As in many other African nations, Somalia exists in a state of legal pluralism where customary law (Xeer), religious law (Sharia) and secular law operate. Among the three, Xeer is the dominant system that governs societal relations and serious crimes, due to a variety of historical and political reasons. Its persistence through years of civil war was primarily due to its core position underpinning the legitimacy of Somali traditional structures, especially in the provision of justice and arbitration, as first the Somali state and then society fractured. In this article, the experience of the Danish Demining Group (DDG) is highlighted to illustrate how traditional systems of customary law were reinvigorated to include women and young people, and formalised in written text to improve conflict resolution with a human rights approach.

The importance of Xeer in the Somali context was and is, for the most part, indisputable. Much like the clan system, it is an ever-present part of the Somali way of life. Throughout the 1990s civil war and its aftermath, traditional structures – Xeer and the elders who practise it – were a consistent resource for communal conflict resolution and, in a way, security. However, the process is not without its flaws. Historically, women and minority groups – such as the Bantu tribes and agrarian Somalis – suffered discrimination within these processes and were not permitted a voice. Moreover, Xeer legitimacy was also not without questioning. In some areas of southern Somalia, warlords and their military power superseded traditional respect for elders. In addition, Al-Shabaab controlled areas only followed by Sharia law.

Bearing this in mind, DDG’s initiative, Civic Engagement in Reconciliation and State Formation in Southern Somalia (CERSF), aimed to revitalise Xeer and Guurti,1 preserving its community aspect and strengthening its legitimacy at the local level. The approach was to build the capacity of elders to solve or mediate conflicts focused on root causes (rather than arbitrate high-value cases) in a way that was compatible with human rights standards and promoted the inclusion of women, youth and other underrepresented groups. This initiative is part of DDG’s armed violence reduction work, to reduce the impact of conflict and armed violence by mitigating the threats that small arms and light weapons pose to human security and development. This includes improving the relationship between community decision-making bodies, security providers and the community at large through facilitated dialogue and building conflict management and mediation capacity in key stakeholders.

Background

Somalia’s development of local security and governance structures over the past decade has been possible in large part due to the re-emergence of justice systems across the country. A mixture of modern, traditional and religious systems now provide more social order, less impunity and greater trust in the vision of a “Somali state”. These mainly community-based systems regulate a wide variety of affairs, from constitutional crises in regional political administrations to the enforcement of business contracts and the settlement of marital disputes. Although this trend has not provided for a full consolidation of rule of law by ending the use of arbitrary power, it has facilitated the development of Somalia’s growing economy, an increasingly active civil society, and the re-establishment of the country’s social fabric through local peacebuilding efforts.

In 1960, Somalia became an independent state from the United Kingdom and Italy.2 Even with a history of colonisation, the Somalis remained a fairly homogeneous nation in language, ethnicity, culture and religion, which is highly unusual for the African continent.3 For the first years of its independence, Somalia enjoyed relative internal peace, despite constant boundary disputes with neighbouring Djibouti, Ethiopia and Kenya. In 1969, following the assassination of President Abdirashid Ali Shermarke, Somali National Army General Mohamed Siad Barre seized power in a coup d’état. He proclaimed Somalia a socialist state, and had the military and financial backing of the then-Soviet Union. The subsequent freezing of aid by Western donors in 1988–1989 led to the rapid withering of a central government left virtually devoid of resources. The Barre regime ultimately failed to consolidate power effectively domestically, which led to a complete government breakdown in 1991.

The withdrawal of foreign peacekeeping troops during the 1990s brought new rounds of conflict between Somalia’s militia factions, which spread across southern Somalia. Clan-based factions began to split into competing subclan militias, and their leaders became increasingly entrenched in localised political and economic issues. Conflicts between the militia factions remained serious, claiming many lives, and continued to impede opportunities to build national unity.

According to Ken Menkhaus, the brutal civil war altered the fundamentally predatory relationship between many faction leaders, their militias and the communities that hosted them: “[A]s the symbiotic relationship between armed groups and villagers evolves, the line between extortion and taxation, between protection racket and police force is blurred, and a system of governance within anarchy is born.”4 The overlap between community interests and armed groups’ interests meant that popular pressures for social stabilisation began to influence and even circumscribe some armed groups’ activities. Efforts towards a locally driven process of re-establishing grassroots governance in Somalia began to materialise, and this is where DDG saw the opportunity to strengthen local conflict management mechanisms.

Strengthening Conflict Management within Xeer

DDG has had projects in Somali territory since 1999. The focus of the first interventions was the reduction in the impact of mines and explosive remnants of war (ERW). However, with time, DDG noted that to promote more peaceful, just and inclusive societies, there was a need to develop a comprehensive approach that would strengthen communities’ resilience and their capacity to prevent and address root causes of violent conflict. As such, the armed violence reduction team began conceptualising ways in which traditional structures and practices could incorporate human-rights approaches, which meant long-term programming focused on local ownership to see actual changes within traditional knowledge, attitudes and practices.

It was important to understand the social dynamics and power relations in Somalia, which are mostly based on the country’s clan system. In the words of Bernhard Helander, the clan structure forms “a completely encompassing social grid that organises every single individual from the time of their birth”.5 Genealogically, Somali society can be divided into four major clan families that comprise the vast majority of the country’s population: the Darod, Dir, Hawiye and Rahanweyn,6 as well as a nominal “fifth clan” of minority Arab and Bantu groups. Each clan comprises varying levels of subdivision that descend hierarchically from clan families to clans, subclans, sub-subclans, primary lineage groups and diya-paying groups.7 Diya is compensation (usually livestock) paid by a person who has injured or killed another person. Many times, it is referred to as blood money. A diya-paying group is made up of a group of men linked by lineage and a contractual agreement to support one another, mostly with regard to compensation for injuries and death against fellow members.

Clans and their subdivisions have traditionally been the primary means of social organisation for pastoralist and agro-pastoralist communities in Somalia, as well as the building blocks for intercommunity alliances and disputes. As neighbouring clans historically competed over scarce environmental resources – particularly land and water – a customary code of conduct, known as Xeer, was developed to settle disputes and maintain the social order. The sources of Xeer precede Islamic and colonial traditions, and are generally considered to be the agreements reached by elders of various clans who lived and migrated adjacent to one another, in an analogous way to court precedents. However, it is not a written legal code, but rather a tradition that has been passed down orally from one generation to the next.8

Due to its local nature, there are aspects of Xeer that are not universal. In fact, Xeer is divided into two categories: Xeer Guud and Xeer Gaar. Xeer Guud includes criminal and civil matters and is applicable to all clans, whereas Xeer Gaar is a decision only applied in its specific community. It is important to also clarify that even though Xeer Guud is universal in its application, the specific subsections and interpretations by the respective Guurti might change between communities.

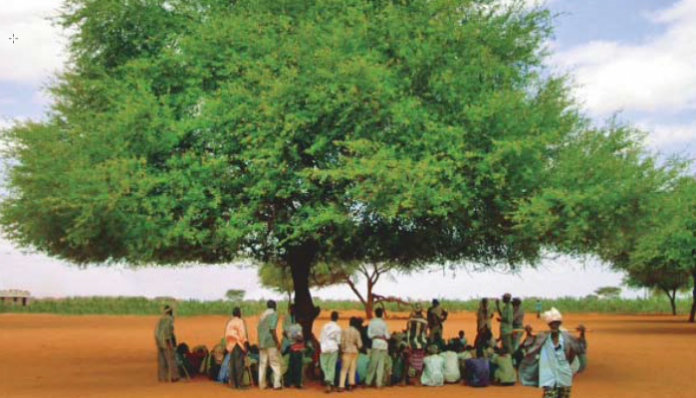

In practice, when two parties are in conflict, the Guurti of the two conflicting parties convene a shir beeleed (clan assembly) to discuss the issues at stake. The elders examine relevant precedents or relevant Xeer on the matter. If no relevant codes are found, the elders resort to Sharia for reference. If reference is obtained from Sharia, it then becomes part of the Xeer.9 It is important to highlight that this entire process is oral, so there are no written precedents or Xeer.

However, Xeer cannot be considered a strictly “rule-based” system. The political and military capabilities of a clan in relation to its rivals have always been important factors in reaching an enforceable consensus. This is the root of the unequal power relations within Guurti, and overall within Xeer. Women and minority clans have been historically and systematically excluded from the decision-making process, and mostly disenfranchised by it. This lack of representation and systematic discrimination was not without consequences. For example, the Rahaweyn, a marginalised group from the Shabelle Valley that comprise most of the foot soldiers of Al-Shabaab, were said to join Al-Shabaab explicitly because they refused to accept the unequal power relationships of Xeer and clan dynamics.10

Despite its unequal power dynamics, Xeer was – and still is – the most legitimate institution for conflict resolution in Somalia. Instead of forcing systems that would be foreign to Somali culture, DDG decided to explore the potential of Xeer as an alternative dispute resolution system that could use negotiation, mediation and arbitration to resolve disputes peacefully, and strengthen Guurti as a political space at the community level that could be influenced to be more inclusive.

This opportunity arose with the CERSF, whose aim was to contribute to the strategic objectives of peacebuilding and state-building by supporting effective civil society engagement. The project focused mainly on advancing inclusive political dialogue to clarify and settle relations between the federal government and existing and emerging administrations, and promoting peace processes of social reconciliation to rebuild trust among communities. Before the project implementation started, it was extremely important to build the internal capacity on Xeer and Guurti, and understand ways in which human rights principles and conflict management education could be built into those structures. The bottom-up approach used during the entire process was one of the key elements for its acceptance, but the project must still improve on its efforts to collaborate with the Office of Traditional Dispute Mechanisms under the Ministry of Justice.

During the project, traditional elders and communities engaged in dialogue about the importance of wider representation within Guurti to strengthen its legitimacy. The goal was to support communities to maintain the ethical aspects of Xeer, while moving away from its more outdated and oppressive practices. To do that, elders and community leaders of more diverse backgrounds (identified during previous projects) were trained in conflict analysis, prevention and management, and in peacebuilding. The communities were invited to be part of peace and justice dialogues, where they could discuss past grievances and ways in which the decisions could be fairer for all involved.

In parallel, processes of translating Xeer into a written conflict resolution code took place. Local committee members were brought together with a broader coalition of actors such as clan elders, civil society activists, youth and women’s groups to develop conflict prevention and response strategies, as well as to monitor the implementation of Xeer agreements. Local government, especially justice and security staff, were also part of the capacity-building processes to learn about conflict management and ways in which they could plan their service delivery as a tool to address conflict drivers. The key CERSF project achievements included the establishment of town-wide Xeer guidelines and Guurti formations in Kismayo, Baidoa, Jowhar and Mogadishu. Due to the success of the first round of activities, DDG was able to keep the initiatives going as part of other projects – and was able to support the coding of Xeer and the inclusive version of Guurti in the Harfo, Dangorayo and Iskushuban areas in Puntland; Xudur in the Bakool region, Warsheikh in the Middle Shabelle region; and Luuq and Beled Hawa in Gedo.

It is important to highlight that local ownership takes time, as does changing unfair and unequal power relations in societies. DDG has managed to make some progress with this process at the local level because the organisation has worked at the community level for 17 years. There is a level of acceptance and legitimacy needed to build up processes that must not be ignored at the expense of quick results. Somali communities, like most communities, reward consistency. In addition, with an ever-changing political scenario, the presence of armed groups, recurring humanitarian crises, long-term changes in governance and peace will not necessarily figure into political priorities or funding cycles. This underlines the importance for consistency and long-term community programmes.

Essentially, DDG’s initiative aimed to revitalise Xeer and Guurti, preserving its community aspect and strengthening its legitimacy at the local level. It did this by building the capacity of the elders to solve or mediate conflicts focused on root causes, in a way that is compatible with human rights standards, while promoting the inclusion of women, youth and other under-represented groups. It is impossible to state at this point whether this intervention will have a long-term effect on traditional justice in Somalia, due to its ever-evolving nature, but it is possible to say that by incorporating human rights principles, inclusive practices and effective conflict management mechanisms into traditional justice, communities are now more willing and able to use the aspects of Xeer and Guurti that contribute to a more peaceful and just Somalia.

Conclusion

Somalis still largely rely on traditional justice systems, especially at the local level, due to the overall lack of trust and perceived ineffectiveness of the secular justice system. In this sense, the Somali experience is not unique: international research11 and experience shows that communities that are excluded or lack access to effective state services usually rely on their traditional governance mechanisms or create new, local ones.

DDG saw this as an opportunity to strengthen communities’ ability to prevent and manage conflict, while also advocating for more inclusive local governance structures. This process was not without its challenges, especially regarding the long-term inclusion of women, youth and minority groups. However, the progress made and the achievements to date show that it is possible for traditional justice mechanisms to be avenues for reconciliation and localised peace. Moreover, it showed that traditional mechanisms and human rights principles are not inherently incompatible.

Endnotes

- Guurti generally refers to a political assembly of elders, such as in Somaliland. In DDG intervention, it refers to the traditional body of elders involved in conflict resolution. Different communities provide a different name for these bodies of elders – they could be called Odayaal, Malaaqs or Nabaddono. Guurti has now been adopted as a general name, and it provides more legitimacy.

- Le Sage, Andre (2005) Stateless Justice in Somalia: Formal & Informal Rules of law Initiatives. Geneva: Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, pp. 18–19.

- Somalis are almost entirely Muslim, from the Shafi’i school of Sunni Islam. It is popularly believed by Somalis that their ancestors descended from the household of the prophet Mohamed, so that all Somalis belong to the Hashimite stock of the Qurayshi clan. However, the precise history of Islam’s penetration into present-day Somalia is not known. Arab traders had already established a presence along the Somali coast in pre-Islamic times. But the diffusion of Islam is usually dated to successive waves of Arab emigration and conquest between the 7th and 13th centuries, originating from Arabia, Persia, Yemen and Oman.

- Menkhaus, Ken (1998) Somalia: The Political Order of a Stateless Society. Current History, (97), p. 222.

- Helander, Bernard (1997) Is There a Civil Society in Somalia? Nairobi: UNDOS.

- Rahanweyn is a collective name that is actually divided into two main groups, known as Digil and Mirifle.

- Gundel, Joakim (2009) Clans in Somalia. Vienna: Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation.

- Van Nooten, M. (2005) The Law of the Somalis: A Stable Foundation for Economic Development in the Horn of Africa. The Red Sea Press Inc.

- Abdile, Mahdi (2012) Customary Dispute Resolution in Somalia. African Conflict and Peacebuilding Review, (2)1, pp. 87–110.

- Canada: Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (2015) ‘Somalia: The Biyomal Clan, Including Work, History, Religious Affiliation, Location within the Country, Particularly Nus Dunya; the Rahanweyn Clan, Including Location in the Country; Treatment of the Biyomal Clan by the Rahanwen Clan (2013-September 2015)’, available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/56f399224.html [Accessed 6 August 2017].

- Rose, Cecily and Ssekandi, Francis M (2007) The Pursuit of Transitional Justice and African Traditional Values: a Clash of Civilizations – The Case of Uganda. Sur, Rev. int. direitos humanos., (4)7, pp. 100–12. Tshehla, Boyane (2005) Traditional Justice in Practice: a Limpopo Case Study. Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies, pp. 31–41.

BY NATASHA LEITE