As countries across the Horn of Africa embark on ambitious programs to attract foreign investment, Djibouti seems a stable option in a volatile region. But there are risks, according to a new report by political and security risk consultancy Allan & Associates.

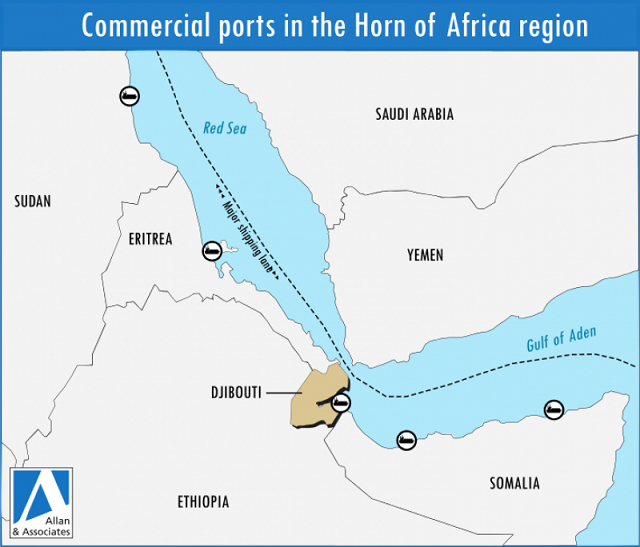

Djibouti, which is seeking to become a Horn of Africa trans-shipment hub, has proved attractive to investors in recent years. Located near some of the world’s busiest shipping lanes, with access to the Indian Ocean and Red Sea, it can boast decades of peace and political stability, unlike neighbors that include divided Somalia, secretive Eritrea and war-torn Yemen.

Djibouti is bordered by Eritrea in the north, Ethiopia in the west and south, and Somalia in the southeast. The remainder of the border is formed by the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden at the east. It occupies a total area of just 23,200 square kilometers (8,958 square miles).

“Djibouti offers an attractive environment for investors in the Horn of Africa, but be careful how you tread,” says Allan & Associates Senior Analyst and Sub-Saharan Africa specialist Olivier Milland, author of the report. Significant investment risks include:

• Growing corruption concerns as the country has slipped in international indices for transparency and governance

• Regional competition for contracts may see national elites attempt to access rents from foreign investors

• Poor macro-economic indicators, with public debt reaching 87 percent of GDP in 2018

• Over-dependence on neighbor Ethiopia – 95 percent of Ethiopian exports pass through the port of Djibouti – and China, its top source of foreign investment

• Vulnerability to a global pro tectionist trend, driven by U.S. President Donald Trump, due to a reliance on port traffic

tectionist trend, driven by U.S. President Donald Trump, due to a reliance on port traffic

• Rifts between Gulf countries threaten stability of investments

• Concerns over renegotiation of contracts under a new law and localization

African governments are exposed to mounting popular pressure to ensure that development favors the local population. From Ghana in west Africa to Tanzania in the east, African governments are renegotiating contracts with foreign investors that were signed by previous administrations. For example, in Ghana the new government sought to renegotiate the terms of a construction contract with UAE-based Ameri Group, arguing the gas turbines it had ordered were overpriced. In Nigeria, authorities are increasingly under pressure to award public tenders to local businesses over foreign contractors. This includes the development of the port in the commercial hub Lagos.

These policies coincide with mounting levels of public debt, which are likely to pose liquidity risks in the medium term. To fund such infrastructure projects governments need access to large loans, many of which are provided by Exim Bank of China, increasing their dependence on China for the future development of their infrastructure.

Last year, China replaced the U.S. as Djibouti’s top source of foreign investment. In 2012, the government ceded 23.5 percent of Djibouti Doraleh Multi-Purpose Port to China Merchants Holdings (International), a Hong Kong-listed Chinese state-owned entity.

Djibouti currently has three main infrastructure projects in the pipeline with China; all three are likely to play key roles in China’s Belt and Road project. Additionally, Singapore-based contractor Pacific International Lines, which is a member of a Belt and Road consortium of companies, signed an agreement with the government in March to develop Doraleh Container Terminal in Djibouti and increase the volume of cargo handled at the port by one third.

Djibouti is heavily dependent on Ethiopia as 95 percent of Ethiopia’s export goods pass through the port of Djibouti. Consequently Ethiopia can exert political pressure against its neighbor, for instance by moving to diversify its port traffic to new deepwater projects in countries such as Kenya, or as more recently seen in Ethiopia’s decision to buy a 19 percent stake in the port of Berbera in Somaliland.

Changing geopolitical dynamics in the region, amid protectionist policies in the U.S. and a rift between the Gulf countries, are posing additional challenges to investors – particularly from China and the Gulf – who will face political pressures to renegotiate contracts if authorities see an opportunity to gain more revenue from other financiers. The government’s seizure in February 2018 of the Doraleh Container Terminal (DCT) from DP World highlighted the country’s erratic policy environment. The government claimed that the conditions under which the concession was signed contravened state sovereignty. The case is currently being heard by the London Court of International Arbitration in the U.K.

Court judgment from a high court in London in 2014 ruled that the allegations by the government were unfounded. Despite the court’s ruling, Djibouti proceeded with its seizure in February.

This was not the first time that the authorities unilaterally had terminated a contract with foreign investors. In 2014, the Djiboutian authorities canceled the contracts of Oil Libya and two subsidiaries linked to French energy group Total after the companies refused to pay fines relating to alleged pollution in the port of Djibouti.

Djibouti is not a signatory to the World Bank’s International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes. Given the authoritarian nature of the government, the level of opacity in business transactions is likely to continue to expose companies to corruption and compliance risks.

Djibouti faces competition to the east from Somaliland, a self-declared autonomous state in north-western Somalia that is developing its port at Berbera, and Sudan to the west, which plans to sell stakes in the management of Port Sudan, the country’s only commercial port, on the Red Sea.

![]()