Internment camps with up to a million prisoners. Empty neighborhoods. Students, musicians, athletes, and peaceful academicsjailed. A massive high-tech surveillance state that monitors and judges every movement. The future of more than 10 million Uighurs, the members of China’s Turkic-speaking Muslim minority, is looking increasingly grim.

As the Chinese authorities continue a brutal crackdown in Xinjiang, the northwest region of China that’s home to the Uighur, Islam has been one of the main targets. Major mosques in the major cities of Kashgar and Urumqi now stand empty. Prisoners in the camps are told to renounce God and embrace the Chinese Communist Party. Prayers, religious education, and the Ramadan fast are increasingly restricted or banned. Even in the rest of China, Arabic text is being stripped from public buildings, and islamophobia is being tacitly encouraged by party authorities.

But amid this state-backed campaign against their religious brethren, Muslim leaders and communities around the world stand silent. While the fate of the Palestinians stirs rage and resistance throughout the Islamic world, and millions stood up to condemn the persecution of the Rohingya, there’s been hardly a sound on behalf of the Uighur. No Muslim nation’s head of state has made a public statement in support of the Uighurs this decade. Politicians and many religious leaders who claim to speak for the faith are silent in the face of China’s political and economic power.

“One of our primary barriers has been a definite lack of attention from Muslim-majority states,” said Peter Irwin, a project manager at the World Uyghur Congress. This isn’t out of ignorance. “It is very well documented,” said Omer Kanat, the director of the Uyghur Human Rights Project. “The Muslim-majority countries governments know what’s happening in East Turkestan,” he said, using the Uighur term for the region.

Many Muslim governments have strengthened their relationship with China or even gone out of their way to support China’s persecution. Last summer, egypt deported several ethnic Uighurs back to China, where they faced near-certain jail time and, potentially, death, to little protest. This followed similar moves by Malaysia and Pakistan in 2011.

This is in stark contrast to how these countries react to news of prejudice against Muslims by the West or, especially, Israel. Events in Gaza have sparked protests across the Islamic world, not only in the Middle East but also in more distant Bangladesh and Indonesia. If Egypt or Malaysia had deported Palestinians to Israeli prisons, the uproar would likely have been ferocious. But the brutal, and expressly anti-religious, persecution of Uighurs prompts no response, even as the campaign spreads to the Uighur diaspora worldwide.

Part of the answer is that money talks. China has become a key trade partner of every Muslim-majority nation. Many are members of the Chinese-led Asian Infarastructure investment Bank or are participating in China’s Belt and Road Initiative. In South Asia, this means infrastructure investment. In Southeast Asia, China is a key market for commodities such as palm oil and coal. The Middle East benefits due to China’s position as the world’s top importer of oil and its rapidly increasing use of natural gas.

“Many states in the Middle East are becoming more economically dependent on China,” said Simone van Nieuwenhuizen, a Chinese-Middle East relations expert at the University of Technology Sydney. “China’s geoeconomic strategy has resulted in political influence.”

“I don’t think there is a direct fear of retribution or fear of pressure,” said Dawn Murphy, a China-Middle East relations expert at Princeton University. “I do think that the elite of these various countries are weighing their interests, and they are making a decision that continuing to have positive relations with China is more important than bringing up these human rights issues.”

Xinjiang’s immediate neighbors, such as Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Kazakhstan, face a particularly difficult situation. The ongoing persecution has caught up some of their own citizens, or their families. But with both close economic and geopolitical ties to China, these countries are highly reluctant to speak up. Pakistan sees China as a vital balancer against India, and their relationship, sometimes referred to as the “iron brotherhood,” goes back decades.

But there are subtler reasons the Uighur are ignored. They are on the edge of the Muslim world, in contrast to the Palestinian cause, which is directly connected to the fate of one of Islam’s holiest cities, Jerusalem. China has little place in the cultural imagination of Islam, in contrast with Muslims’ fraught relationship with the idea of a Jewish state. Even as China’s presence in the Middle East grows, it lacks the looming presence of the United States or Israel.

China’s success at cutting off access to Xinjiang is another reason. A regular dose of videos depicting Palestinian suffering hits YouTube every day. Interviews with tearful Rohingya stream on Al Jazeera and other global media outlets. Palestinian representatives and advocates speak and write in the media. But few images are emerging from Xinjiang due to restrictions on press access and the massive state censorship apparatus. That means the world sees little more than blurry satellite footage of the internment camps. Even Uighurs who have escaped are often only able to talk anonymously, not least because Chinese intelligence regularly threatens persecution of their families back home if they speak up.

It’s also much harder to stir up feelings about a new cause rather than an old, established one. For leaders who care more about their own popularity than human rights, it’s an easy call. “People tend to pay more attention to this kind of issue,” said Ahmad Farouk Musa, the director of the Malaysian nongovernmental organization Islamic Renaissance Front. “You gain popularity if you show you are anti-Zionism and if you are fighting for the Palestinians, as compared to the Rohingya or Uighurs.”

There are two places, however, where there may be hope for leadership. One is Southeast Asia, where Indonesia and Malaysia are two of the Islamic world’s few democracies. Both have relatively a free press, have an active civil society, and, importantly, are geographically close to China, giving the giant country more of a presence in the local public consciousness. Anti-Chinese feeling is strong in both nations, especially Indonesia.

Malaysia bears watching due to its recent historic election. China was a key campaign issue, due to its connection to the massive, multibillion-dollar 1MDB scandal. The new government is taking a strong position on China, with the new finance minister, Lim Guan Eng, pledging to review all of China’s trade deals with the country and suspending several existing projects.

“The Chinese had been very influential in giving loans to [former Prime Minister] Najib [Razak] to stay in power, so they felt compelled to accept whatever the Chinese wanted them to do,” Musa said. “I hope that the new government has shifted their policy and will become more sensitive towards this issue and about human rights.”

The first test of this will happen soon, as the Chinese government is demanding the deportation of 11 Uighur asylum-seekers from Malaysia. The new government, led by Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, may not be as willing to bend to China’s demands as the previous one.

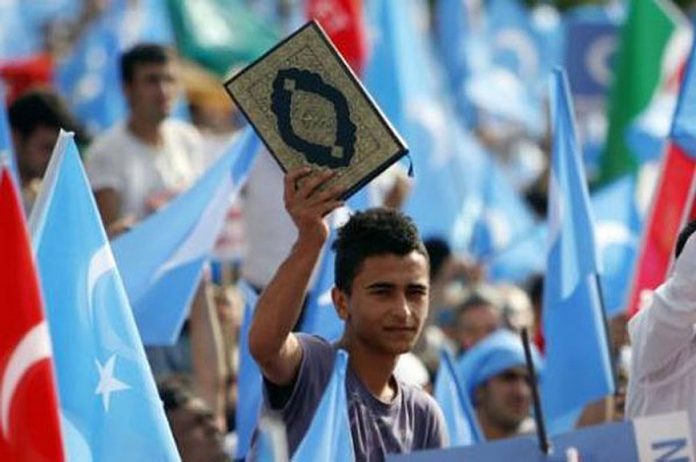

The other place to watch is Turkey, which has a strong cultural connection to the Turkic-speaking Uighurs and is home to the largest Uighur exile community. In 2009, when riots broke out in Urumqi, only Turkey’s leader, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, spoke out. Turkey has also seen the only widespread protests against China’s treatment of Uighurs, most recently in 2015.

“Turkey is the only major country whose leadership as well as the public is widely aware of the Uighur persecution in East Turkestan,” said Alip Erkin , a Uighur activist currently living aboard.

But Turkey’s growing authoritarianism has caused it to look toward China as a possible ally against the West. Since Turkey’s Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu visited China last year and said his country would eliminate “anti-China media reports,” there has been less attention given to the Uighur cause, including on the streets. Still, many Uighurs hold out hope.

“Many Uighurs think Turkey can be the ultimate defender of the Uighur cause when the time is right,” Erkin said.

While the signs of hope are there for the Uighur cause, they are small and localized. China’s profile is growing, and more Muslim-majority nations are becoming dependent on its economic power—earlier this month, $23 billion in loans was promised to Arab states. The chances of a unified Muslim response to the Uighur human rights crisis are getting slimmer and slimmer.