Hugely popular across the African continent in the 70s and 80s, the music of Khartoum was almost extinguished in 1989 when the hard-line religious government took over. Now that rich musical heritage is available on a new compilation – Two Niles to Sing a Melody: The Violins & Synths of Sudan. Its producer, music collector Vik Sohonie, tells RFI about the golden age when singers like Mohamed Wardi packed out a 60,000-seat stadium in French-speaking Yaoundé.

The 16-song compilation features recordings from 1970 to 1997: the violin and accordion-driven orchestral music of the 70s (typical of Khartoum), the electronic music of the early 80s when Sudanese musicians experimented with synthesizers and drum machines, and the music of the 90s produced in exile.

It tells the story of a once thriving music industry that inspired a whole continent.

“I think the great testament to how greatly Sudanese music was loved around the continent was that 90% of [this album] was sourced from other countries,” Sohonie told RFI.

He and his team travelled widely to Djibouti, Ethopia, Cairo, Somalia…to collect recordings.

“Sudanese music was Sudan’s greatest export, not in a money sense but in a spiritual sense, it was the export that built the brand that Sudan was across the continent.

“So if you go to the markets in Hargeisa, the markets in Djibouti, the markets in Cairo, the markets in Addis Ababa you name it, you’re gonna find Sudanese music.

“In Cairo where we had some colleagues searching for us we found the music was still wrapped in these original plastic form, very dusty, but it was still there. And that’s a sign there was so much stock that was exported across this region. You can go all the way to Mauritania, to Mali and you will still find stocks of Sudanese music.”

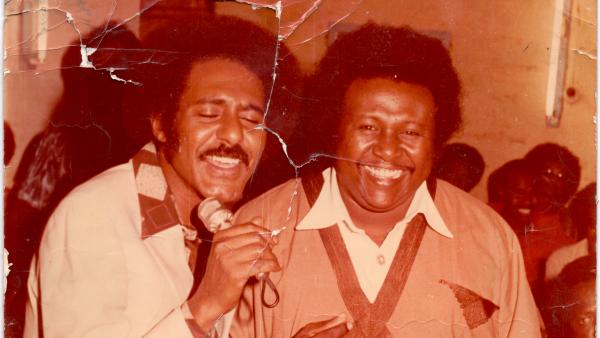

Mohammed Wardi, admired and respected across far beyond his native Nubian lands©FouadHamza Tibin/Elnour

Mohammed Wardi, admired and respected across far beyond his native Nubian lands©FouadHamza Tibin/ElnourThe last king of Nubia

The 15 singers include stars like Abdel El Aziz Al Mubarak, Kamal Tarbas, Khojali Osman and most famously Mohammed Wardi.

Wardi was, in the words of his son, ‘the last king of Nubia’ says Sohonie.

“He comes from a city that was in the ancient lands of Nubia and he brought the Nubian traditions of poetry and rhythm with him when he came to Khartoum.”

Wardi was a larger than life figure, admired and respected even in Nigeria and Cameroon, capable of selling out a 60,000-seat stadium in Yaoundé.

“You can still see the video on youtube and it’s beautiful to see; they are going crazy.”

They play like no one else

So how is it that Arab-speaking singers and musicians got such a big following in French and English-speaking Africa?

Sohonie recalls the emotional response people would often have when asked why they listened to Sudanese music from this golden age.

“An Eritrean cab driver once told me ‘the way they play is like no other’. I think he meant the way they’ve arranged the violin and accordion. It’s drawn from the orchestras of Jordan and Egypt but the way the Sudanese play the violin is not the way the Egyptians play their violins, it’s not the way Jordanians play their violins”.

The influence of politics

Many of the 16 songs are wedding songs, but some evoke political issues such as unity between north and south.

“Wardi was adored across the continent not just for his music but his political stances,” says Sohonie.

“He was a very politically active singer, believed deeply in social justice, he was someone who opposed the governments [including] the current government that’s in power today.

“Not all the singers were politically active, not all the singers were political in their lyrics,” Sohonie continues, “but they all stood in the belief of the ideas of the time, of pan-Africanism, of social justice, of decolonization, of reinvigorating local culture. They were larger than life figures. You didn’t have to understand [the songs] but you just have to listen to how they’re playing them. I think anyone can be captured by that.”

Musical clampdown

The vibrant music scene in the capital Khartoum got its first blow in 1983 with the imposition of hardline Sharia laws.

And then in 1989 when Omar al-Bashir seized power, most of the artists were targeted. They were detained, tortured and in a couple of tragic incidences [Khojali Osman] murdered.

“Music was not outright banned but it was manipulated and censored in the service of power,” Sohonie says. “Only songs that glorified Islam or glorified the many wars this government was fighting in the west and the south, were allowed. So that created a period when Sudanese musicians fled to places like Cairo and Saudi Arabia but it was particularly in places like Cairo where the music continued so in 1990s you had a host of recordings created in exile.”

Hanan Bulu Bulu, one of Sudan’s most popular young singers, ended up in exile in Cairo©Hanan Bulu Bulu

Hanan Bulu Bulu, one of Sudan’s most popular young singers, ended up in exile in Cairo©Hanan Bulu BuluWomen bore the brunt of anti-music culture

The album features two female singers: Hanan Bulu Bulu and Samira Dunia. Bulu Bulu’s performance of Alamy Wa Shagiya (my pain and suffering) was recorded live in the 1986 in Khartoum “during a small brief window when Gaafar Nimeiry’s hardline Sharia laws were kind of lessened”.

She was able to compete at the Khartoum international exhibition, a kind of competition for young talent, in 1986 and won the coveted gold award.

When, in 1989, most artists moved to Cairo Bulu Bulu stayed behind.But after being subjected to “several arrests, detention and, we read, torture she eventually decided this is enough and moved to Cairo.”

Sohonie says they would like to have included more female artists on the compilation but not only were the recordings often of poor quality but there were simpler fewer of them.

“Female artists in particular bore the biggest brunt of this anti-music clampdown. They were the ones that were specifically targeted like Hanan Bulu Bulu. They were the ones who were told ‘you should not sing, you should live a pious life devoted to religion and Islam and just forget about music’.”

They tried hard to use a recording of Hanan Alnil “one of the most beautiful voices you’ll ever hear”.

“We wanted to use one of her songs but she renounced music a long time ago under pressure from various hardline clerics, and even the national radios in Sudan are not allowed to play her music, the national TV stations are not allowed to broadcast her performances.”

While Sohonie’s co-compiler, the Sudanese former actress Tamador Sheikh Eldin Gibreel, had been very successful in getting artists to share their recordings, even she, despite being an old class-mate, could not bring Alnil around.

“She said ‘no I have renounced music, it is haram and it’s not something I want to be involved in’ and we have to respect her decision.”

Two Niles to Sing a Melody: The Violins & Synths of Sudan is out now on Ostinato Records