A crack more than 120 miles long had developed over several years in a floating ice shelf called Larsen C, and scientists who have been monitoring it confirmed on Wednesday that the huge iceberg had finally broken free.

How the crack grew

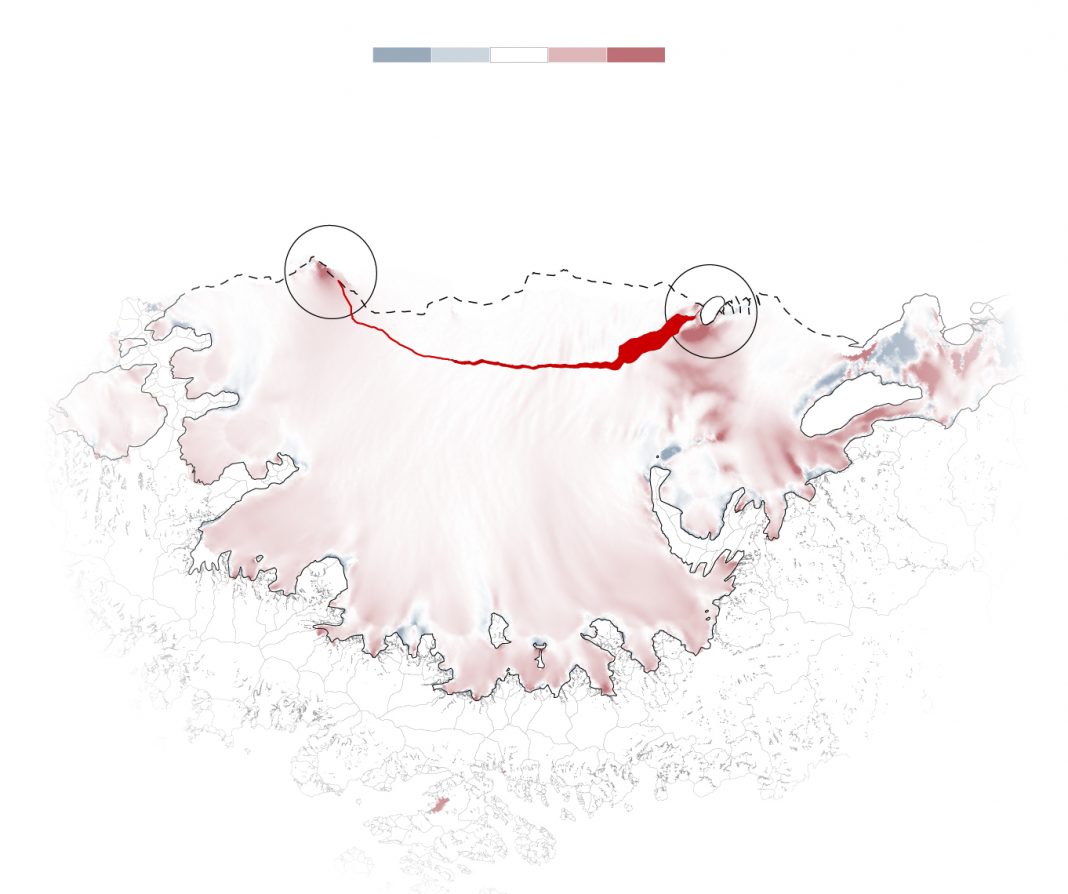

After accelerating across the Antarctic Peninsula, the direction of the crack sharply turned 90º in May.

If Larsen C’s shelf front retreats past this line, called the compressive arch, the shelf is likely to collapse.

There is no scientific consensus over whether global warming is to blame. But the landscape of the Antarctic Peninsula has been fundamentally changed, according to Project Midas, a research team from Swansea University and Aberystwyth University in Britain that had been monitoring the rift since 2014.

“The remaining shelf will be at its smallest ever known size,” said Adrian Luckman, a lead researcher for Project Midas. “This is a big change. Maps will need to be redrawn.”

Larsen C, like two smaller ice shelves that collapsed before it, was holding back relatively little land ice, and it is not expected to contribute much to the rise of the sea. But in other parts of Antarctica, similar shelves are holding back enormous amounts of ice, and scientists fear that their future collapse could dump enough ice into the ocean to raise the sea level by many feet. How fast this could happen is unclear.

In the late 20th century, the Antarctic Peninsula, which juts out from the main body of Antarctica and points toward South America, was one of the fastest-warming places in the world. That warming had slowed or perhaps reversed slightly in the 21st century, but scientists believe the ice is still catching up to the higher temperatures.

Some climate scientists believe the warming in the region was at least in part a consequence of human-caused climate change, while others have disputed that, seeing a large role for natural variability — and noting that icebergs have been breaking away from ice shelves for many millions of years. But the two camps agree that the breakup of ice shelves in the peninsula region may be a preview of what is in store for the main part of Antarctica as the world continues heating up as a result of human activity.

“While it might not be caused by global warming, it’s at least a natural laboratory to study how breakups will occur at other ice shelves to improve the theoretical basis for our projections of future sea level rise,” said Thomas P. Wagner, who leads NASA’s efforts to study the polar regions.

The time-lapse image below shows the rift gradually widening from late 2014 to January of this year.

Rift extent

Area of detail

In frigid regions, ice shelves form as the long rivers of ice called glaciers flow from land into the sea. The result is a bit like a clog in a drain pipe, slowing the flow of the glaciers feeding them. When an ice shelf collapses, the glaciers behind it can accelerate, as though the drain pipe had suddenly cleared.

At the remaining part of Larsen C, the edge is now much closer to a line that scientists call the compressive arch, which is critical for structural support. If the front retreats past that line, the northernmost part of the shelf could collapse within months.

“At that point in time, the glaciers will react,” said Eric Rignot, a climate scientist at the University of California, Irvine, who has done extensive research on polar ice. “If the ice shelf breaks apart, it will remove a buttressing force on the glaciers that flow into it. The glaciers will feel less resistance to flow, effectively removing a cork in front of them.”

Scientists also fear that two

crucial anchor points will be lost.

According to Dr. Rignot, the stability of the whole ice shelf is threatened, as the shelf front thins.

“You have these two anchors on the side of Larsen C that play a critical role in holding the ice shelf where it is,” he said. “If the shelf is getting thinner, it will be more breakable, and it will lose contact with the ice rises.”

If the shelf front disconnects from the ice rises, a rapid retreat will be triggered.

Ice rises are islands that are overridden by the ice shelf, allowing them to shoulder more of the weight of the shelf. Scientists have yet to determine the extent of thinning around the Bawden and Gipps ice rises, though Dr. Rignot noted that the Bawden ice rise was more vulnerable.

“We’re not even sure how it’s hanging on there,” he said. “But if you take away Bawden, the whole shelf will feel it.”

The Antarctic Peninsula may

be a canary in a coal mine.

The collapse of the peninsula’s ice shelves can be interpreted as fulfilling a prophecy made in 1978 by a renowned geologist named John H. Mercer of Ohio State University. In a classic paper, Dr. Mercer warned that the western part of Antarctica was so vulnerable to human-induced climate warming as to pose a “threat of disaster” from rising seas.

He said that humanity would know the calamity had begun when ice shelves started breaking up along the peninsula, with the breakups moving progressively southward.

The Larsen A ice shelf broke up over several years starting in 1995; the Larsen B underwent a dramatic collapse in 2002; and now, scientists fear, the calving of the giant iceberg could be the first stage in the breakup of Larsen C.

“As climate warming progresses farther south,” Dr. Rignot said, “it will affect larger and larger ice shelves, holding back bigger and bigger glaciers, so that their collapse will contribute more to sea-level rise.”

For more Times reporting on Antarctica, read the Antarctic Dispatches or watch four virtual-reality films in The Antarctica Series.