist”, he nevertheless cites Meles as saying it is the government’s job to correct market failures. “The economy will grow naturally, but you have to lead it in a guided manner.”

Still, unlike Meles, Mr Abiy is less wedded to the idea that the state must control the economy’s commanding heights. He is moving swiftly towards privatisation of the telecoms sector in an exercise that should raise billions of dollars, as well as modernising a network that has fallen badly behind African peers.

Here too there are risks. “I need to realise the privatisation with zero corruption,” he says, adding that people who have stashed money abroad want to launder it back into the country.

Successful privatisation of telecoms could potentially lead to a similar exercise in energy and shipping, as well as sugar refineries and, most controversially, the successful national airline that has turned Addis Ababa into a continental hub. Mr Abiy says that, for the moment at least, he draws the line at banking.

“The biggest challenge for Abiy is not politics. It is jobs, jobs, jobs,” says Zemedeneh Negatu, an Ethiopian banker. With 800,000 students in university or college and 2.5m Ethiopians being born each year, lack of opportunity could quickly catalyse unrest, he adds.

As Mr Abiy steers through the political and economic rocks, one concern is that he could join a long line of once promising African leaders who turned authoritarian.

“Most of the dictators, including Mugabe [in Zimbabwe] and [Libya’s] Gaddafi, came as liberators,” says Befequadu Hailu, a blogger and activist, who was regularly jailed and beaten under the previous administration. “They ended up consolidating power in their own hands.”

Mr Abiy brushes aside such concerns, saying he will happily leave power if the people reject him. “I am sure I can’t be here eternally. I don’t know when, but I want to leave this office.”

Still, another voice tells him that he has a once-in-a generation opportunity to etch his name in Ethiopian history. “I will be popular if I lift 60m-70m people out of poverty,” he says. “If I do that, whether I like it or not, you will magnify my name.”

David Pilling and Lionel Barber in Addis Ababa