A South African militia that claimed to be behind the murder of a UN chief was involved in deadly work across the continent, its members say

Keith Maxwell, the self-declared “commodore” of the South African Institute for Maritime Research (SAIMR), liked to dress up on special occasions in the garish costume of a 18th-century admiral, with a three-cornered hat, brass buttons and a cutlass. Ordinary members of his organisation were expected to show up in crisp naval whites.

Gathered together in upmarket restaurants, or the quiet of the Wemmer Pan naval base in south-central Johannesburg, they had the air of eccentric history buffs. Maxwell talked about the group’s roots in a Napoleonic-era treasure-hunting syndicate, and told outsiders it was still focused on deep-sea exploration.

But appearances were deceptive. Beneath the bizarre trappings lurked a powerful mercenary outfit that members claim was entwined with the apartheid state and offered soldiers for hire across the continent.

“It was clandestine operations. We were involved in coups, taking over countries for other leaders,” said Alexander Jones, who has detailed his years as an intelligence officer with the group. SAIMR’s leaders described themselves as “anti-communist” to him at the time but the group was underpinned by racism, he said. “We were trying to retain the white supremacy on the African continent.”

And among its leaders’ most dramatic claims was that it was behind the mysterious 1961 plane crash that killed UN secretary general Dag Hammarskjöld and 15 other people.

Last week the Observer revealed evidence linking an RAF veteran, Jan van Risseghem, to the tragedy. Now new documents and eyewitness accounts shed light on the alleged role of SAIMR, which claimed responsibility for the crash in secret papers and its own recruitment drives.

It is not clear if Van Risseghem, who told a friend he had shot down Hammarskjöld’s plane without knowing who was on board, had any ties to the group. Any command could have come through an intermediary.

But Jones was clear that SAIMR liked to claim ultimate responsibility for killing the UN chief. Photos of the crash site and wreckage, with purported members of the group standing nearby, featured in a presentation made to potential members when he joined three decades ago, he said.

“They didn’t tell us at that point in time that it was Hammarskjöld; they just said that they had taken out a very high-profile political opponent,” Jones told filmmakers investigating the crash.

Maxwell himself apparently also claimed SAIMR had brought down the plane, in a handwritten memoir about the group that ended up with the family of an SAIMR veteran.

Hammarskjöld’s death came amid a post-colonial race for resources in Africa. A champion of decolonisation, he made powerful enemies with his support for newly independent states and opposition to white minority rule.

On his final flight, he was heading for a secret meeting to try to broker peace in recently independent Congo. The country was on the brink of collapse after its Katanga province – key to national wealth because it held most of the country’s rich mineral deposits – declared independence. Western mining interests backed the rebels.

Jones claims he answered a SAIMR advertisement in a South African newspaper three decades ago and served for several years. He decided to speak out because he felt he needed closure and because young South Africans should know the truth.

“Anybody that resisted any white form of manipulation on the African continent, SAIMR was prepared to go and quell those for a price,” Jones said. “And that is one thing that Dag Hammarskjöld was totally against. He wanted every country for the people of that country. He was killed because he was going to change the way that Africa dealt with the rest of the world financially, and he was a threat.”

Jones was tracked down by the makers of a new documentary, Cold Case Hammarskjöld, who were looking into SAIMR because of documents handed to South Africa’s truth and reconciliation commission by the country’s National Intelligence Agency two decades ago.

Unveiled at a press conference by the commission chair, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, they purported to detail how SAIMR had masterminded the crash in coordination with UK and US intelligence services. Investigators were never able to examine the papers, though, because soon after they were returned to the archives, and the South African authorities have been unable or unwilling to retrieve the originals. The United Nations, which has reopened its investigation into Hammarskjöld’s death, has criticised South Africa for its lack of cooperation in finding the file.

Investigators have been working from poor quality photocopies of just eight documents, and for years there were questions about whether SAIMR even existed. In the UK, the Foreign Office suggested the papers were hoaxes planted by Soviet agents in a disinformation campaign, and added that British spies “do not go around bumping people off”.

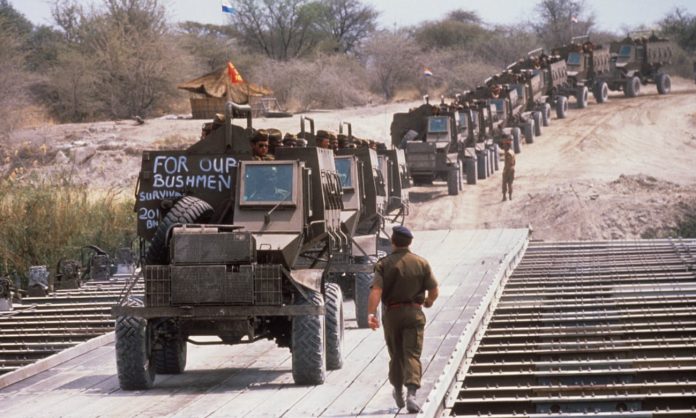

But South Africa was a known recruiting ground for mercenaries who fought in coups and conflicts across much of Africa over the second half of the last century, from Congo and Sierra Leone to Angola and Mozambique.

And over the years growing evidence of SAIMR as a real, and dangerous, entity has emerged.

Investigative journalist De Wet Potgieter interviewed Maxwell for an article in the 1990s. He took the only known picture of the “commodore”, and also collected a cache of papers from Maxwell.

Those papers included a section of his autobiography and purported lists of recruits for several operations, which the filmmakers used to track down former members. They called dozens, but only two agreed to talk.

Clive Jansen van Vuuren said he spent two or three months training with the group, which he thought had ties to the security forces. “I know it’s linked to the intelligence bureau of South Africa, but we were never given specifics,” he said.

He had kept a certificate that names him as a petty officer and carries the same slightly bizarre emblem as all other SAIMR papers – the figurehead of the British ship the Cutty Sark. But he said he never went on operations.

Jones claims to have had a more senior role, over a much longer period, and describes the group as a powerful militia. “SAIMR was not a Mickey Mouse organisation. We were not just a group of guys that got together in the weekend and decided to go do some military exercises and stuff. That was a living, breathing body,” he said.

He was recruited as an intelligence officer, after serving in a similar position with the South African armed forces, and participated in several operations. “I was definitely in the frontline: operational frontline, hand-to-hand frontline, fighting frontline. Leading operations, if you want to call it that.” Asked by filmmakers if he had killed people himself, he said “yes”.

Jones says he left SAIMR shortly before the advent of majority rule, and destroyed all evidence of his membership.

Maxwell commanded SAIMR the whole time Jones served. A strange character, charismatic and idiosyncratic, he wore naval whites at all times unless he was in his admiral’s uniform, van Vuuren, Jones and Potgieter remember. But he was also extremely dangerous. “If he didn’t like you, and if you posed a threat, he would take you out,” Jones said.

The penchant for dressing up was confirmed by a doctor, Claude Newbury, who met him through anti-abortion advocacy. He told the filmmakers Maxwell invited him to join SAIMR, describing it as a group focused mostly on hunting for lost treasure. At a private dinner, they had something “a little bit like a ceremony – he had dressed up like an admiral in the British navy from 250 years ago, with a tricorn hat, and a cutlass, and a naval uniform with lots of buttons.”

He also confirmed that Maxwell was involved in violence in South Africa, forcing a doctor who was performing abortions to leave the country.

“He went down and visited this Dutch abortionist and said to him, you are not welcome here, and killing of babies is an unacceptable pastime, and for the sake of your health I advise you go back to the Netherlands. Which apparently the chap did.”

South Africa’s former head of military intelligence, Tienie Groenewald, appears in some of Maxwell’s papers. In an interview recorded before his death in 2015, he claimed he had never heard of SAIMR but remembered meeting the “commodore”.

He described Maxwell as an intelligence operative with suspected links to foreign spies, who wanted to meet him in the dying days of apartheid to discuss an armed uprising to block the advent of democratic rule. Maxwell offered both men and arms, claiming “he had resources, to use violence, and to supply weapons, and so on and so forth”.

Although Groenewald said he declined the offer, he described Maxwell as the credible leader of a mercenary group. “He appeared to be someone who was in authority … He obviously had a background in intelligence,” he told the filmmakers. “I couldn’t prove it but I was convinced that he was financed and directed by MI6.”

Groenewald, who had served as air attache at the South African embassy in London, added: “After spending three and a half years in Britain, you get to know some people involved in the intelligence field. And certain of the names which are mentioned in our discussions were familiar to him.”

Maxwell died in 2006, but a lurid account of his life and SAIMR ended up with relatives of an ex-recruit, who shared them with the filmmakers. The handwriting matches other documents written by Maxwell and its authenticity has been attested to by Jones. Maxwell had already handed a few dozen pages of a memoir to Potgieter around 1990, and they were repeated in the new cache, but it also included over 100 pages of new material.

Some sections on SAIMR included episodes that he may not have personally witnessed – by his own account he did not join the group until 1964 – and there are some names and details are altered. Still, the episodes are described vividly, from the perspective of an eyewitness.

And one details the alleged plot to bring down Hammarskjöld – an account which matches the plan laid out in the papers revealed by Tutu. “This operation has to be arranged as an accident or a heart attack,” the commodore of the time tells his team. “Without any pathologist throwing a spanner in the works and making Dag and his colleagues into martyrs.” He asks for three workable plans to take out the UN chief.

Maxwell does not say what these were, but details a technician loading a bomb into the wheel well of Hammarskjöld’s plane in the Congolese capital Léopoldville (now Kinshasa) with a beating heart, and his frustration at watching it take off without the bomb exploding.

The memoir switches back to SAIMR’s planners, sitting round a table later that evening, disappointed by the failure of the bomb. But according to the truth and reconciliation commission’s papers, SAIMR then dispatched an “eagle” to target Hammarskjöld.

In Maxwell’s account, just as the commodore tells them to get some rest, there is a knock at the door. “A lieutenant entered, saluted and handed a slip of paper to the commodore. ‘What’s this? Oh my God, it worked’.”