For years, Kenya and Somalia have argued over where their maritime boundary in the Indian Ocean runs. The International Court of Justice in The Hague could now decide who owns the sea, a decision that will only suit one.

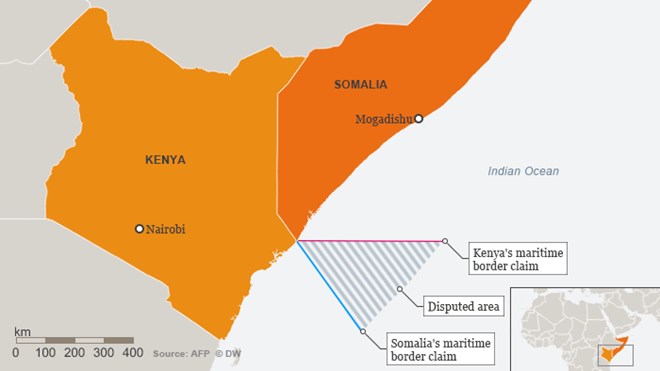

A narrow triangle off the coast of Africa, in the Indian Ocean, about 100,000 square kilometers (62,000 square miles), is the bone of contention between neighboring Kenya and Somalia. Both countries want the area because it supposedly has a large deposit of oil and gas, but it’s not clear to which country it belongs.

“The position of the boundary is a gray area,” said Timothy Walter, a maritime border conflict researcher at the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) in South Africa.

For Kenya, however, the boundary is quite clear. It lies line parallel to the line of latitude. That gives Kenya the larger share of the maritime area and it has already sold mining licenses to international companies. But Somalia disagrees.

The Somalis want the boundary to extend to the southeast as an extension of the land border. In 2009, both countries agreed that the United Nations commission in charge of mediating border disputes should determine the border line once and for all. They also agreed that they should continue to work together to find a solution so that the matter would not have to go to court.

Somalia sues, Kenya protests

That does not seem to have worked – at least from the Somali perspective. In 2014, Somalia sued Kenya at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague. The court represents one way of solving border conflicts in maritime areas if bilateral or regional attempts fail.

The Somali government wrote in its lawsuit that that was exactly what had happened. “The parties met numerous times to discuss how the dispute can be settled. But no progress was made in any of the meetings,” the government said.

Somalia has long been considered a failed state without a functioning government. It has only had an elected president again since 2012 and now seems anxious to safeguard what it regards as its sovereign rights in the Indian Ocean.

Somalia wants the ICJ to define the boundary as laid down by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and other international sea laws.

In disputed cases, a temporary boundary is drawn along a line that is at the same distance from both coastlines, if there are no physical obstacles to this. A test period is then implemented to see if this boundary is fair to both sides or if it benefits or disadvantages one or the other.

Kenya’s government, however, is sticking to its preferred border demarcation. For nearly 100 years, it had considered this line to be its border, the government wrote.

Since Kenya and Somalia had agreed to settle the dispute out of court, Kenya appealed to the court in 2015 opposing the litigation. The court now wants to hear both sides, beginning Monday and will then decide whether it will initiate proceedings.

Only one winner

If court proceedings are opened, then the decision on the border will be binding. Walker thinks that a court case is a high risk for both states. “If the court should decide in favor of Somalia, the Kenyan border would shift dramatically,” he said.

This could lead to a dispute over the maritime boundary with Kenya’s southern neighbor Tanzania, which could in turn have an impact on Mozambique, Madagascar and South Africa.

A compromise is possible, of course, at least in theory: “Both countries could share the area and the mining of raw materials,” Walker said. He said there is a good example in West Africa, where Nigeria and the archipelago of Sao Tome and Principe teamed up to produce oil.

But for Somalia and Kenya, Walker does not see any chance. “Both countries do not want to make any compromise when it comes to their own sovereign rights. That can change, of course, but at the moment, it looks like an either-or decision,” he said. Walker estimates that the decision will be made next year.

Sea-blindness is over

Overall, experts like Walker are observing a growing trend for states, especially in Africa, to take an interest in setting their maritime borders. Walker calls it the “end of the sea-blindness.”

“Most African states lack a substantial navy or a coastguard and many conflicts have spilled over land boundaries or land borders. So historically, there has always been a focus on what is happening on land. Now, that’s changing because what we can see more and more is the resources from the sea are more accessible now through better technological processes,” Walker said.

To the west of the continent, Ghana and Ivory Coast are engaged in a similar conflict about their boundary in the Atlantic Ocean. The two countries are currently awaiting a decision by the International Tribunal for Law of the Sea, an alternative to the International Court of Justice, which resolves border disputes between conflicting countries.

East African neighbors Malawi and Tanzania also have a boundary dispute, this time located in a lake. Lake Malawi borders Tanzania and holds huge amounts of oil deposits. But the colonial-era border for Tanzania ends on the bank of the lake.

These are not the only countries waiting to see how the conflict between Kenya and Somalia continues.