Safia Mohamed was amazed to discover that one of the last men hanged in Wales was a Somali like her. Most British Somalis arrived after 1990 and Safia never imagined they had been around for more than 100 years. The story of Mahmood Mattan, as she dug into it, also told a bigger story about Somali sailors in the UK and the racial prejudice they faced.

It all started with a conversation over dinner. I don’t know how we got on to the subject, but as we were leaving the restaurant my friend mentioned Mahmood Mattan, who was hanged for murder in 1952, and – I stared at her with wide eyes as she said it – later exonerated…

I was shocked and intrigued. We spent the rest of the evening on Google, trying to find out everything there was to know. And the more I read about Mattan, the more I found about the long history of my people in the UK.

When I was growing up, among Somali families who arrived here in the 1990s and early 2000s, no-one ever mentioned that Somalis had been in the country for more than a century. I had no idea.

Butetown is also known as Tiger Bay or The Docks. It has been a multicultural area for a long time, thanks to the seamen who arrived to work there from different parts of the British Empire – including British Somaliland.

The first Somali to arrive in Cardiff is recorded in the 19th Century, after the opening of the Suez Canal. But there were relatively few until 1914, when the start of World War One increased demand for their services.

The men worked on steam-powered ships in the merchant navy, often shovelling coal in the heat and dirt of the engine room. But they were able to save money to send home, and they saw the world.

As nomadic people, they didn’t have a problem spending their life on the move. “A man who has not travelled does not have eyes,” says one well-known Somali proverb.

My grandmother – my ayeeyo in Somali – told me about the 19th Century colonial division of Somalia a long time ago. Britain took the northern coastal area, creating “British Somaliland”.

France took the area now known as Djibouti. And lastly, Italy – “the worst people to be colonised by”, as my ayeeyo put it – took the south. But a few years before the British established control of their bit, Warsame’s father was taken from there by Germans.

“My dad was taken from Zeila by Germany in 1884. They put a lot of people on boats. They took a lot of people in the areas from Berbera to Djibouti and took them to Berlin,” he told me.

“Oh, as slaves?” I asked.

“No, they were taken there to be shown off and then sent back. The European colonies wanted to show their power and what they had. My dad was being sent to be a part of a human zoo. A place where German people could come and watch people from the parts of Africa Germany had controlled.

“The German public would pay and watch these people like they were animals. After a while, they would send people back, but my father had nothing to go back to so he escaped and jumped on to a boat, which was the start of his work as a merchant seaman.”

When people in the UK asked where he came from, he replied “Berlin”, which became his nickname.

More than a century later, it remains his son’s nickname too. Warsame was conceived in Somalia when his father was already quite old and didn’t reach Cardiff himself until 1969. He was one of the last to come to the UK to work as a seaman, he says.

During the war years, 1914-1918, Warsame’s father and his fellow Somali seamen prospered, as did others from Yemen and other parts of the empire.

However, at the end of the war, large numbers of white British sailors returned – and they needed work. The tensions resulted in the UK’s first race riots in Cardiff and Liverpool, in 1919.

The jobless ex-servicemen attacked black boarding houses and black people, says Nadifa Mohamed, a British Somali writer who is working on a book about Mahmood Mattan, “while the Somalis, among others, fought back and defended their areas”. It seems some were evacuated after the riots, but others stayed and stuck to their previous way of life even though there was less work.

“Living in Cardiff, the seamen were confined to boarding houses owned by the shipping companies and lived under a system of segregation that limited the jobs they could find, the places they could live and go,” Mohamed says.

“Despite the hardships though, they made a life for themselves in the multicultural docklands, where people from all over the world settled. They had cafes, mosques, Islamic schools, and support networks.”

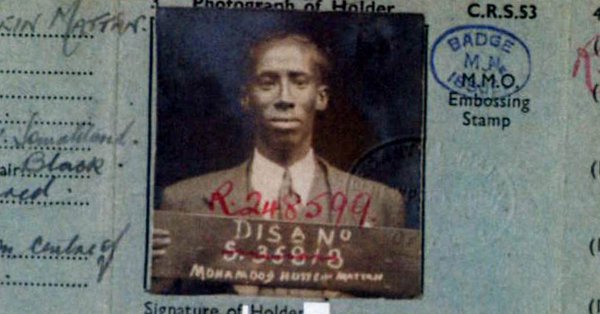

Mahmood Mattan turned up in Butetown sometime in the 1940s. He’d been born in British Somaliland in 1922 and, following the example of others from his community, he got a job on a ship.

In 1945 he met Laura Williams, a 17-year-old from the Rhondda Valley who was working in a paper factory, and three months later they married.

Prejudice against interracial couples was intense. “Even walking along the street led to insults and violent assaults from men and women,” says Nadifa Mohamed.

Together the couple had three sons, but it was hard to find a place where they were allowed to live together. At the time of Lily Volpert’s murder, they were living separately, in different houses on the same street.

Lily Volpert was a woman in her early 40s who owned an outfitter’s shop that doubled unofficially as a pawnbroker’s, on Bute Street, not far from the docks. On the evening of 6 March 1952 she was found dead there in a pool of blood, her throat cut by a razor. The sum of £100 – equivalent to about £3,000 today – had been stolen.

The police questioned many people, including Mattan. He told them he had not been on Bute Street that day. He had been at the cinema until 7:30pm and then set off for home, he said. But no-one could give independent confirmation of his whereabouts at 8.15pm, when the murder took place.

A Jamaican, Harold Cover, gave police a statement the following morning, describing a man he said he had seen leaving the Volpert shop – a Somali with a gold tooth and no hat or overcoat.

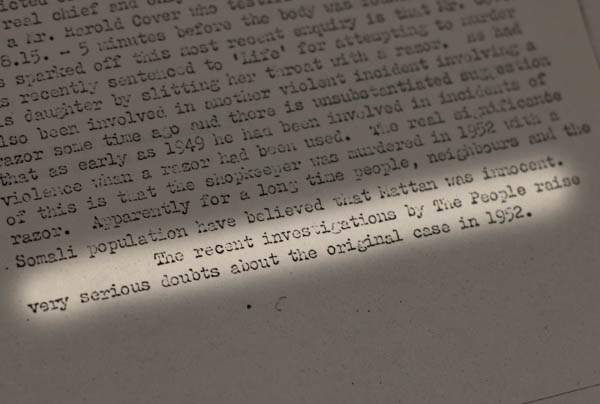

But Mattan had no gold teeth, and others who saw him that evening, before and after the murder, said he was wearing a hat and coat. Also, it’s now known that at the time Cover made this statement he identified the man he saw as another Somali, Taher Gass.

Police never disclosed to the defence the existence of the first statement. Nor did they reveal that four other people near the shop on the night of the murder failed to pick out Mattan at an identification parade – and that another, a 12-year-old girl, insisted he was not the man that she saw.

Unbelievably, in his closing speech Mattan’s own defence counsel, T E Rhys-Roberts, described his client as “this half-child of nature, a semi-civilised savage”.

Mattan was found guilty and sentenced to death. He was refused leave to appeal and hanged in Cardiff Prison on 3 September 1952.

Harold Cover was later jailed for life for attempting to murder his daughter by slashing her throat with a razor, while Taher Gass was tried for the murder of a man by stabbing, but found not guilty on grounds of insanity.

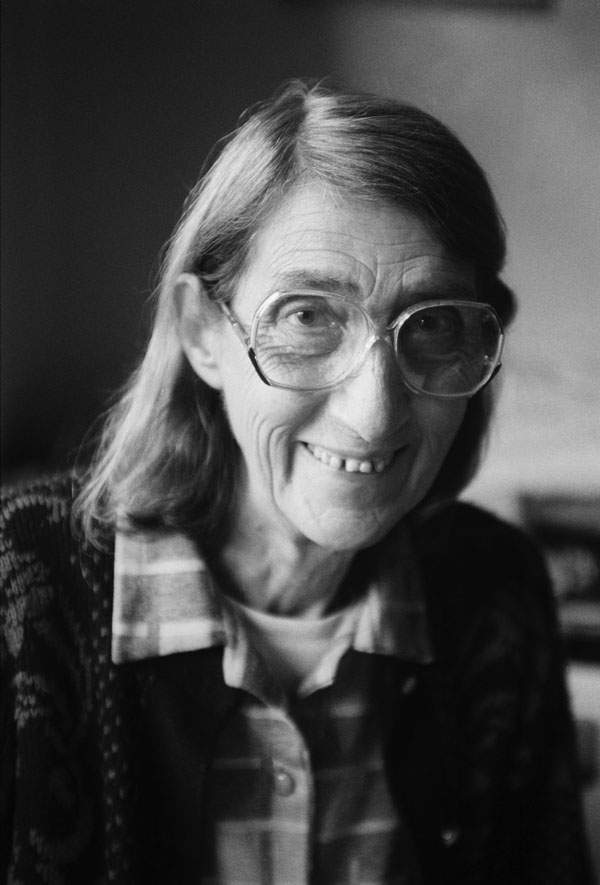

Mattan’s wife, Laura, was not informed of her husband’s execution, and only found out when she went to visit him in prison. For her, this was the start of a decades-long battle to clear his name.

“He was convinced they would find out they had made a mistake. He couldn’t speak very good English, but he kept on saying, ‘I kill no woman,’” she was quoted as saying in the Independent in 1997.

“I still believed right up to the end that they would let him go, but they didn’t, they hung him. When they did that I just locked myself away in my room with my kids, and then for some time afterwards I used to think I could see him walking down the street towards me. He was a very good husband and father. All he wanted to do was go to work and he went to sea to earn money until I was having the third child when he said he couldn’t go and leave me any more and wanted to see the boys grow up.”

Initial attempts by the family to have the conviction overturned were denied, but the case was the first to be referred to the Criminal Cases Review Commission after it was set up in the 1990s. The conviction was finally quashed in 1998. Lord Justice Rose described the case as “demonstrably flawed” noting that there was a lack of evidence – including a complete absence of forensic evidence – linking Mahmood Mattan to the murder of Lily Volpert. The family was awarded £1.4m – the first time the Home Office compensated the family of a man wrongly hanged.

Laura Mattan died 10 years later. All of his children have since died too, although some of his grandchildren and great-grandchildren still live in Cardiff.

In 1996, two years before his name was cleared, Mattan’s body was exhumed from a felon’s grave in Cardiff Prison and moved to a Cardiff cemetery.

The epitaph on his gravestone reads “KILLED BY INJUSTICE”.

By Safia Mohamed