Kenya’s protracted election dispute has spawned secession calls from opposition supporters who say their vote has no influence on how East Africa’s biggest economy is governed.

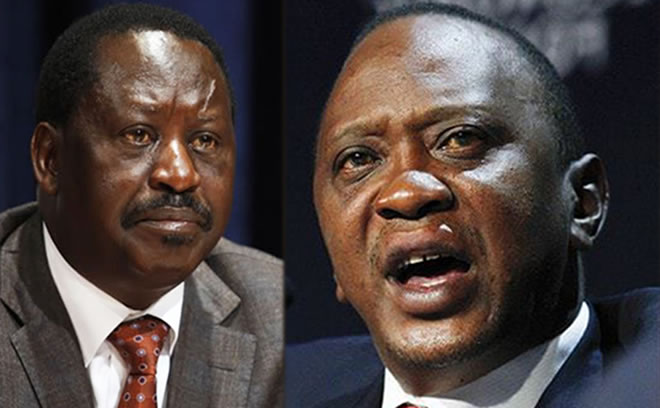

The increased agitation follows the declaration of President Uhuru Kenyatta as the winner of October’s election rerun that the main opposition alliance boycotted, alleging it wouldn’t be a fair vote. His victory in the poll, in which turnout was just 38.8 percent and clustered in central Kenya, may be encouraging secessionist ideas among those in the west of the country and on its eastern coastline.

While pro-secession sentiments were previously fueled by notions of “economic marginalization,” they’re “being deepened by what they perceive as electoral thefts,” said Abdullahi Boru Halakhe, an East Africa researcher at Amnesty International. “They feel they vote and their vote doesn’t count. Secession is now in the mainstream.”

The proposals mirror a wave of debate over self-determination that’s swept from Catalonia in Spain to Iraqi Kurdistan this year. Elsewhere in Africa, activists in southeastern Nigeria have stepped up a campaign for a Biafran state, half a century after an attempt sparked a civil war that claimed more than a million lives.

Four Presidents

Since Kenya’s independence from Britain in 1963, three of its four presidents including Kenyatta have been Kikuyu, the largest of its more than 40 ethnic groups and whose traditional homeland is in the central highlands. The other was Kalenjin, the fourth-biggest community and with origins in the center-west, as is current Deputy President William Ruto.

The second- and third-largest communities, the Luhya and Luo, have roots in western Kenya and opposition candidate Raila Odinga belongs to the latter. They’ve voiced frustration over their exclusion from high office, while regions far from the capital, Nairobi, have complained of underdevelopment. Although devolution was introduced in 2013 in an attempted compromise, Odinga’s fourth failed presidential bid has re-awakened notions of inequality.

“The marginalized communities and groups do not feel fully and equally Kenyan,” according to a bill submitted to electoral authorities by Peter Kaluma, a lawmaker for Homa Bay town in western Kenya. Seeking a constitutional amendment to allow the secession of 40 of the nation’s 47 counties, it calls for “the creation of a new state to give effect to the aspirations of the people of Kenya.”

Kenyans first voted this year in an Aug. 8 poll in which turnout was about 79 percent and that Kenyatta was initially declared to have won. Odinga alleged rigging and appealed to the Supreme Court, which on Sept. 1 annulled the result in a first for Africa.

Regional Hub

Although the ruling was hailed as marking institutional maturity, the uncertainty has threatened to undermine Kenya’s reputation as a top African investment destination and a regional hub for companies such as General Electric Co. and Coca-Cola Co. The opposition boycotted the Oct. 26 rerun while the court is considering two petitions to annul Kenyatta’s fresh win.

Kenya may be “torn apart” unless problems of marginalization are addressed, Odinga said last week in a speech at the Center for Strategic & International Studies in Washington.

“The depth of the crisis can be seen in the hitherto unheard of phenomenon of mainstream Kenyans feeling so deeply excluded that they are openly toying with the secessionist idea,” he said.

The Star, a Nairobi-based newspaper, illustrated a Nov. 10 opinion piece with a map showing the country split into a central republic and a breakaway “people’s republic” comprising the coastline and swathes of the south, west and northwest. The article called the secession proposal a “brilliant negotiation tactic for the present, but doomed to failure as practical policy for the long term.”

‘Political Concessions’

Odinga may be escalating the debate to win “political concessions” as the electoral dispute continues, according to Rashid Abdi, a project director at the International Crisis Group.

“This is a problem that has been there and the opposition has given it greater currency because of the elections dispute,” he said by phone from Nairobi.

“I don’t think the opposition’s endgame is the Balkanization of Kenya,” he said.

Kenya’s coastal region has started a “consultative process towards secession,” Hassan Ali Joho, Mombasa county governor, said Nov. 3. “It is no longer feasible for us as people to continue in a country that does not recognize our aspirations as legitimate.”

Mombasa hosts East Africa’s biggest port, the world’s largest tea auction and beaches that are a major attraction for foreign tourists. A 2012 secession campaign by the Mombasa Republican Council was quashed by the government, which arrested its leaders.

If groups wish for areas to secede they should follow constitutional provisions, otherwise they could be charged with treason, David Murathe, vice chairman of the ruling Jubilee Party, said by phone.

“They have to amend the constitution through a referendum,” he said. “They can go, good riddance.”

By Felix Njini