A new report details how Ethiopia targeted advocates of the Oromo ethnic group across 20 countries infecting their computers with spyware

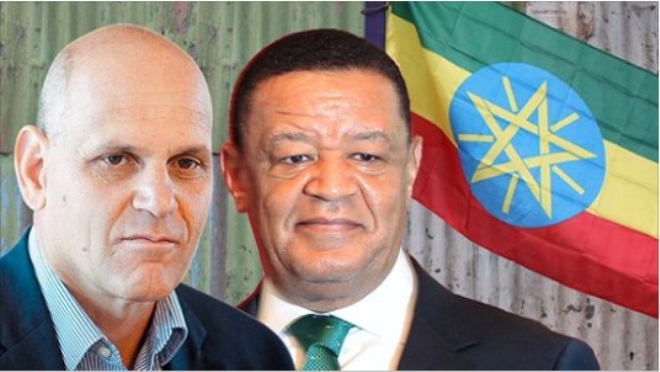

Israel-based defense outfit Elbit Systems Ltd. provided the Ethiopian government with spyware software that was used to track journalists and dissidents, according to a report published Tuesday by The Citizen Lab, a laboratory based at the Munk School of Global Affairs at the University of Toronto.

The report reveals a cyber campaign by Ethiopia targeting advocates of the Oromo ethnic group across 20 countries. The Ethiopian government was infecting the computers of its targets using a commercial spyware tool called PC Surveillance System (PSS), which is developed by a subsidiary of Elbit called Cyberbit Ltd.

The Oromo group represents around 35% of Ethiopia’s population, according to a 2007 census. In November 2015 protests sparked following a government plan to expand the country’s capital Addis Ababa into the Oromia region, causing the government to impose a state of emergency and leading to clashes resulting in hundreds of casualties.

Though the plan was scrapped, it reignited some of the underlying demographic issues in Ethiopia. In August, Ethiopian government lifted the state of emergency. As sporadic clashes continue it announced a ban on protest rallies earlier this month.

The Toronto researchers discovered a digital fingerprint known as a logfile, which allowed them to follow Ethiopia’s cyber campaign for more than a year. They have previously published reports in 2014 and 2015 about spyware attacks against Ethiopian journalists.

According to the report, this is the first time a spyware by Cyberbit is identified under such circumstances, but it’s not the first Israel-made spyware identified by Citizen Lab. Last year, it was researchers from this lab that uncovered a spyware made by another Israel-based cyber company, the NSO Group, which was used by a customer in the United Arab Emirates to target human rights activist Ahmed Mansoor. Earlier this year, the lab reported that the same spyware was used to target activists, journalists and political opposition in Mexico.

Established in 2015 as a wholly owned subsidiary of Israel-based Elbit Systems, a defense and homeland security manufacturer and contractor, Cyberbit now includes Elbit’s cyber intelligence and cybersecurity operations. The same year, Elbit acquired the intelligence division of Israel-based NICE Systems Ltd. for $158.9 million and merged it into Cyberbit.

After uncovering Cyberbit’s logfile, Citizen Labs were also able to track Cyberbit employees on their business trips, revealing a list of potential clients that includes militaries and totalitarian governments. Cyberbit appears to have demonstrated its PSS (PC Surveillance System) product to the Royal Thai Army, Uzbekistan’s National Security Service, Zambia’s Financial Intelligence Centre, and at the Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte’s palace. Cyberbit employees are also believed to have visited France, Vietnam, Kazakhstan, Rwanda, Serbia, and Nigeria for demos.

In response to a request for comment, a Cyberbit spokesperson said in an email: “Cyberbit is a defense company selling intelligence and cybersecurity products, adhering to the regulations and directives by the Israel’s Ministry of Defense, to Israeli legislation regulating defense exports, and to international agreements. Each marketing and sales process started by the company has been pre-vetted by the Israeli Defense Export Controls Agency, part of the Israeli Ministry of Defense. The company’s intelligence and cybersecurity products are intended for use by law enforcement organizations and state national security intelligence and defense agencies. Each deal is pre-vetted by the Israeli Ministry of Defense.”

The company’s comment further states: “intelligence and defense organizations buying the products are required to use them by law, and in accordance with the jurisdiction given to them by law. Cyberbit does not operate its products, and like other Israeli and non-Israeli defense companies, it is not fully aware of the way its products are being used in covert by nature activities by intelligence and defense agencies. In light of this, Cyberbit is committed to full confidentiality with regard to its clients and is not able to refer to any specific deal it has made, or to any specific client. The company’s products aid the national security of countries in which they are sold, and state agencies in such countries are required to operate these products within the law.”

Citizen Lab’s year-long investigation began with an email sent to Jawar Mohammed, the executive director of Minnesota -based Oromia Media Network (OMN), a satellite television channel that broadcasts into Ethiopia. Sent on October 4, the email impersonated a legitimate an Eritrean website and prompted its recipient to download an Adobe Flash Player update which, when downloaded, would have been bundled with spyware. Mr. Mohammed instead sent the email to Bill Marczak, senior research fellow and Citizen Lab and one of the authors of the report.

This was one of 11 such emails Mr. Mohammed received between May 30 and October 13, all carrying titles like “UN Report and Diaspora Reaction!” and “Egypt-Ethiopia new tension!”. In February 2017, four months after the last email, the Ethiopian government charged Mr. Mohammed, a U.S. resident, with terrorism.

The spyware used can track everything the computer does, take screenshots, copy files, identify passwords, and operate the microphone and camera to record Skype conversations or see what is happening around the computer, Mr. Marczak explained in an interview with Calcalist earlier this week.

Mr. Marczak and his fellow researchers started to investigate the malware and discovered a public logfile they could download off the server. “I think they had it there publicly for debugging or testing purposes,” Mr. Marczak said, but that meant they could see an open directory that listed all of the files on the site, including a frequently updated list of the IPs people who were being targeted. “That doesn’t give you the identity of the people targeted, but it allows you to see roughly the location.”

Since the researchers knew Mr. Mohammed was one of the targets, and they knew the areas being targeted, they asked Mr. Mohammed if he knew people in these cities who could also be targeted. They then cross-referenced their IP addresses to the logfile. “In a few cases,” Mr. Marczak said, “we found emails that were sent containing the spyware, where the operators forgot to put the addresses in BCC.”

The targets identified were mainly people of Oromo ethnicity or Oromo activists.

“I’m sure they’re doing other campaigns against other groups too,” Mr. Marczak said, “but since our window into the spyware started from the Oromo case, that was the one with the most visibility to us.”

Among the people targeted by the Ethiopian government who agreed to have their name revealed are Etana Dinka, a PhD student at the SOAS University of London, a frequent commenter on OMN; and Dr. Henok Gabisa, a visiting academic fellow at Washington and Lee University School of Law who is also the founder of the Association of Oromo Public Defenders, a public interest lawyer association.

Overall, the Citizen Lab identified 43 distinct infected devices across 20 countries. In five countries they found several infected devices—Eritrea (7), Canada (6), Germany (6), Australia (4), U.S. (4) and South Africa (2). In Belgium, Egypt, Ethiopia, U.K., India, Italy, Japan, Kenya, Norway, Qatar, Rwanda, South Sudan, Uganda and Yemen, one infected device was identified.

In March, the spyware operators tried to infect Mr. Marczak himself, with an email titled “Martin Plaut and Ethiopia’s politics of famine,” from an entity called Network Oromo Studies. Mr. Marczak, who was in the midst of reaching out to possible targets, recognized the sender’s email address as one used by the operators. He’s never become a target during an investigation before, he said during the interview. It’s funny, since “If you’re a smart operator you don’t want to target the researcher because that’s handing them your spyware on a silver platter.”

The logfile was also the key to identifying the Ethiopian government as the body behind the campaign, and Cyberbit as the company that provided the malware. The researchers had access to a year of operations, and the attackers logged on from three specific IP addresses. One was a satellite connection; one was a VPN service. The third, used for a very short time, was an Ethio Telecom address, a service provider owned by the Ethiopian government.

Combined with the “habitual misuse of spyware by the Ethiopian government against civil society targets,” the identity of the targets and the characteristics of the spyware campaign, Citizen Lab concludes that the government or its agencies appear to be behind it.

When the researchers analyzed the spyware itself, they revealed digital fingerprints and signatures from the file. They found a very similar sample from 2014 signed by C4 Security, a company acquired by Elbit in 2011 for $10.9 million. According to one employee’s LinkedIn page, C4 also developed a product called “PSS Surveillance System,” and PSS is also referenced on Elbit’s website as a product they provide, according to the report. They also found servers and IP addresses connected to Cyberbit that were related to the spyware.

Citizen Lab also identified possible clients of Cyberbit based on the activity of Cyberbit-linked IPs in various locations worldwide, perhaps related to sessions in which the software was demoed, though Mr. Marczak cautions that there could be other explanations for such activity.

Citizen Lab connected IPs linked to such sessions to IP addresses including The Royal Thai Army, Uzbekistan’s National Security Service, Zambia’s Financial Intelligence Centre, the Philippine President’s Malacañang Palace, and to the offices of a company called Kazimpex, said to be linked with the National Security Committee of the Republic of Kazakhstan (KNB), a Kazakh state intelligence agency.

The researchers also identified single-device, long-term infections in countries where Cyberbit has no known presence, including Iran, Canada, Finland, Indonesia, and Slovakia.

Mr. Marczak believes weak regulation on the sale of surveillance products leads to abuse of such tools. “The key point here is that there are governments and there are police agencies or intelligence agencies that are using products like this in a legitimate way. But there are also ones like Ethiopia or the UAE that are targeting human rights activists or a part of society,” said Mr. Marczak.

By

![]()