EU policy has stagnated while illegal migrants routes proliferate.

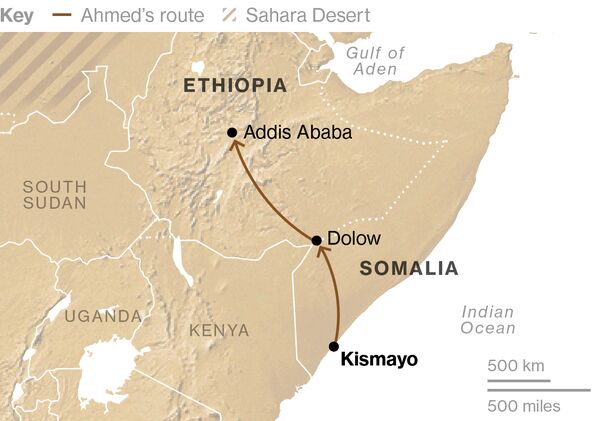

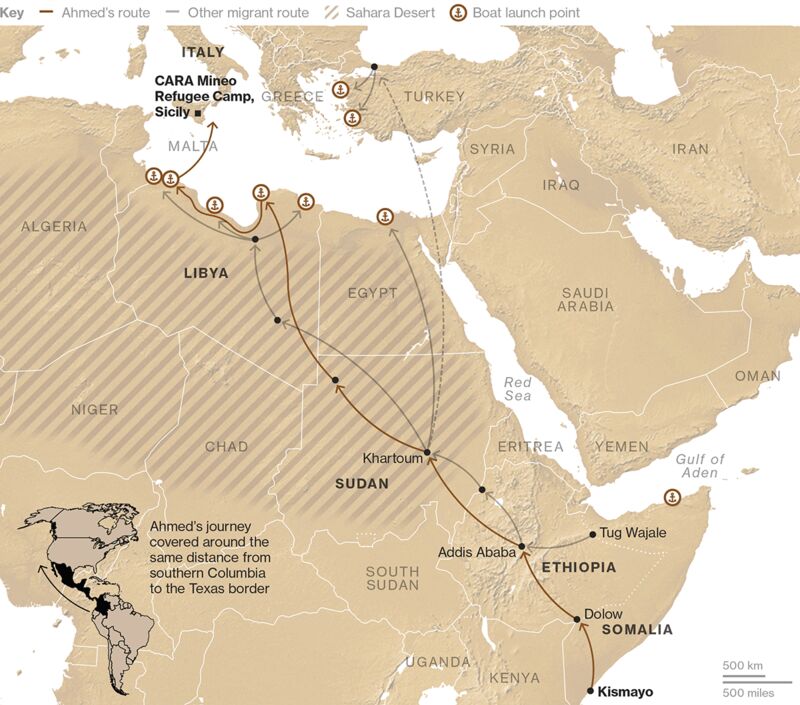

Ahmed was 23 when he left his village near Kismayo, on the southern coast of Somalia, because of a grinding lack of work. He travelled for 18 days across the dry Somali scrub, swaying on top of long-distance trucks, until he reached the town of Dolow, just south of the Ethiopian border. Locals sneaked him past border guards, by night, across the Jubba River. These Somali passeurs—the equivalents of “coyotes” who move immigrants across the U.S.-Mexican border—were the first people he met in a wide network of smugglers, facilitators, and violent extortionists who work the migrant trail from the Horn of Africa to Europe.

On the Ethiopian side, Ahmed stowed away on a grocery truck leaving for Addis Ababa, more than 600 miles northwest. “It is normal,” he said. “You will be stopped at a checkpoint, where you will be questioned. But the police let the Somalis pass because they know that Somalis have fled because of difficulties and insecurity.”

By this point, his passeurs, including the man who transported him to Addis Ababa, hadn’t charged him a thing. “He tell me I can pay later.”

Somalia has lacked a functioning central government since 1991, when the dictator Siad Barre fell, and a desultory civil war has thumped along clan boundaries in the dry desert bush ever since. Whole regions of the country belong to clan militias or al-Shabaab, the al-Qaeda-linked Salafist group, and there are few jobs. Many Somalis in the past few years have migrated toward Europe, like other African refugees, along now-established smuggling routes that are more dangerous than they might seem from the vantage of a Somali village.

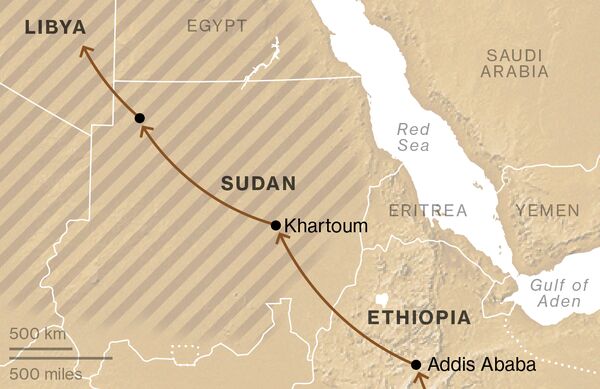

The past few years of chaos in Libya have opened a path through that country to Europe, and Ahmed’s journey was typical. He was headed for Italy through the central Mediterranean route, which can start deep within Africa. Smugglers brought him to a town near Addis and installed him at a restaurant, where he washed dishes for nine months, earning $20 a month. Work for little or no pay is common along the migrant trail; many smugglers look at migrants as a source of cheap labor. When the time came, he moved on. Ahmed couldn’t say whether all the people he met in Ethiopia belonged to the same network, but he was in the hands of one smuggler or another from the Somali border all the way to Libya.

From Addis, he took an 11-day car journey across the Sahara to northern Sudan. “We left in the night,” he said. “You never know where you are going and where you are. That is how my journey started. It took us 11 days to cross the desert.” He arrived at a large tent between two mountains near the Libyan border, full of migrants living in squalor. Now he learned the cost of his passage. “Some people, they come from Sudan, and they have to pay $2,000,” said Ahmed. “But if it’s all the way from Somalia to Libya, then you may pay $4,000 or $5,000.” Ahmed didn’t have $4,000 or $5,000. So the traffickers held him hostage in the tent, along with many migrants who couldn’t pay. They were fed “only pasta, cooked in not-good water. And a bottle of water every day, mixed with fuel, so we don’t drink it so fast. We were so thirsty, we had no choice.”

The traffickers made violent threats. “They would say, ‘You have one month to pay, otherwise we will start breaking your bones.’” Ahmed made a hacking gesture against his own arm. A large-bellied, 27-year-old man with round shoulders and lively eyes, Ahmed spoke to me last May at the “CARA Mineo” refugee camp in Sicily.

“Some of the people would try to escape into the mountains,” he said. “And some of these smugglers, when they catch you, they bring you in front of the others and shoot you in the head.”

I asked him whether he saw people get shot. “Yeah,” he responded.

How many?

“There was eight.”

How did he find the money to leave?

“Me, I didn’t pay anything. I had no family to call. I had no one back in Somalia except my mother. I knew they would break my bones, so I ran from the tent. At midnight.” With 15 other men he escaped “maybe 150 kilometers” into Libya. “We had no water, no food. It was hot.”

He’d made it to Libya, but it would be almost two more years before he could board a wobbling boat and risk drowning on the Mediterranean.

Ahmed belongs to the ongoing Great Migration, a now-seasonal swell of emigrants who try to cross the Mediterranean Sea from Africa to Europe during the warmer months of the year. It started in earnest in 2012, as Syria began to implode. The previous year’s Arab Spring revolts, which brought civil war to North Africa and the Middle East, created refugees who lit up African migrant networks that had existed for years like flickering underground circuits.

Somali migrants represent a small but significant fraction of the people who head for the central Mediterranean now—about eight percent in 2015, or 12,000 people — though numbers spiked in 2016 because of improved smuggling routes. One reason Somalis started to move along such a long and treacherous path is that a more traditional route (to the Middle East) has dried up. Somalis used to travel straight north, across the Gulf of Aden, in crowded fishing boats. They looked for jobs in Yemen or moved on to Saudi Arabia. But the Saudis cracked down on immigration in 2013, and in 2015 the civil war in Yemen grew so brutal that the net flow of people has shifted southward, from Yemen back to Somalia.

Smugglers help in both directions. Some, on the Yemen route, are also pirates. A World Bank report published in 2013 tells the story of a smuggling boat that moved Somali migrants north to Yemen from Puntland, a Somali state notorious for piracy. The smugglers rode “across the Gulf of Aden in a whaler-type vessel that was towing a second empty skiff,” according to the report. On the way back to Puntland they stumbled on a Singapore-flagged chemical tanker, the MV Pramoni, trundling eastbound through the Gulf of Aden. The smugglers “made an opportunistic and successful attack” using the skiff. They turned pirate, in other words, and forced the Pramoni to sail around the Horn of Africa to Eyl, a pirate nest on Somalia’s eastern coast. The vessel and its captive crew waited two months for a ransom to arrive. Indian crew released from pirate captivity by German EU Naval Force frigate FGS Berlin.

Indian crew released from pirate captivity by German EU Naval Force frigate FGS Berlin.

Pirates on East African migrant routes have, so far, not come to the world’s attention, but their skiffs have lately gone quiet on the waters off Somalia. One reason is the presence of Western warships, including the European Union Naval Force mission, code-named Eunavfor Atalanta, which keeps the peace in the absence of a Somali navy. “If the pirate financiers thought for a moment that they could come out and catch a supertanker and get $12 million, rest assured they would be out there,” said Commander Jacqueline Sheriff, a British spokeswoman for Atalanta.

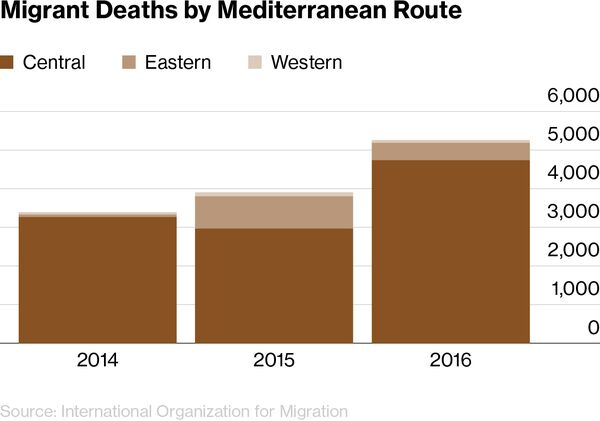

Eunavfor is also busy on the Mediterranean, rescuing migrants who have traveled through Libya. A desperate European Union deal with Turkey in March 2016 drastically reduced the number of migrants crossing the eastern Mediterranean, from Turkey to Greece. But dangerous boat crossings in the central Mediterranean, from Libya, are as frequent as ever, and 2016 became the deadliest year on record. An estimated 4,576 people died on the central-Mediterranean route in 2016, according to the International Organization for Migration, compared with 2,869 in 2015.

The leaders of individual member states have failed to agree on a coherent response to the flood of asylum seekers. Migrants put themselves in the hands of dangerous traffickers because they have no legal path toward European asylum from abroad, said Florian Westphal, a German spokesman for Médecins Sans Frontières, which runs rescue ships on the Mediterranean. “What we’re calling for is making it possible for people to seek and obtain protection in Europe through legal means … that do not oblige people to spend, very often, their life savings, or to risk their lives on a shoddy dinghy crossing the Mediterranean,” he said.

A European Commission proposal to control immigration with a bloc-wide resettlement plan has been presented in Brussels but tabled by EU member states, which can’t agree on terms—in particular on how to share the refugee burden.

The navies’ own humanitarian policy, in the meantime, is a shambles. Eunavfor has a mandate on the Mediterranean to “disrupt the business model of human smuggling and trafficking networks,” but in the current phase of the mission, warships can’t chase boats inside Libyan waters. So smugglers keep close to Libya to avoid trouble, and the navies do little but wait for rickety wooden fishing boats or rubber dinghies to float past Libya’s 12-mile territorial limit. The Libyan smugglers, in other words, use the rescue ships to promote their business model. A February 2016 report by Sahan Research, a Nairobi-based think tank, on East African smuggling argues that smugglers deliberately cause a “safety of life at sea” crisis, which obliges all ships to rescue migrants in danger. Officers on one German frigate charged with rescuing migrants, the Frankfurt am Main, quietly agree that the rescues are a “pull factor” for some migrants. But it’s better than letting them drown.

So the smuggling business has boomed, driving profit to a collection of affiliated criminal networks in sub-Saharan Africa that feed migrants to separate networks in Libya. If the EU were to prevent deaths on the Mediterranean without creating legal means for migrants to arrive, it would need to address these networks. But it’s done a poor job of understanding them, so far. “The EU’s policy to suppress and unravel migrant networks hasn’t worked, in part because they’re looking at it through a very law-enforcement and prosecutorial lens,” said Peter Tinti, a research fellow at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. “But these networks are incredibly fluid.” Some are centralized and well-organized, while others are casual. “We’re seeing a host of opportunists coming in to facilitate these migrant flows,” Tinti says. “And that’s much harder to combat.”

The EU recently agreed to pay $200 million to the Western-backed government in Libya to suppress the smuggling. But since a civil war has left the nation crippled, with two rival governments, the new deal’s potential may be limited. Eunavfor has started to train Libyan forces to slow the smugglers, but deeper inland, beyond Libya, feeder networks from East Africa have grown brutal and strong. There’s growing evidence that former Somali pirates work among them as foot soldiers, even financiers. Some of the pirates Eunavfor has frustrated off the Somali coast, in other words, are now helping move migrants toward Europe.

Young Somalis have a phrase, “going on tahriib,” for migration toward Europe, using an Arabic word for “illegal activity.” One common racket for Somalis on tahriib is a “leave now–pay later” scheme that entices young men to travel before they have money to pay, said Peter Tinti of the Global Initiative. “A lot of times, the people who use these schemes think they’re gonna pay once they have a job, or think that employment’s arranged on the other end. And it rarely is.”

The financiers in such a scheme will keep track of each migrant, said Dino Mahtani, a British UN investigator and an author of the Sahan Research report on East African smuggling. “The money people are aware of the individuals,” he said. “Even if a guy is passed along from one transporter to the next in Ethiopia, and he turns up in Sudan, and he’s told to go and find a relative, or he’s given the contact of somebody who says he can get him on—that contact will know how far he’s already traveled. And so, charges him accordingly.”

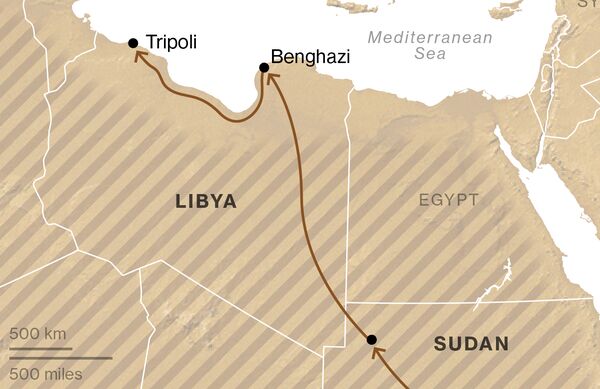

Ahmed was unaware of the financiers in charge of his path to Europe, but he broke out of his leave now–pay later network when he ran from his tent-prison in Sudan. Three of the men he escaped with died of thirst. The 13 others found their way to a Libyan desert town. “We stayed in a mosque,” said Ahmed, “and the people there gave us food and water.” They made it as far as Benghazi, on the coast, before an armed stranger captured Ahmed and one fellow migrant and ordered them to come home with him. “In the day he forced us to build his house, and in the night he handcuffed and blindfolded us,” Ahmed said. “He used to wake us up at 5 a.m. every morning to build his house until sunset.”

Human rights workers insist on a legal distinction between “trafficking” and “smuggling”: A smuggled person pays for passage, even if his smugglers are cruel; a trafficked person is held or used unwillingly. But the roles can blur. Ahmed had started on tahriib as a willing, smuggled emigrant at the Dolow crossing, in Ethiopia, and then was trafficked and abused.

Ahmed lived like a slave in Benghazi for a year. He escaped bondage there only because of the civil war. His Libyan masters wanted him to take a gun and defend the city, Ahmed said, but he refused: “When they left for the fight, I ran and escaped.” He made his way toward Tripoli and spent a further six months in the coastal metropolis, doing construction work for a man who promised to put him on a boat. “I would break stones, plant trees, build houses, and water the plants,” he said.

At last, one night in the spring of 2015, some men moved him to a rubber boat on the beach. With a hundred other people, he moved out onto the darkened Mediterranean. “We were on the water for 16 hours,” he said. One migrant carried a satellite phone and called an Italian number when the boat started to leak. “Then we were rescued by the Italian Coast Guard,” said Ahmed.

The rescue ships on the Mediterranean—the U.S. Coast Guard, NGO vessels, Eunavfor frigates —try to give some comfort to the people they scoop from the sea. They offer thin, warm stew and a quick medical checkup before delivering them to an Italian port. Ahmed arrived in Sicily in about March 2015. He’s still there, at the CARA Mineo refugee camp, waiting for European asylum.

The camp is a former U.S. military base, built among farms and citrus groves at the foot of a hill town in eastern Sicily. Up to 3,000 migrants, largely African and central Asian, live in suburban-style row houses behind a chain-link fence. This odd village has high-speed internet and satellite TV, a glum cafeteria, a makeshift church and mosque, and short asphalt streets with such names as Constitution Avenue and Decatur Drive. One Somali who works there as a translator and cultural mediator was a migrant himself: He left Somalia in 2007 along the same East African trail. I’ll call him Raheem. He’s a quiet young man about 30 years old, with a high voice. Through his job, he has heard a vast number of stories, and he said the changes since he made his journey have been stark. There’s more competition, more violence, and more money involved. “When I came to Italy nine years ago, everything was easy. There were not these traffickers,” he said with a look of distaste. “It was small before. The smugglers used to be gentle. There wasn’t all this chaos. … Now there are people beating you.”

A year ago, he started hearing stories of Somali “travel agents” offering passage to Europe to vulnerable or desperate Somalis. “They know the way. They can describe it,” said Raheem. These travel agents belong to a loose international network, he said. They offer leave-now-pay-later schemes to would-be migrants, and they can call connections as far off as Libya to announce: ”’We are going to send you these people.”

The most sophisticated feeder network from East Africa to Libya is Eritrean, with Somali and Ethiopian networks growing like vines behind it, according to the Sahan Research report. The report names a Somali living in Khartoum, Ali Hashi, as the person controlling most financial transactions for Somali migrants moving through Ethiopia toward Libya. He runs a “hawala” network, a Muslim money-transfer business. Hawala is used for a number of purposes that aren’t criminal, but experts suspect that they can also fund smuggling networks. “Money to secure the transport of passengers through Ethiopia and into Sudan is handled by hawala agents controlled in large part by a Khartoum-based Somali known as ‘Ali Hashi,’” says the report. Ali Hashi receives money in Khartoum and distributes it to smugglers at a border town in Somalia, “where the money is cashed out to finance the transportation network that feeds across Ethiopia into Sudan.”

The hawala system is less expensive than Western Union, farther reaching, and often untraceable. It lies outside the international banking system. Ali Hashi is the half-brother of another well-known hawala boss, Abdulkadir Hashi, who, according to the report, ran a network called Qaran Express during the heyday of Somali piracy. The brothers have the family name Jumaale, Dino Mahtani confirms. A UN report cites an example of “Qaran money” being used to pay a smuggler as early as 2009. “If you trace back to the start of [Qaran] in the mid-2000s, it was a small firm,” said Alasdair Walton, who follows criminal networks in Somalia and Libya for Hermes Associates, a consultancy in London, “yet by the time it ‘collapsed’ and became Horn Express, it was the second-largest hawala firm to Dahabshiil, with the growth coinciding with the increased cash flows linked to the rise of piracy.”

Ali Hashi’s hawala network might be a descendent of Qaran Express, said Walton, but it seems to have no official name. Every Somali I met in Sicily had crossed into Ethiopia at Dolow, in the south, and moved on to Khartoum. The Sahan report focuses on Ali Hashi’s relationship with a border crossing at Tug Wajaale, far to the north of Dolow. Mahtani said a single financier might nevertheless handle more than one crossing. “Khartoum is a chokepoint for everyone who’s gone through Ethiopia,” he said, “so Ali Hashi may well be connected to a much wider network.”

Stories of kidnapping and captivity on the African migrant trail have a personal angle for me. A pirate gang took me hostage near Galkacyo, in central Somalia, in early 2012. Ahmed’s stories of blindfolds, men with rifles, and pasta cooked with nasty water are familiar. I spent two and a half years in Somalia under similar conditions, and when I returned home to Europe the human crisis on the East African routes, in particular, started to ring weird bells in my head. Pirates had kept me alive on mango juice and sweet vanilla cookies called biskit, for example. A 2015 story from the Independent in London discussed a teenager named Ismail who migrated from Somalia using the same route as Ahmed: “The teenager was kidnapped, beaten and ransomed.” In Sudan, the boy had nothing to eat or drink except “biscuits and mango juice.”

Kidnapping and human trafficking have a lot in common: Organized criminal gangs in East Africa dominate both. It’s easy and often logical for the financiers and foot soldiers in one industry to cross over to another. During my last several months as a hostage, I lived in a large and filthy concrete house belonging to a boss who went by “Abdi Yare.” He died in a shootout over my ransom in September 2014, but during the height of the Somali pirate era he invested in a number of hijacked ships, including the SL Irene, a Greek supertanker. Pirates hijacked the Irene in February 2011 and anchored it off the central Somali coast. According to Rudy Atallah, CEO of Virginia-based security consultancy White Mountain Research, One Somali co-investor in the hijacking was Ali Hashi Jumaale, the migrant-smuggling financier in Khartoum.

“Ali Hashi financed the SL Irene,” Atallah said. “He operated in the Hobyo area and had close ties with Jama Horor on the hijacking of the Irene.” Jama Horor is a convicted Somali pirate now doing time in the United States, better known as Jama Idle Ibrahim.

Atallah retired from the U.S. Air Force as a lieutenant colonel; he worked on the Maersk Alabama hostage case and, briefly, on mine. He’s been known to run a reliable network of Somali informants. While pirates aimed their guns at Captain Richard Phillips on the Maersk Alabama’s lifeboat, Atallah gathered their names, and the U.S. navy broadcast a message from the pirates’ clan elders over a sound system. The idea was to encourage the four Somalis to give up before SEAL snipers took their lethal shots. “Abdiwali Muse, the one guy who turned himself in, that was because of me,” said Atallah.

No one at Eunavfor seems to have made a connection between pirate financiers in Somalia and kingpins on the East African trail—at least at the lower levels. No one aboard the Frankfurt, no one at Eunavfor’s Atalanta mission headquarters in the U.K., and no one at Eunavfor offices in Rome or Brussels even seems aware of references in U.N. reports to a crossover between the two industries, let alone the identity of Somalis helping to move migrants from East Africa toward Europe.

“It has not come to my attention that the pirates’ business model has been shifted from Somalia to Libya,” said Captain Andreas Schmekel, who was in charge of the Frankfurtwhile it rescued people from the Mediterranean in mid-2015. “Unfortunately, we do not hold such information,” said Commander Sheriff at Atalanta headquarters in Britain, when asked about Ali Hashi. Spokespeople at Eunavfor headquarters in Rome and at EU offices in Brussels wouldn’t return several e-mails and phone calls. Glen Forbes, who runs a maritime risk-advisory firm called Oceanus Live in Great Britain, said the European navies must be aware of crossover between Somali pirates and Somali migrant smugglers, at least in the Gulf of Aden, “but are keeping it below the radar, as it’s not part of their mandate.”

East Africans who want European asylum do business with far worse people than former pirates. One Somali at CARA Mineo was a smiling young woman named Saynab, with a plump face and a soft voice, who wore a white flowered headscarf. Last year, she crossed into Ethiopia and traveled all the way to Bahir Dar, an ancient city on the edge of Lake Tana, between Addis Ababa and the Sudanese border. She worked in Bahir Dar for two months, cleaning house and washing clothes for an Ethiopian man, who finally moved her to the edge of Sudan. She was held captive there for three months by a “friend” of the Ethiopian man’s, who demanded payment. When she couldn’t pay, “some guys come to the house,” she said, “and they used me to get money for my body. For eight months.” They allowed her to move on and board a rubber boat only after she got pregnant.

Since 2015, the naval group has promised that a new and tougher phase of its counter-smuggling operation would start as soon one rival government or another in Libya asks for military help (or as soon as the UN declares Libya a failed state, subject to intervention). Then warships, in theory, can move close to shore and safely turn back boats. “They’re waiting for the invitation—‘Oh, you can come into Libyan waters to blockade Sirte,’” said Jason Pack, from Libya-Analysis.com, referring to one of Libya’s port cities. But the Libyan leadership is fractured by civil war, and “they don’t want to seem reliant on foreigners” to solve their problems, according to Pack. Last June, Eunavfor extended the rescue phase of its mission for an additional year, effectively stalling plans to intervene. “It’s very doable,” Pack said of the intervention idea, “but it’s not a complete solution.”

A complete humanitarian solution would mean addressing the reasons people pick up and leave their homes. But it would also mean letting people in crisis-hit parts of the world apply for asylum from abroad, without handing themselves over to traffickers. The United States has used a largely successful version of this policy, which President Donald Trump wants to dismantle. After the Vietnam War, the U.N. created a longstanding Orderly Departure Program, which let refugees from Vietnam apply for asylum in the U.S. and other Western countries after 1980. This program ended the “boat people” crisis of the 1970s, and the U.S. government has used modified versions of the policy ever since to help refugees from certain crisis zones, including Haiti, Somalia, and Syria.

The UN’s High Commission for Refugees still allows long-distance resettlement from its far-flung camps in certain narrow cases, including severe illness, according to Joseph Janning, head of the Berlin office of the European Council on Foreign Relations. “The UN selects the people, and then it goes absolutely without trafficking. There is no Mafia, no criminal organization that can have any business” in moving people to the host countries, he said. “I think that is a very good model. But it will work for only a limited number of people. … Once you are deciding who will come through that resettlement program, the numbers will necessarily be lower.”

Ahmed, after more than four years of struggle, now has asylum paperwork to stay. (“I will work in Italy,” he said.) Under a resettlement scheme, he could have applied for asylum from home and awaited his papers in Somalia. Fewer migrants would be accepted under such a scheme; but successful applicants could fly to Europe without spending years as fugitives or slaves, as Ahmed did, and without risking their lives on the Mediterranean.

It’s an imperfect solution, but resettlement would have the advantage of both controlling mass migration to Europe and facing up to a powerful market force. “Any solution is going to involve reducing demand for smuggler services,” said Tinti. “Smugglers exist because there’s demand.“

But political debate around migrants has been emotional, not pragmatic—in Europe as well as the U.S.—and the sound and fury over the last few years has crippled the EU’s capacity to change. The result is confusion and idleness on the Mediterranean, which only helps the trans-national networks of passeurs, ex-pirates, and their more violent friends.

by Michael Scott Moore

—Stefano Pitrelli helped in Italy; Nur Hassan helped translate from Somali. Expenses for this article were covered by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.