And that’s got to change

Every morning, 28-year-old Officer Shamis Abdi Bile rises before dawn to make breakfast for her husband and three young children.

Every morning, 28-year-old Officer Shamis Abdi Bile rises before dawn to make breakfast for her husband and three young children.

She bustles around the house, fulfilling the traditional role of homemaker, something that is still expected of Somali women. But once her family has eaten, Bile takes on an unexpected role.

Bile becomes a warrior; almost single-handedly fighting for the prosecution of rape and sexual violence in Puntland, Somalia.

She changes into her khaki police uniform, neatly pressed and spotless, and walks several miles through the dusty streets of Garowe — the small capital city of Somalia’s vast, barren Puntland state — to the local police station.

Bile is the only female officer in her unit, and the only woman handling issues of sexual violence in the area.

Waiting for Bile in the hot, stuffy interview room is a terrified teenage girl. She grips the hands of her friend so tightly that her knuckles turn white.

The girl’s angry sobs are barely audible over the sound of dozens of flies buzzing around the tiny space. It has no doors or windows to ensure privacy; any number of the men in the office will be able to overhear the girl’s testimony.

A young boy from her neighbourhood held her down for the purpose of raping her, tearing at her clothes as she screamed.

The girl has been once to the police station already, several days ago, but when she tried to report the crime, nobody seemed to care.

Instead, the male officers mocked her, advising her to go home and forget about it because she would not find the justice she was seeking.

This is why Bile gets up every morning and goes to a job that can barely pay her a living wage (she hasn’t been properly paid in a year). She’s furious, and she’s the only one determined to help.

‘I feel driven to help when a woman is being abused,’ Bile says passionately. ‘And do whatever I can do to catch those who are harassing her.’

The girl’s dark eyes glint as she keeps the rest of her face covered. She won’t give her name, afraid that being labeled a rape survivor in Somalia’s ultra-conservative society would ruin her and her family’s reputation.

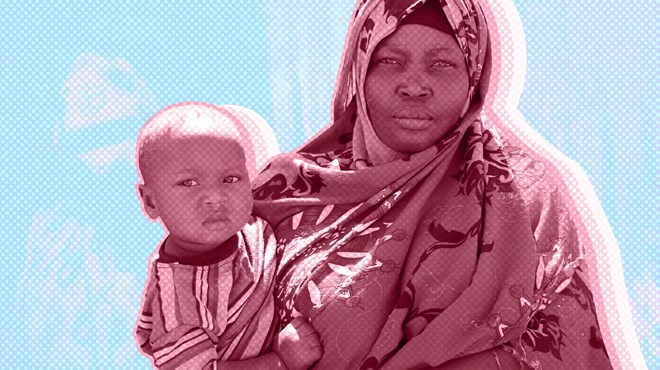

Shamis Abdi Bile – a police officer on a mission to change life for women in Somalia NEHA WADEKAR

Bile, a fierce and unconventional woman, summons the male colleague originally assigned to the case into her office for a public scolding, stamping her neon orange sneakers and bellowing loudly.

She doesn’t care that the officer outranks her, nor that here, in Somalia, his status as a man makes him her social superior. She may be the only female officer, but she commands the respect of the men around her.

As Bile berates him, the male officer places his hands on his portly belly and tries to look ashamed. He attempts to defend himself, weakly protesting that the teenage girl would be better off if she just forgot the incident altogether. After all, he says, rape is common here and nobody takes that sort of thing seriously. Nobody, it seems, except Officer Bile.

Brimming with frustration, Bile promptly takes over the case.

‘Some officers say rape is not a big deal,’ Bile says. ‘They say it has been happening for ages and it’s nothing new.’

Rape Is Commonplace

Welcome to Somalia, the place where rape is so common that many don’t even consider it a crime at all. Here, almost every woman has a #metoostory, but little means of fighting for justice. Here, violence against women makes up 30 per cent of reported crimes in Somalia, according to the United Nations.

But the real number is likely so much higher.

Decades of civil war and violence in Somalia have crippled the government institutions responsible for protecting citizens. There’s no money to pay the salaries of police officers, judges and lawyers, so corruption and inefficiency are rampant. Men and boys accused of rape often pay a small sum for police officers or judges to look the other way. It is extremely rare that a rape case will be granted a proper investigation. As a result, crimes involving sexual violence in Somalia are rarely reported because women have little faith in the government’s ability to get justice.

’The men will say, ‘those women are problem seekers and [liars], saying that men have raped them when it is not the truth,’’ Bile says.

Sometimes male officers accuse women of lying and demand proof that she doesn’t have, to validate her story. Other times, they blame the victim, asking what clothes she was wearing or what she said to the man to cause the rape. More often than not, though, they tell her that rape happens and she should get over it and move on.

These stories are so common that most women decide they’d rather keep silent than face the humiliation and abuse of telling their stories to the police.

Officer Bile is a force of life and leads an astonishing charge for women in the region to take matters into their own hands, to protect other women around them. She is working to change things for women who have been raped, so that they can finally get the justice they deserve.

‘The policemen like to defend the men, just as I like to protect the women’s rights,’ Bile says with a cheeky smile.

Fighting All The Way Up

She was born around 1989, two years before the start of the civil war. The daughter of a policeman, she dreamed of following her father’s footsteps and joining the force. But there were obstacles. Like many women in Somalia, Bile never finished school, dropping out to help her mother take care of the family.

Bile married a police officer when she was still a teenager, and the couple had three children. But when her husband took a second wife, Bile took her children and left him. She enrolled in the police academy, and — thanks to emerging and recent efforts by global organisations like the UN to increase women’s participation in security — she graduated.

Officer Bile NEHA WADEKAR

Officer Bile NEHA WADEKAR

During her training in the police academy, Bile was one of only 80 women in a class of 800. One female for every 10 male officers is a small percentage; in the UK, it’s closer to three females for every 10 male officers.

Somalia’s conservative culture considers women unfit for the violence and rigors of police work. But Bile’s fierce, no-nonsense personality and talent has earned her the respect of her male colleagues, who often ask for her help on cases involving women.

Bile even knows how to shoot — she learned at the police academy — but the police station has limited weapons available and as a woman, Bile is the lowest priority.

‘She doesn’t need one,’ her superior officer jokes. ‘I’m her bodyguard.’ Bile rolls her eyes, smiling with practiced patience.

‘Those men cannot force me to do anything,’ she says.

Bile became the first female officer in Garowe to join the police’s criminal investigation division when she was promoted to its newly-established women’s crimes desk late last year.

Making All The Difference

For women who have been raped, having a woman officer like Bile who treats them with compassion makes all the difference.

She fights for women like Hawa Omer Shabelle, who fled from extremists terrorising her home in southern Somalia.

Her newborn baby died on the journey.

When she arrived in Puntland, Shabelle remarried, but her new husband soon turned out to be violent and abusive. Officer Bile helped Shabelle escape her marriage and get a divorce.

When Shabelle was then brutally raped by two strangers, she turned to Bile for help a second time. The police caught the rapists, but the case never made it to court. Instead, it was settled through ‘xeer,’ Somalia’s clan-based dispute resolution system in which traditional male elders dispense justice according to customary laws.

Hawa Omer Shabelle was raped and stabbed by two men NEHA WADEKAR

Usually, the rapist’s family pays a ‘diya,’ a fine of money, camels or goats, to the survivor’s family, and the case is considered closed. In extreme scenarios, the survivor is forced to marry her rapist. Most cases of rape and sexual assault in Somalia are still settled through this ancient system.

But thanks to advocates like Bile, things are starting to change for women who have been raped in Puntland.

The Future Is Brighter

In 2017, Puntland became the first region to pass a Sexual Offences Act, criminalising all forms of sexual violence against women and imposing harsh penalties: five to fifteen years of jail time and the death penalty for cases when a woman dies as a result of the rape or attack.

The new law was developed using a combination of international human rights standards, Islamic Sharia law and the xeer system of justice. It’s not perfect — there is still no provision to protect wives who have been raped by their husbands — but it’s a start.

Puntland’s Ministry of Justice says the law is already making a difference. Last year, roughly 54 per cent of rape and sexual violence cases resulted in court convictions — a major improvement from the past, when very few cases made it to court and even fewer resulted in convictions.

In 2017, Somalia also opened its first forensic laboratory, dedicated to testing DNA from rape cases in the city of Garowe. In Puntland, the Attorney General’s office has trained ten female lawyers to serve as experts in cases of rape and sexual violence, and the police have established new women’s crimes desks in police stations across the region.

The sweeping changes include an effort to recruit more women police officers, like Officer Bile.

These new initiatives have created a strong foundation for change, but there are still challenges, primarily lack of funding. The government needs to better train police, judges and lawyers. The forensic laboratory is still missing a key piece of equipment to become fully operational. And the police need more resources — including vehicles, computers, rape kits, and salaries — in order to investigate properly.

Bile hopes the government’s efforts to raise money dedicated to the protection of women in Puntland will give police officers more resources for training and equipment to deal with rape cases.

She hopes the money will mean she gets a regular paycheck — she needs one to support her family now that she’s become the sole provider for her three young children, her parents, and ten other family members who live with her.

Change is coming to Somalia, Bile says, and not just in the police department.

As a modern Somali woman and a working mother, Officer Bile is unabashed about her own dreams. She’s fighting for a new Somalia for women: someday, she says, she’ll head up Garowe’s criminal investigation unit herself.

And then, she’ll take on Somalia’s entire male-dominated police force, with the force and wit that defines her.

By NEHA WADEKAR

‘The Warriors’ is a year-long reporting project by ELLE and the Fuller Project for International Reporting, funded by the European Journalism Centre via its Innovation in Development Reporting Grant Programme