Abstract

Secessionist de facto states, by their very nature, sit outside of the international system. Having unilaterally declared independence from their parent state, they are invariably prevented from joining the United Nations, and thus taking their place as members of the community of universally recognised countries. While the reasons for such punitive approaches have a logic according to prevailing political and legal approaches to secession, it is also recognised that isolation can have harmful effects. Ostracising de facto can not only hinder efforts to resolve the dispute by reducing their willingness to engage in what they see as an asymmetrical settlement process, it can also force them into a closer relationship with a patron state. For this reason, there has been growing interest in academic and policy circles around the concept of engagement without recognition. This is a mechanism that provides for varying degrees of interaction with de facto states while maintaining the position that they are not regarded as independent sovereign actors in the international system. As is shown, while the concept has its flaws, it nevertheless opens up new opportunities for conflict management.

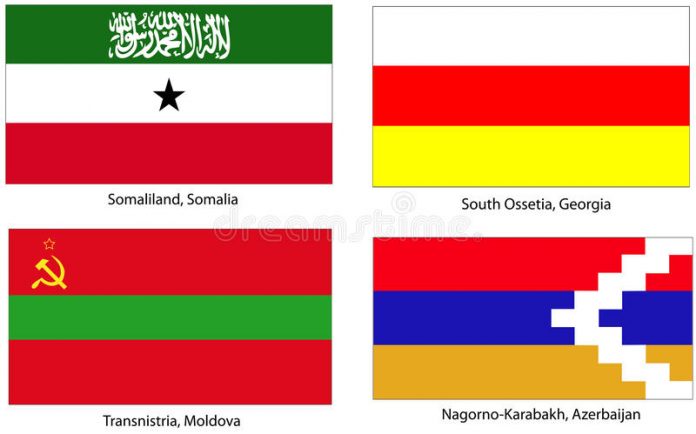

The study of de facto states—also known as contested states, unrecognised states or partially recognised states—has gained prominence in International Relations in recent years (Ker-Lindsay, 2017a; Pegg, 2017). What was once regarded as a rather marginal issue in the field has now become a growing area of interest to both scholars and practitioners. This attention has been driven by the increasing number of secessionist territories that have emerged over the past three decades. Prior to 1990, there was essentially just one separatist de facto state, the ‘Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus’ (TRNC), otherwise known as Northern Cyprus. Now a multitude of such entities exist. The end of the Cold War saw the emergence of breakaway territories across the former Soviet Union, most notably Transnistria, Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Meanwhile, the wars in the former Yugoslavia not only saw the creation of two de facto states that eventually disappeared—Republika Srpska Krajina, in Croatia, and Republika Srpska, in Bosnia and Herzegovina—it also paved the way for the unilateral declaration of independence by Kosovo. Further afield, Somaliland is perhaps the best example of a non-European de facto state. Meanwhile, more de facto states appear to be emerging. The conflict in Ukraine has seen the creation of several territories—namely the People’s Republic of Donetsk and the People’ Republic of Luhansk—that some observers, though by no means all, believe to be nascent de facto states.

With the growth of de facto states, academic attention on these entities has also blossomed. As well as the seminal literature that has defined the nature of de facto states (Bahceli, Bartman, & Srebrnik, 2004; Caspersen & Stansfield, 2011; Geldenhuys, 2009; Pegg, 1999), recent studies have sought to examine a range of other features of these entities. For example, there is a growing body of work that explores the internal political dynamics of de facto states (Broers, 2013; Caspersen, 2012; O’Loughlin, Kolossov, & Toal, 2014). However, the majority of work is still focused on the way in which de facto states interact with other actors on the world stage. While the work on how de facto states actually forge their foreign policies is rather less than one might imagine, there is a growing interest in this area (Caspersen, 2015; Comai, 2017; Ó Beacháin, Comai, & Tsurtsumia-Zurabashvili, 2016; Newman & Visoka, 2018). At the other end of the equation, rather more work is needed on the way in which the parent states try to prevent de facto states from gaining a foothold in the international system (Ker-Lindsay, 2012). Related to this, the role of major powers and supra-national bodies in the process of recognition and acceptance has also been the subject of interest by scholars (Berg & Pegg, 2018; Coggins, 2014; Ker-Lindsay, 2017b; Kyris, 2015; Relitz, 2016; Sterio, 2013). One area that has attracted considerable attention in recent years is the way in which states and international bodies can engage with secessionist territories that they do not recognise (Berg & Toomla, 2009; Lynch, 2004; Ker-Lindsay, 2015; Toomla, 2016).

The Hostility of External Environment

De facto states, by their very nature, stand outside the established international system. However, this was not always the case. At one time, the international community was willing to accept territories that had seceded and had managed to prove their objective existence as independent and sovereign states—in other words, they had proven their de facto statehood (Fabry, 2009). However, over the past 70 years, this approach has been abandoned. Since the emergence of the contemporary international system, following the end of the Second World War, there has been a fundamental shift in the way in which states respond to acts of secession. Rather than accept territories that have broken away without permission and created the structures of independent statehood, the international community has almost uniformly condemned such actions. With very few exceptions, territories that have seceded unilaterally have been ostracised by the community of sovereign states. Indeed, only one country has seceded without the permission of its parent state and eventually managed to secure membership of the United Nations. This was Bangladesh, which seceded from Pakistan in the early 1970s. Although Kosovo has managed to gain a significant degree of acceptance and is now recognised by over 110 members of the United Nations, including the United States and most of the European Union, its hopes for universal recognition, in the form of full UN membership, is curtailed by strong opposition from Russia and China. Its path to tacit international acceptance is also obstructed by leading regional powers around the world, including India, Nigeria, South Africa, Brazil and Argentina. For other secessionist territories, the picture of international acceptance has been far bleaker. Abkhazia and South Ossetia have secured a mere handful of recognitions, despite considerable lobbying Russia, by their patron. Northern Cyprus is still only recognised by Turkey. Somaliland, Transnistria and Nagorno-Karabakh are each yet to be unrecognised by a single UN member state.

In view of this hostility towards acts of unilateral secession, the international community encounters a fundamental problem when dealing with de facto states. On the one hand, there is a deep reluctance by the parent state and other external parties to interact with the authorities and institutions of a breakaway territory for fear of legitimising, if not legalising, their status. By being seen to be interacting with them too extensively, there is a danger that the impression is given that these territories are implicitly accepted. On the other hand, isolating such territories rarely leads to their demise and eventual reintegration into the state from which they have seceded. Instead, it often means that they become increasingly dependent on an external patron. It also reduces their political determination to reach a settlement as they feel that they are being as unequal parties to the dispute, both by the parent state and by the international community. As experience has shown, this punitive approach can in fact hinder efforts to reach a viable and mutually acceptable solution. To this end, it is important to try to find some sort of balance. While it is often crucial not to give the impression that the act of separatism is condoned, an overly harsh reaction can undermine settlement efforts.

Alternative to Punitive Measures

In this context, there has been a growing interest, both among scholars and practitioners, in the concept of ‘engagement without recognition’. In the policy field, the credits go to Peter Semneby, the then EU special representative for the South Caucasus. It was his brainchild, in 2009, to produce a non-paper in which he articulated the vision of interaction with breakaway territories without compromising Georgia’s territorial integrity within the post-2008 August war context (De Waal, 2017). The key point of the paper was that it sought to enhance the EU’s engagement and leverage on the regional level so that the communication channels were kept open. These ideas were also presented in a report of the EU Institute for Security Studies (Fischer, 2010) and then systematically explored in the academic literature by Cooley and Mitchell (2010).

Essentially, the concept aims to explore how various actors, including the parent state and third parties, interact with separatist entities without being seen to accept them as independent and sovereign states. The intention behind engagement has been to undermine illiberal practices and promote change, while interactions with despicable regimes or activities under unusual legal and political circumstances remain unhindered (Smith, 2005). Rather than the threat of punishment, engagement has relied on the promise of rewards to influence the target’s behaviour (Schweller, 2005). By engagement, the US, for instance, has sought to increase its leverage and footprint in conflicts which affected its national interests while at the same time not compromising with the sacrosanct principles holding up post-Second World War international legal order (Berg & Pegg, 2018).

As a tool of conflict management, ‘engagement without recognition’ can be extremely powerful. It contains both economic (trade, aid and credits) and political (implied recognition and membership) incentives; it may open up official channels of communication or remain merely at the people-to-people contact level. To many observers, it seems only logical that innovative methods of interacting with de facto states should be sought; if only to prevent de facto states from being driven ever closer into the arms of a patron state. Overall, the widespread opinion is that engagement provides alternatives to punitive policies, and therefore has become the only serious policy frame available for the accommodation of de facto states.

There are indications that some of the traditional narrative on how sovereign states deal with de facto states is ripe for revisions. Especially the conventional wisdom that de facto states are typically shunned as illegal pariahs seems to be wrong (Pegg & Berg, 2016). In reality, however, the concept of ‘engagement without recognition’ remains both under-theorised and under-analysed. Upon closer inspection, there are a whole range of issues that emerge when trying to apply the notion of engagement without recognition in practical terms. As the contributions to this volume show, interacting with de facto states is far from straightforward.

The Power of Definitions and Stigmatisation

In the opening contribution, Bruno Coppieters explores the meaning of de facto statehood. As is explained, the term ‘de facto state’ is not merely a way to describe a particular type of political entity in the international system. It goes far beyond this. The notion of ‘de facto statehood’ and the use of other terminology in the context of de facto states, such as ‘de facto authorities’ and ‘occupation’, are fundamentally normative. They are used to define the very nature of these territories as autonomous political actors in the political system. Such terms are often used to undermine their claim to full independence and statehood in the future. There can be a wide range of ways that the international community can respond to de facto states, depending on the terminology it uses and makes its actions meaningful. In order to illustrate this, the piece explores the way in which the European Union interacts with de facto states. To this end, ‘engagement without recognition’ can perhaps be thought of as a more benign outcome than the concept of ‘engagement and non-recognition’, which refers to a more prevalent state of affairs in secessionist disputes where there is a policy of collective non-recognition, but an understanding that some form of interaction, to a greater or lesser degree, can be beneficial.

Following on from this, James Ker-Lindsay explores the way in which de facto states are stigmatised within the international system and how this shapes the degree of interaction they enjoy with external actors. Given the strong opposition to secession by the international community, de facto states have often found themselves ostracised. On closer inspection, there is in fact a wide variation in the way in which de facto states engage with the outside world. This variation can be described by systemic, contextual and national factors. The systemic factors refer to the broad opprobrium attached to acts of secession and the way that this is then translated in formal international opposition. The contextual factors may include particular historical elements that might mitigate the act of secession. Finally, the national factors address the concerns of the state that is considering engagement with a de facto state. Interestingly, as is shown, the levels of stigmatisation, and therefore the degree of engagement without recognition, can change with the passage of time. To this extent, stigmatisation should be thought of as a spectrum, rather than a dividing line.

The Reception of Engagement Practices

While the position of the international community towards ‘engagement without recognition’ is crucial, the position of the parties is also vital. In her contribution, Nina Caspersen explores the very different ways in which de facto states and their parent states consider the question of engagement. The parent state is usually keen to see engagement that could pave the way for the future reintegration of the secessionist region. It will therefore focus its efforts on engagement with the population of a breakaway territory, rather than the authorities of the entity. In contrast, the de facto state will often view engagement with the parent state with considerable suspicion. It will prefer to focus instead on international engagement. These processes of external engagement are naturally viewed as a vital mechanism for underlining their self-determination and thereby securing eventual widespread acceptance and formal recognition. However, as the study shows, there is also a great deal of variation in how de facto states respond to differing forms of engagement.

Continuing on from this examination of the ways in which the parties to a conflict regard engagement practices, Eiki Berg and Kristel Vits explore the foreign policy practices of de facto states. As they highlight, de facto states try to compensate their marginal position with patron-client relations. But this creates a dilemma. While it may strengthen their position, it also undermines their legitimacy. They are not seen as actors fighting for self-determination. They are seen as mere proxies for an external power. To overcome this, they are often forced to try to engage more actively on the international stage. This presents outside actors with a problem. Do they want to cement the patron’s power over the territory by isolating the de facto state? Or do they want to break that hold, but in doing so run the risk of legitimising them, and antagonising the parent state? As the authors explore the ways in which four post-Soviet de facto states seek to engage with the wider world, they show that the avenues for international engagement are often far greater than many observers realise. In some cases, they are able to establish extensive networks of international offices. They also draw on diaspora communities. However, their attempts to reach out to the wider world can also be limited by their suspicion of the international community, which they often see as insufficiently engaged or even hostile to their existence.

The Politics of Interaction on the Supranational Level

While the goals of the de facto state and the positions of the parent state are crucial elements of the story, what really matters is the way the wider international community engages with de facto states. The next two contributions examine the ways in which international organisations interact with, and operate in, de facto states. In their piece, Vera Axyonova and Gawrich explore the role of the European Union and the Organisation for Security and Cooperation (OSCE) in the post-Soviet space. As they show, there are significant variations in the way that these bodies interact with de facto states. In trying to explain this variation of interact, the authors examine three broad factors that they feel could shape the way in which the two bodies engage with the breakaway regions. In the first instance, they point to differences in the international organisations themselves. Secondly, the exact nature of the conflict is also considered to play a significant role. Finally, the specific mandate given to the bodies in the different circumstances is examined to see if this shapes the degree of engagement they can have with the secessionist authorities. The degree and scope of engagement appear to be shaped by the length of the dispute and the probability of a return to conflict. In other words, the longer a conflict lasts, and the more frozen it becomes, the more likely it is that international actors will engage with the de facto state that has emerged.

The above-mentioned findings have particular resonance in the case of the next study. In his contribution, George Kyris examines the role of the United Nations and the European Union in Northern Cyprus. In the case of the UN, the situation is complicated by the double-hatted relationship the organisation has with the Cypriot communities for over fifty years. In the context of the settlement process, the UN Secretary-General is able to interact with the Greek and Turkish Cypriots on broadly equal terms. However, in all other contexts, the level of interaction permitted with the Turkish Cypriots is severely curtailed. In the context of the European Union, as the contribution points out, the inequality of the Turkish Cypriots is far greater. Indeed, the Greek Cypriots have often placed highly restrictive conditions on EU interaction with the Turkish Cypriots community, which has often undermined EU initiatives to help the Turkish Cypriots prepare for the demands of EU membership after a settlement. In effect, the Turkish Cypriots are frustrated about the limitations that exist in terms of any ‘engagement without recognition’ activities by the two bodies because they are forced to take into account Greek Cypriot sensitivities in a broader sense.

Mixed Conclusions

De facto states have come to prominence in international relations over the course of the past two decades. The study of de facto states is likely to develop even further in the years ahead. As is shown here, there is now a growing and vibrant community of scholars working on these issues. Within this field, the subject of ‘engagement without recognition’ has proven to be a particularly interesting area of growth in the past few years. As this volume shows, an increasingly sophisticated picture is emerging of the concept. For example, there is a very different understanding of ‘engagement without recognition’ when it refers to the actions of a parent state, and when it applies to third parties. Moreover, at the international level, the concepts of ‘engagement without recognition’ is perhaps best thought of as two different processes: one that exists where there is a fundamental split between international attitudes towards an de facto state, as in the case of Kosovo, and in those cases where the international community is largely united in its opposition to the unilateral secession of a territory. However, these forms of interaction are far from static. There is a broad range of policy reactions and these can often change according to the wider international and specific contexts of the dispute, as well as due to the vagaries of the national politics of third parties.

Meanwhile, the role of both supranational actors in international affairs is becoming more important. As shown above, the EU is playing a significant role in the existence of de facto states, providing a mechanism for engagement that circumvents the individual recognition of its member states. At the same time, the role of city diplomacy is being increasingly recognised as a key element of contemporary international affairs. In this sense, this type of interaction could offer some interesting insights into the future of de facto states. On the one hand, their ability to engage with non-state actors may make formal engagement with UN recognised states less important than in the past. However, it may also offer up an alternative vision of de facto states reintegrating into their parent states but being able to enjoy more external autonomy than would have been the case in the past. In this context, we may be seeing a third paradigm emerging: ‘engagement with no need for recognition’ (Acuto, 2016).

At the same time, the concept of ‘engagement without recognition’ is not free from certain flaws which have negative policy implications. First, the issues of sovereignty and territorial integrity are particularly pertinent to the international community. Engaging with de facto states may be seen as a violation of the sacrosanct principles of international law. Thus, if not in words then in deeds, parent states are more often in favour of non-recognition practices and therefore do not see an easy match with an engagement strategy which sets their monopoly over sovereignty in doubt. Second, the non-permissive legal and political environment stigmatises breakaway territories as occupied and under the control of an illegitimate regimes. This provides a fertile ground for enacting legislation which criminalises unauthorised visits and contacts with de facto authorities or civil society organisations. This poses serious obstacles to confidence building: without good intentions, engagement can hardly materialise. Third, the engagement strategy may be rejected on the grounds that it usually offers merely a fraction of what de facto states get from their patrons in the form of financial assistance and security. At the same time, all contacts and collaborative proposals with the rest of the world are supposed to go through parent states’ capitals, which makes de-isolation exclusively linked with the settlement of the conflict, seen as reintegration in the eyes of de facto authorities.

Whether positively loaded ‘engagement’ overweighs negatively perceived ‘non-recognition’ is a question which invites both policy-makers and academics to critically examine the content of this special issue. As our understanding of the concept evolves, the ways in which this tool of conflict management can be better used to tackle protracted secessionist conflicts will improve.

Acknowledgements

This volume emerged from the annual conference at the Institut für Ost- und Südosteuropaforschung (IOS), Regensburg, 30 June–2 July 2016: ‘Breaking the Ice of Frozen Conflicts? Understanding Territorial Conflicts in East and Southeast Europe’. We would like to extend our sincerest appreciation to Tanja Tamminen, Sebastian Relitz and the other members of the IOS for their instrumental role in making this publication possible.

References

- Acuto, M. (2016). City diplomacy. In C. M. Constantinou, P. Kerr, & P. Sharp (Eds.), The Sage handbook of diplomacy. CA: Sage.

,

- Bahceli, T., Bartman, B., & Srebrnik, H. (Eds.). (2004). De facto states: The quest for sovereignty. London: Routledge.

- Berg, E., & Pegg, S. (2018). Scrutinizing a policy of “engagement without recognition”: US requests for diplomatic actions with de facto states. Foreign Policy Analysis, 14(3), 399–407.

- Berg, E., & Toomla, R. (2009). Forms of normalisation in the quest for de facto statehood. The International Spectator, 44(4), 27–45. doi: 10.1080/03932720903351104

,

- Broers, L. (2013). Recognising politics in unrecognised states: 20 years of enquiry into the de facto states of the South Caucasus. Caucasus Survey, 1(1), 59–74. doi: 10.1080/23761199.2013.11417283

,

- Caspersen, N. (2012). Unrecognized states. London: Polity.

- Caspersen, N. (2015). The pursuit of international recognition after Kosovo. Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 21(3), 393–412.

,

- Caspersen, N., & Stansfield, G. (Eds.). (2011). Unrecognized states in the international system. London: Routledge.

- Coggins, B. (2014). Power politics and state formation in the twentieth century: The dynamics of recognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

,

- Comai, G. (2017). The external relations of de facto states in the South Caucasus. Caucasus Analytical Digest, 94, 8–14.

- Cooley, A., & Mitchell, L. (2010). Engagement without recognition: A new strategy toward Abkhazia and Eurasia’s unrecognized states. Washington Quarterly, 33(4), 59–73. doi: 10.1080/0163660X.2010.516183

,

- De Waal, T. (2017). Enhancing the EU’s engagement with separatist territories. Carnegie Europe. Retrieved from http://carnegieeurope.eu/2017/01/17/enhancing-eu-s-engagement-with-separatist-territories-pub-67694

- Fabry, M. (2009). Recognizing states: International society and the establishment of new states since 1776. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fischer, S. (2010). The EU’s non-recognition and engagement policy towards Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Brussels: European Union Institute for Security Studies.

- Geldenhuys, D. (2009). Contested states in world politics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

,

- Ker-Lindsay, J. (2012). The foreign policy of counter secession: Preventing the recognition of contested states. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

,

- Ker-Lindsay, J. (2015). Engagement without recognition: The limits of diplomatic interaction with contested states. International Affairs, 91(2), 267–285. doi: 10.1111/1468-2346.12234

,

- Ker-Lindsay, J. (2017a). Secession and recognition in foreign policy, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

,

- Ker-Lindsay, J. (2017b). Great powers, counter secession, and non-recognition: Britain and the 1983 unilateral declaration of independence of the “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus”. Diplomacy & Statecraft, 28(3), 431–453. doi: 10.1080/09592296.2017.1347445

,

- Kyris, G. (2015). The Europeanisation of contested statehood. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Lynch, D. (2004). Engaging Eurasia’s separatist states: Unresolved conflicts and de facto states. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press.

- Newman, E., & Visoka, G. (2018). The foreign policy of state recognition: Kosov’s diplomatic strategy to join international society. Foreign Policy Analysis, 14(3), 367–387.

- Ó Beacháin, D., Comai, G., & Tsurtsumia-Zurabashvili, A. (2016). The secret lives of unrecognised states: Internal dynamics, external relations, and counter-recognition strategies. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 27(3), 440–466. doi: 10.1080/09592318.2016.1151654

,

- O’Loughlin, J., Kolossov, V., & Toal, G. (2014). Inside the post-Soviet de facto states: A comparison of attitudes in Abkhazia, Nagorny Karabakh, South Ossetia, and Transnistria. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 55(5), 423–456. doi: 10.1080/15387216.2015.1012644

,

- Pegg, S. (1999). International society and the de facto state. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Pegg, S. (2017). Twenty years of de facto state studies: Progress, problems, and prospects, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

,

- Pegg, S., & Berg, E. (2016). Lost and found: The WikiLeaks of de facto state–great power relations. International Studies Perspectives, 17(3), 267–286.

,

- Relitz, S. (2016). De facto states in the European neighbourhood: Between Russian domination and European (dis)engagement. The Case of Abkhazia. EURINT Proceedings, 2016. Retrieved from http://cse.uaic.ro/eurint/proceedings/index_htm_files/EURINT%202016_REL.pdf

- Schweller, R. L. (2005). Managing the rise of great powers: History and theory. In A. I. Johnston & R. S. Ross (Eds.), Engaging China: The Management of an Emerging Power (pp. 1–31). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Smith, K. E. (2005). Engagement and conditionality: Incompatible or mutually reinforcing. In R. Youngs (Ed.), Global Europe: New terms of engagement (pp. 23–29). London: The Foreign Policy Center.

- Sterio, M. (2013). The right to self-determination under international law: “Selfistans”, secession and the rule of the great powers. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Toomla, R. (2016). Charting informal engagement between de facto states: A quantitative analysis. Space and Polity, 20(3), 330–345. doi: 10.1080/13562576.2016.1243037 Taylor & Francis Online]

By James Ker-Lindsay & Eiki Berg

![]()