China’s two-child policy is having unintended consequences

THE one-child-per-couple policy was horrific for women in China. Many were subjected to forced sterilisations or abortions. Newborn girls were killed, removed by family-planning officials or abandoned by parents desperate that their one permitted baby be a boy. Women from neighbouring countries suffered, too, as victims of human trafficking; a skewed sex-ratio made it more difficult for young men to find Chinese wives. So the government’s announcement in late 2015 that it was relaxing the policy, after 35 years, was good news. Yet the two-child-per-couple policy that replaced it may bring different kinds of problems.

For a generation the government assured women that “one is enough” and that “late marriage and late childbirth are worthy.” Now state media urge them to marry while still in university and remind them that older mothers are more likely to have babies with birth defects, notes Leta Hong Fincher, an author and academic. Officials are encouraging childbirth because they worry that the fertility rate (the number of children a woman can expect to have during her lifetime) has sunk well below 2.1, the level required to keep the population stable in the long term. They fear a shrinking population will hamper economic growth.

The birth rate increased slightly in 2016 but fell again last year. Rumours suggest that the two-child policy could itself be tossed out soon, allowing couples to have as many kids as they like. Families would doubtless appreciate less meddling from government, but the reform is unlikely to produce very many more babies. Many couples do not want more children because they cannot afford to pay more for housing, health care and education. Decades of being told that small families are glorious has not helped. Helen Gao, a 30-year-old writer who works at China Policy, a think-tank in Beijing, says that having one child has become an ideal in China, just as some Americans might regard a couple with two children and a dog as the perfect-sized unit.

The loosening of family-planning rules is also creating new problems for women. In the past, bosses knew that female staff would take paid maternity leave only once. Now they fret about having to shell out multiple times. A survey by 51job.com, an employment website, found that 75% of companies were more reluctant to hire women after the two-child policy took effect. Another, by the All-China Women’s Federation, found that 55% of women had been asked personal questions in job interviews, such as: “Do you have a boyfriend?” or “When do you plan to have children?”

Providing maternity leave has become more costly for employers. Over the past two years most Chinese provinces have extended paid leave beyond the 98-day minimum mandated under national law, hoping this will encourage more families to have a second child. China has laws against sex discrimination, including a rule that bars firms from firing pregnant women until their child is at least one year old, but enforcement is lax. Executives have “zero fear” of punishment, says Sophie Richardson of Human Rights Watch.

In a survey carried out last year by Zhaopin, a jobs website, a third of women reported that their wages fell after giving birth (though for some this may be because they worked fewer hours). Some 36% said they were demoted. At an arbitration court in Beijing, a mother who gives her name as Xiao Wei recently secured a small settlement from a state-owned firm that she says treated her and other pregnant women unfairly. But she says finding a new job while her seven-month-old son is still breastfeeding is likely to be a “hopeless cause”.

Meanwhile the government is gradually implementing policies that look as if they could be intended, at least in part, to increase the birth rate. In June the southern province of Jiangxi became the latest of several local authorities to say that it would start requiring women who are more than 14 weeks pregnant to secure the approval of three doctors in order to procure an abortion. (Such policies are ostensibly aimed at preventing the termination of unwanted girls, but cynics think they could be used to drive up births more broadly.) Health officials have taken to discouraging women from having Caesarean sections, arguing that they increase the risk of complications during a second pregnancy. Chinese courts are also beginning to tighten divorce rules by enforcing “cooling-off” periods after applications are filed—including, say critics, in some cases where a woman’s safety might be at risk. Whether the government is restricting family sizes or trying to boost them, “it is always about control,” says Mei Fong, a journalist and the author of “One Child”, a book about China’s family-planning policies.

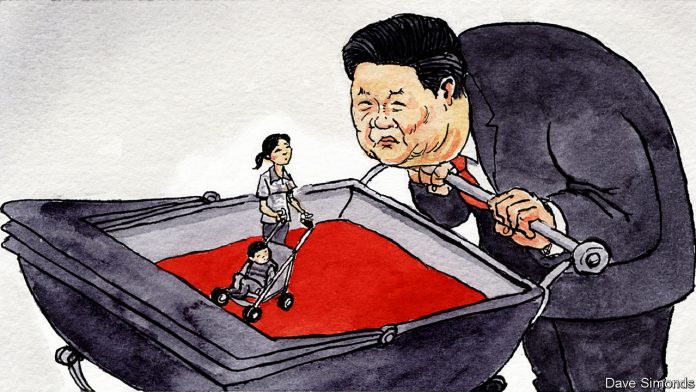

China’s leader, Xi Jinping, talks of his “commitment to gender equality and women’s development”. But since he came to power in 2012, China’s ranking in the World Economic Forum’s global index of gender parity has fallen from 69th to 100th, above Malawi and India but below Cambodia and Brazil. Women’s participation in the workforce is high compared with many Asian countries but is slowly declining; the wage gap has widened too. Like his predecessors, Mr Xi has not appointed any women to China’s highest political body, the Politburo Standing Committee. The authorities have stepped up their repression of civil society. This has included the jailing of feminist activists and the shutting down of the most prominent women’s-rights blog (this took place on International Women’s Day).

If Mr Xi wants women to have more children, he should make it easier for them to do so. A good start would be to enforce anti-discrimination laws and to boost investment in child care. Sometimes fawningly called “Big Daddy Xi”, the president might justify the moniker if he better cared for his country’s daughters.