The moon is but a faint sliver on this early July morning and, without its glow, sky and sea meld into a darkness so deep that before John Hamilton can clearly see the people he has come to save, he can smell them.

It is the sour stench of human misery. Of sweat, urine, vomit, blood.

He prays it is not also the smell of death.

At sunrise the previous day, Hamilton stood on the bridge of his vessel, the Topaz Responder, and took in panoramic views of the fortified Maltese capital of Valletta. Night gave way to the sight of centuries-old limestone buildings bathed in fiery hues. Ahead lay the opening to the Mediterranean Sea, shimmering in the morning’s new light.

The air was balmy; the waters almost glass still. Perfect for beachgoers and boaters — but not so for Hamilton. For him, these conditions bode danger.

At 50, this search-and-rescue leader knows a more menacing Mediterranean than the one vacationers worship. He’s seen its beloved waters inflict horror, its dark depths become purgatory. The sea that defined his life has turned into the world’s deadliest migration route.

Bad weather the past few days meant relative quiet for Hamilton and his crew, who are patrolling the waters between Libya and Italy. Gusting winds and rough seas deter small migrant boats from setting sail, but the cruel irony is that on a glorious day like this, things can get grim.

A pilot boat escorts the 167-foot-long Responder out of Malta’s Grand Harbor. On board with Hamilton are five team members of the Migrant Offshore Aid Station, or MOAS, a private Malta-based humanitarian organization with a single mission: to rescue people. A doctor and four nurses from the Italian medical aid group Emergency are also onboard, as are a cook and officers and maintenance workers from Topaz Marine and Energy, the company that owns the Responder.

Few know these waters better than Hamilton.

He has sailed them almost all his life, first as the son of a Scotsman who yearned to join the Navy — though circumstances led instead to an Army career — and then as a sailor himself. It was as though salt water coursed through his veins.

But it wasn’t until the late 1990s that Hamilton, who served in the Maltese Armed Forces maritime squadron, first witnessed human desperation.

That was when “irregular” African migration via the Mediterranean began to pick up and Maltese battleships regularly rescued refugees in distress. They were from troubled nations such as Ivory Coast, Liberia, Somalia and Eritrea and boarded boats from Morocco and Tunisia to reach Spain and Italy.

Two decades later, people from all over Africa and parts of Asia set sail from Turkey, Egypt and Libyan ports to make the treacherous crossing.

They are refugees and economic migrants fleeing homelands ruptured by war, repression and poverty. Their journeys are perilous in overcrowded wooden fishing boats and flimsy polyurethane dinghies hardly suitable for crossing a river, much less a vast sea.

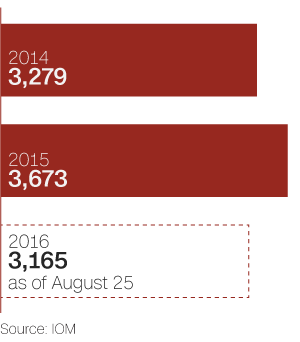

They risk everything for a chance at freedom and dignity. Many perish. This year alone, more than 3,000 have died or gone missing in the Mediterranean. The International Organization for Migration does its best to keep count but the actual numbers are probably much higher. How many boats are never spotted? How many people are never fished from the sea?

Hamilton fears this year may end up the worst on record.

John Hamilton guesses that many of the people he rescues have never seen the sea before, and are unaware of the potential dangers.

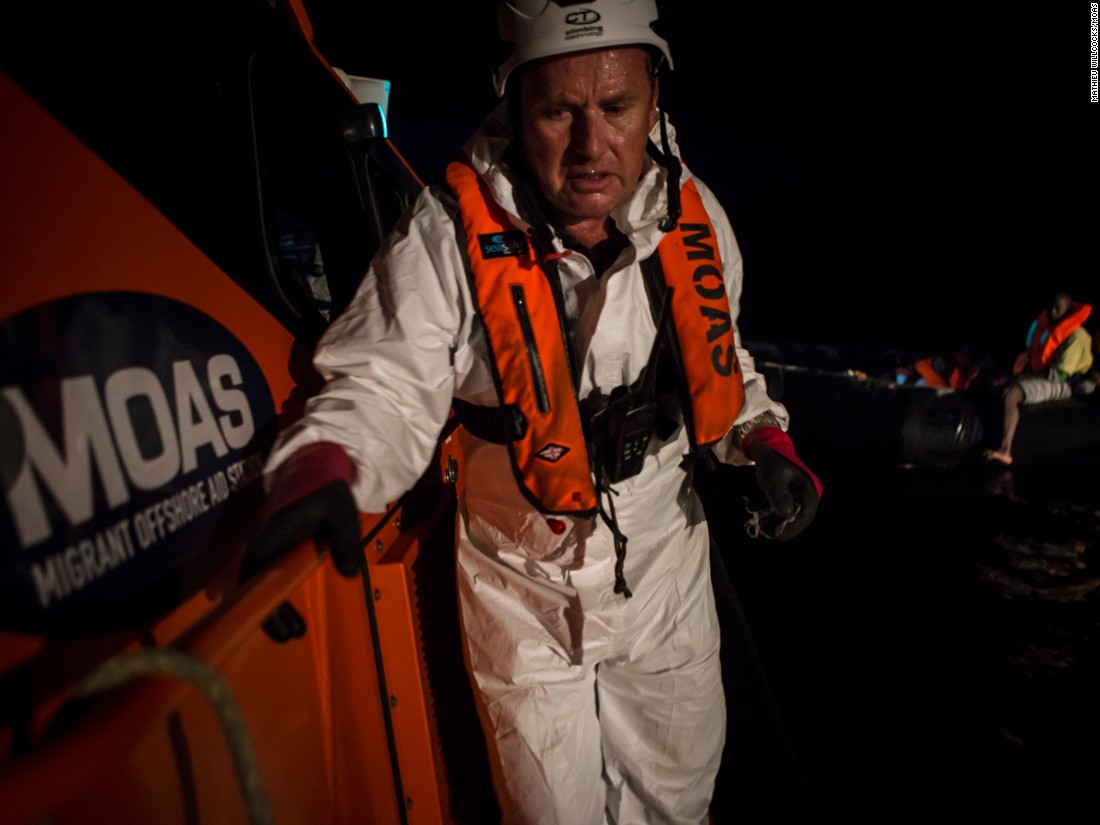

The sun begins lifting higher in the sky and pierces the many windows on the Responder’s bridge. Hamilton’s weathered face appears even ruddier in this light. He came out of retirement and returned to what he did best as a warrant officer, trading his uniform for shorts and a navy blue polo emblazoned with the MOAS logo.

He looks out over the main deck, outfitted with two fast rescue crafts painted the same loud orange as hundreds of life jackets stuffed into giant bags. The high-speed crafts bear the names Alan and Ghalib, the Syrian brothers who drowned in September 2015. The image of 3-year-old Alan Kurdi’s small body, washed up on a Turkish beach, awakened the world to the severity of the European migration crisis.

The rescuer

John Hamilton, 50, is a search-and-rescue leader with Migrant Offshore Aid Station. He served in the Maltese Armed Forces and has been rescuing people on the Mediterranean Sea for almost two decades.

John Hamilton, 50, is a search-and-rescue leader with Migrant Offshore Aid Station. He served in the Maltese Armed Forces and has been rescuing people on the Mediterranean Sea for almost two decades.

Hamilton isn’t interested in the politics of migration. Without rescue boats, he says, a lot more innocent people would die every day.

The rescued

Mogahid Sabeel, 33, lived through war in his native Sudan and then took part in Arab Spring protests against the government.

Mogahid Sabeel, 33, lived through war in his native Sudan and then took part in Arab Spring protests against the government.

“Things became difficult. There came a point where they wanted to arrest me.”

Sabeel ended up in Libya, where he was locked up, held for ransom and abused by militiamen. Desperate, he paid smugglers $400 to get him on a boat to cross the Mediterranean.

The founders

American entrepreneur Christopher Catrambone and his Italian wife, Regina, were on a luxury yacht on the Mediterranean when they realized their beloved sea had become a migrant graveyard. They felt compelled to actand launched MOAS in 2014. So far, MOAS estimates it has saved the lives of 22,000 people.

Hamilton sees Alan and Ghalib’s names every single day. They remind him of his most shattering moment at sea — one that came on a pitch-black night last January.

He was leading search-and-rescue missions on the Turkey-to-Greece migration route when his team spotted a small boat near the Greek island of Agathonisi. A Turkish smuggler was driving much too fast. He took a sharp turn, hit rocks and capsized.

Two dozen passengers, mostly Syrian and Iraqi families, tumbled into the sea and held on to the bow, the only part of the boat still afloat.

Hamilton heard the moans of the refugees. He knew his crew had to work fast, that babies and children could not endure the frigid water for long. Hamilton sped to the scene and the rescue divers were in the sea within seven minutes.

Three children were tethered to their mothers for safety. One, a 2-year-old boy, was blue in the face. The others, a 2-year-old boy and a 4-year-old girl, were not breathing. Their mothers did not realize the children were dead.

“Your son is no longer alive,” Hamilton told one of them in Maltese, a language close enough to Arabic that the Syrians could understand. The parents’ wails punctured the night.

The 20 others who survived would most surely have died of hypothermia or drowned if the MOAS crew had not found them. But for Hamilton, that night is defined by the three innocent lives gone, a night when he felt God momentarily left his side.

He tells the people he rescues that he’d rather die on land; something about perishing at sea is particularly haunting. Maybe because it’s a silent, lonely death. Maybe because in that moment, amid the vastness of the water, a life can seem so insignificant.

As the Responder sails into open water, messages about migrant boats crackle on the radio. Activity in the central Mediterranean picked up this spring, especially after Turkey struck a deal with the European Union to close the migration route to Greece and countries to the north imposed border restrictions. So far, the summer has kept Hamilton busy.

The Responder hurtles in a southwesterly direction, its two Caterpillar engines churning at 1600 RPMs. Hamilton puts down his binoculars, reaches for a mug of tea and settles in for yet another journey of unknowns.

An intensifying crisis

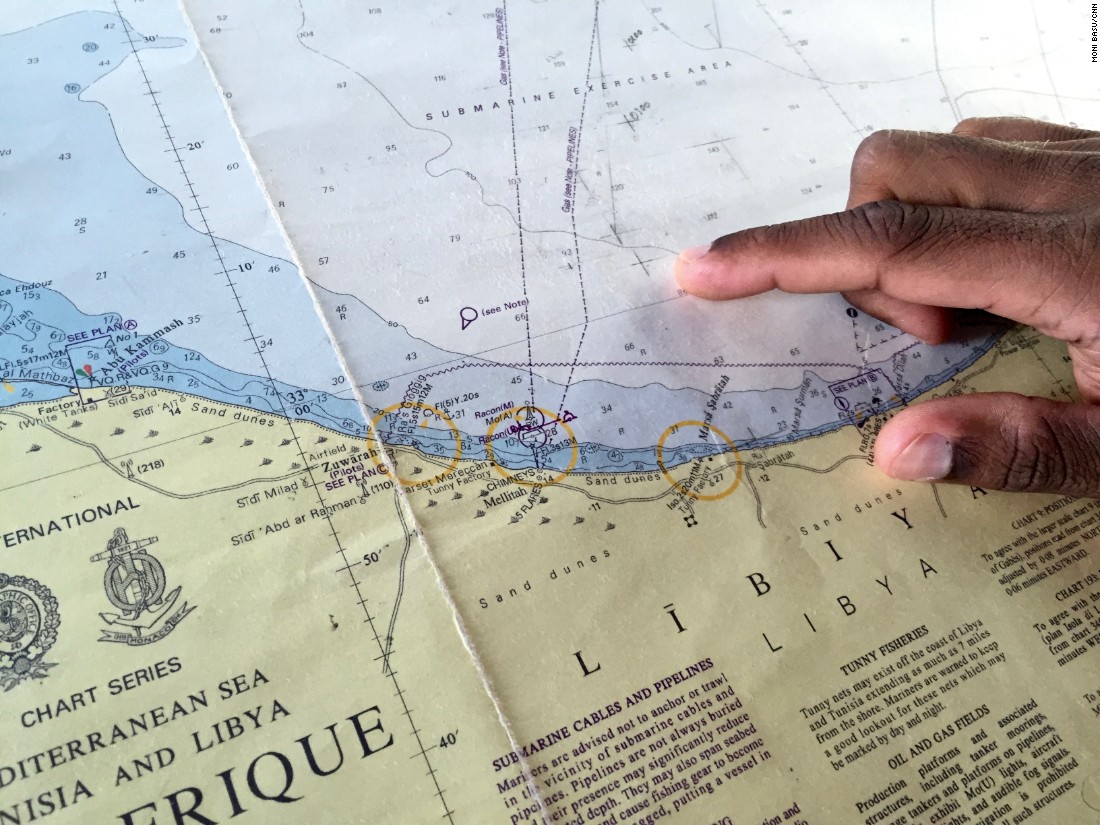

It’s dark by the time the Responder approaches “the zone,” waters close to the Libyan coast between Zuwarah and Sabratha, cities west of Tripoli that have become migrant hubs. The ship draws close enough to land for Hamilton and his crew to see flames from oil refinery smoke stacks.

There are other rescue vessels in the area operated by Frontex, the European Union border agency, and humanitarian organizations like Sea Watch and Medecins Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders). All must stay at least 7 miles from the coastline; anything closer is Libyan territory.

Libya’s descent into anarchy helped boost a lucrative people-smuggling business. African migrants who reach southern Libya are transported through the desert to northern beaches where they board boats bound for Europe. Many are told they will reach Italy in a matter of hours. The reality is the trip to the Italian island of Lampedusa, the closest European territory to the North African coast, takes at least 40 hours in small boats that sputter along at 5 miles per hour.

Deaths at sea

This year is on track to be the deadliest in the Mediterranean.

Hamilton’s heart grows heavy when he talks about Mare Nostrum, or Our Sea, the name the Romans gave the Mediterranean.

“Why should innocent people have their lives at risk because they don’t know the dangers of the sea?” he asks.

He guesses that many of the people he rescues have never seen a seemingly infinite body of water before. Maybe they come from a landlocked country like Mali, Niger or Ethiopia, or from a remote interior village in Sudan or Nigeria. How tragic that their first glimpse of the sea should become their last.

Hamilton spent 27 years of his life on Maltese military ships patrolling the Mediterranean. When he retired in early 2014, his wife, Mary, told him he wouldn’t be able to stay off the water. And as hard as he tried to lead a leisurely life on land, Mary was right.

His adventure with MOAS began when a young American multi-millionaire, Chris Catrambone, founded the rescue operation with his Italian wife, Regina. The couple spent $8 million of their own money transforming a 1973 fishing trawler, the Phoenix, into a search-and-rescue vessel equipped with two remotely operated helicopter drones with HD video cameras that would vastly widen the search for migrants at sea.

Hamilton was moved by the couple’s commitment; that they would spend their own fortune to save lives. He helped sail the Phoenix from Virginia back to Malta and led its maiden mission on August 30, 2014; its first rescue was a wooden boat carrying 320 Syrians and Palestinians.

A little after 7 in the morning, the MOAS Responder spots a rubber dinghy packed with 125 people.

By the time 2014 ended, 3,279 people were dead or missing in the Mediterranean. Last year, the number soared to 3,673, and MOAS chartered the brand new Responder from Topaz Marine and Energy to join the Phoenix.

MOAS estimates it has saved the lives of 22,000 people since it began operating.

Hamilton doesn’t pretend to know how to prevent the deadly sea treks. He just knows one thing: The migration crisis is intensifying.

He understands that horrendous circumstances propel people on their journeys. He mentions Syrians fleeing protracted war and the minority Yazidis of Iraq, hunted by ISIS militants.

“But I wouldn’t do that crossing,” he says. “Not even on my own, never mind my family. These crossings are nothing but fatal.”

Hamilton guesses a backlog of people have been waiting for the weather to clear and are now getting ready to depart from various beaches on the Libyan coast. He can’t see them, but he knows they are there. They always leave in the dead of night so they can slip out unnoticed in the dark.

There isn’t anything for his crew to do but wait.

Hamilton goes to bed early. By 9 p.m., he’s tucked into his bunk. His hunch: He will need all his energy at daybreak.

For $400, a dinghy and danger

A few miles directly south of the MOAS ship, hordes of people collect themselves on Libyan beaches for the crossing. After long journeys by land, their moment of reckoning has finally arrived.

They are herded from walled-in compounds to the surf by Libyan smugglers wielding AK-47s.

One of the migrants is Mogahid Sabeel of Sudan.

Sabeel tried to sleep on the dirt floor of a warehouse where he had been taken but he was too anxious, cold and hungry — it’s Ramadan and he’s been fasting since sunrise.

The smugglers promised Sabeel that his $400 would buy him passage on a cargo container ship or a fishing trawler. There are no such vessels in sight; only a 20-foot-long inflatable dinghy powered by an outboard motor.

Sabeel can tell the dinghy poses danger But by now, his fear of the Libyan militias and smugglers outweighs the risks on the open sea.

He asks for a life jacket.

Yes, yes, you will get one, the smugglers say. They also promise a satellite phone for emergencies.

No more questions, they yell, pointing their guns. They toss five or six plastic jerry cans of fuel into the boat.

It is 2:30 in the morning when Sabeel marches to the water’s edge with 75 men, 53 women and four children. They are ordered to take off their shoes and carry the dinghy out into the surf. The smugglers arrange them in three rows. Those on the outside edges of the boat place one leg in the water and one leg inside. Some of the women lie down in the center with people on top of them so that 133 people can squeeze into a dinghy built for 25.

The human arrangements almost resemble the drawings of people packed into the slave ships that once sailed to the Americas, only on a smaller scale.

One of the smugglers hops into the dinghy, starts the motor and steers the migrants out to sea. After an hour he gets off and boards a fast boat that has arrived to take him back to land.

“See those stars,” he says, pointing upward. “They mean north. Follow them.”

Suddenly ocean and sky are the same color: black.

There are no life jackets, no working phone. No water. No food.

Reality descends with such a heavy crush that most people cannot even panic out loud. They sit silently, too afraid to utter a word. They drink salt water to quench their thirst.

Sabeel sits in the stern, his right leg in the water — and begins to tremble. He is 33, too young to die.

Already, he has endured so much. From his native Sudan he has traveled many months and through three countries in search of a better life.

A bloody civil war ended his plan to run the family farm in Darfur; his family abandoned their land to escape the bloodshed and moved south to start anew. That venture ended, too, after South Sudan gained independence in 2011 and internal conflict ensued.

Sabeel, who studied agricultural science at the University of Gezira, tried his hand at small business enterprises in Ethiopia and Dubai but struggled. He finally fled to Cairo in 2014 after being targeted in Sudan for his participation in Arab Spring protests. He thought of himself as a liberal Muslim and was sure he would face arrest back home.

He heard the employment situation was better in Libya and paid money to enter the country illegally, but things didn’t go as planned and he fell into the hands of militias and smugglers. He says they demanded more money, held him hostage and locked him up for days at a time. After weeks of harrowing experiences, he managed to make it to his cousin’s house in Tripoli.

But he knew he couldn’t stay in Libya. The political vacuum after Gadhafi opened the way for militias and even ISIS to establish power. The few jobs that were to be had were hardly stable. He lived in fear of being abducted or killed.

He learned that ships left Libya for Italy, so he put two shirts, a pair of shorts and underwear in an etched leather shoulder bag made by an artist friend in Sudan and arranged for passage. Smugglers sent a driver in an old white Nissan Maxima who took him and two other Sudanese men west along the coast. They maneuvered through checkpoints until Zawiyah, where they changed cars and routes to avoid heavily armed militiamen. They finally made it to the warehouse in Sabratha at about the same time that John Hamilton was going to bed on the Responder.

Now, under the stars, Sabeel tries to calm himself. If only they can get to Europe by some miracle, maybe someone will recognize his college degree and he can finally make a decent living. But two hours have passed and behind him, he can still see the lights of Libya. In the bow, one of two plywood reinforcement boards is beginning to crack from the weight of the passengers. The boat is listing.

2nd Officer Danny Sebastian points to the Responder’s location. Rescue vessels stay away from Libyan waters.

2nd Officer Danny Sebastian points to the Responder’s location. Rescue vessels stay away from Libyan waters.The stench of human misery

The first blip on the radar comes at 3:45 a.m. Everyone on the Responder jumps into high gear.

A drone is dispatched from the nearby MOAS sister ship, the Phoenix. It is a military-grade Schiebel drone with an infrared camera capable of spotting vessels at night. Almost 70% of the migrant boats MOAS rescues are located by drones that scour the sea.

Hamilton and his rescue team cover themselves with white protective jumpsuits, helmets and life jackets and report to the main deck. The medical staff does the same — it’s important to maintain sanitary conditions onboard, especially when picking up people with unknown or undiagnosed illnesses.

The Responder races toward the coordinates pinpointed by the drone. Hamilton orders the Ghalib, one of the fast orange rescue crafts, lowered into the sea. He hops in with a certified rescue diver, Nick Romaniuk.

Romaniuk gave up a profitable commercial job after his experience at a refugee camp in Greece. There, he met a Yazidi boy in a Sesame Street shirt who’d been thrown into a fire by ISIS fighters and bore scars up and down his arms. A week later, Romaniuk signed up with MOAS.

The Responder’s searchlight finally has the migrant boat in sight. It is nothing but a small dinghy with people packed together in the heat. The smell is pungent; they had nowhere to relieve themselves, and some are sick from the motion. Others are bleeding from injuries suffered in their journeys to this moment.

Hamilton and Romaniuk begin throwing life jackets overboard. That’s always the first step, in case the dinghy capsizes during the rescue. The migrants clamor after every jacket tossed into the air, thinking each may be the last.

Romaniuk boards the dinghy, sits in the bow and tries to keep everyone calm. If his English compatriots who spew hate toward migrants could be here now, he thinks, they too would jump in the water to save someone.

Hamilton decides the sea is calm enough to maneuver the dinghy to the Responder and unload the people directly, instead of moving them onboard the Ghalib.

“Listen to me,” he shouts. “What we’re going to do is bring this boat next to the big boat so I need for you to put your legs inside.”

The migrants move around and some try to stand up. The dinghy rocks from side to side.

“Stay calm,” Hamilton yells again, knowing most of the migrants probably can’t understand English. “Don’t stand up. Sit down. Don’t fight. Everybody, shut up.”

He hates having to be aggressive with people who are so vulnerable, but there is no other way to control the situation. The dinghy could capsize, or someone could fall into the water and get crushed between the boats.

As the dinghy comes alongside the Responder, everyone tries to get out all at once.

“Wait, wait,” Hamilton tells them. “There is no hurry. You are all safe now.”

One by one, 108 people are pulled out of the dinghy, starting with the children and women. Hamilton waits anxiously.

At times he has watched a migrant boat empty only to expose the bodies of those who have died of suffocation, dehydration or sheer exhaustion. On this morning, he feels relieved.

Everyone has survived.

Many migrant families make the risky journey by sea with their young children.They are from Africa: Ethiopia, Gambia, Guinea, Senegal, Nigeria, Mali.

Many migrant families make the risky journey by sea with their young children.They are from Africa: Ethiopia, Gambia, Guinea, Senegal, Nigeria, Mali.One man wears nothing but underwear. Another has on a gray North Face puffer jacket intended for winter slopes. Most are barefoot, their ebony legs powdered with a white mixture of dust and encrusted sea salt. They carry few possessions — a toothbrush tucked in a chest pocket, a plastic pouch containing photos of loved ones left behind.

Three Muslim men face east toward Mecca and fall to their knees in prayer. A Catholic man makes the sign of the cross.

The MOAS crew pats down the men to make sure no one is carrying a weapon or cigarette lighter. The Emergency nurses ask if they have any injuries. One man from Guinea says smugglers beat his legs with an iron bar.

Nurse Yohanes Ghebray leads patients into an exam room set up inside the ship’s cabin. He knows the plight of the migrants. He was one himself years ago when he fled his native Eritrea on a rickety boat and was rescued in similar fashion.

He is assisted by Jean de Dieu Bihizi, who studied philosophy at home in Burundi but felt it wasn’t enough to theorize about the world’s problems — he needed to do something more practical. He remembers a rescue in which two women from Mali looked him in the eyes and said: If we die, please take our children and make sure they are educated. Bihizi was taken aback by their trust.

Inside, Dr. Mimmo Risica scribbles a number on red masking tape and sticks it on the chests of the most serious medical cases. When the Responder transfers the migrants to another vessel or docks somewhere in Italy, doctors will tend to the tagged patients first.

Risica is a retired cardiologist from Venice, a quiet man who volunteered time to do something good and brought with him a hunk of his favorite Parmigiano-Reggiano that he shaves onto his pasta every night at dinner. He stays remarkably calm as he sees patient after patient.

Soon, one third of the Responder’s main deck is filled with people. But the day is young. Hamilton senses more will come.

‘Where are you taking us?’

At 7:10 a.m., the helicopter drones confirm two more boats near the Responder’s location. One — carrying Mogahid Sabeel — is 17 miles north of the Libyan coast.

It’s daylight now but Sabeel cannot figure out what to make of the Responder. His fellow passengers think it’s a Libyan pirate boat and are frightened they will be taken back to Libya or killed and left to rot at sea. They scream at their driver to steer west, away from the Responder.

But then, they see “MOAS” written in English lettering on the ship’s side.

As the Responder gets closer, the migrants spot the fast rescue craft Ghalib descending into the water. They see white people standing on deck. They realize the ship is European.

Sabeel glances at his rapidly draining mobile phone: It’s 7:35 a.m. As the rescue craft rushes toward them, he feels a kind of solace he has not known in many months.

He sees Hamilton standing near the bow of the Ghalib and sees life jackets flying through the air. Then the Ghalib nudges the dinghy toward the Responder. One by one, the migrants board the MOAS ship. First aboard are the Nigerian women. Their knees have locked up from hours of sitting and they limp across the deck, begging for water. Sabeel is one of the last to be pulled out.

The Responder brims with humanity; 366 people rescued on this morning.

Their faces show shock, disbelief, anxiety and relief.

“Where are you taking us?” they ask.

Sometimes rescued migrants are transferred onto bigger vessels in the area. Other times, the Responder transports them to a port in Italy, where they are processed at immigration centers. Hamilton is waiting for instructions from the Maritime Rescue Coordination Center, the agency in Italy that oversees traffic in the Mediterranean.

The Responder’s main deck fills quickly with people rescued at sea.

Almost everyone rescued today says their families paid large sums of money — as much as $5,000 — to smugglers. For many, the money was their life savings.

Bada Mbye, 19, left home in the Gambian capital, Banjul, after his father was arrested for political reasons. He traveled through Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger to reach southwest Libya. He’s wearing a bright red England shirt and says he wants to become a famous footballer in Europe, maybe in Berlin where he has an older sister.

He echoes others when he talks about the abuse inflicted on black Africans in Libya, documented recently by the human rights group Amnesty International. Traffickers and smugglers are known to rape, abduct and torture migrants. The migrants also face religious persecution and exploitation by employers.

Esther Iroghama and her brother traveled by road from Nigeria’s Edo state to Libya. Smugglers put them in the back of a pickup truck but somewhere in the desert, gunmen fired shots at the tires and then at the body of the truck. She survived; her brother did not.

There are about 30 Bangladeshis who paid labor agents up to $2,500 to take them from their impoverished villages to work in Libya’s ceramics industry. They fled after being forced to work without pay.

“I am one of the lucky ones,” Sabeel says, looking around the Responder’s main deck.

He tiptoes over people to refill a plastic water bottle from a container on deck. He gazes across the Mediterranean.

Somewhere out there is Europe.

“At least now,” he says, “I will go to a civilized place and be treated like a human being.”

‘Maybe we would have made it to heaven’

From the Libyan coast, it can take the Responder up to 36 hours to reach a port in Sicily. That’s a long time to sit on a hard surface in close quarters. By the second day onboard the Responder, many of the rescued migrants have grown visibly restless.

The Emergency crew hands out soda crackers and raisins but there are no facilities on board to serve meals to this many people.

Hamilton steps out on deck when it’s his turn to keep watch. He says hello to Mbye, the young Gambian man wearing the England football shirt.

“Don’t play for England,” Hamilton jokes. Everyone around laughs. They know about England’s humiliating defeat by Iceland in the Euro Cup. Hamilton enjoys the joviality amid an otherwise grim atmosphere.

“I like to support underdogs like Iceland,” Hamilton tells them. “But most of the time I support Malta and Scotland. My father is Scottish.”

Sabeel has been listening to the conversation and is eager to meet Hamilton.

“My favorite movie is ‘Braveheart,'” Sabeel says of the Mel Gibson blockbuster.

Suddenly, a commotion breaks out on the ship. Hamilton fears that a fight has erupted and is happy to see he is wrong: People are climbing over each other to glimpse a school of dolphins swimming alongside the Responder.

“I see dolphins as good luck,” Hamilton tells Sabeel. “When I see them, we always come across a migrant boat.”

Hamilton asks Sabeel about the situation in Libya and the smugglers who put him on the dinghy. He tries to understand why people take such enormous risks.

“They are very dangerous, the rubber dinghies,” Hamilton says. “Last week, 10 women died because the front part punctured.”

“Actually, if I had known how dangerous, I would not have gone through this,” Sabeel replies.

“Yes, everyone says that to me. If I were in your situation, I might have done the same as you, only I wouldn’t cross the sea because I know that I would never make it.”

Sabeel describes how they were forced to get on at gunpoint.

“It’s like the trains to Auschwitz,” Hamilton says. “People were forced into carriages and trains. They were like sardines.”

“History repeating itself,” Sabeel says.

“The thing is, people in Europe don’t really know what is happening out here. They just see the boatloads coming,” Hamilton says.

He tells Sabeel he once came across two boats that had capsized with 500 people onboard. Among the survivors was a Syrian doctor who lost his wife and three children.

“It makes you sad because, alright, he survived, but then what is he going to live for? He wanted to go to Europe for a better life, and he lost his family. Now he’s on his own and has to start a new life.”

Sabeel considers the uncertainty clouding his own future. What if he cannot leave Italy to join his brother in France? Or worse, what if he is deported back to Sudan?

On the port side of the ship, the tip of Sicily comes into view. The sight is an instant boost.

“We are relieved to see Italy,” Sabeel says.

“Life is hard in Europe,” Hamilton tells him. “Europeans want you to integrate, observe the laws and observe basic things like sanitation. If you are willing, you will get there.”

“Yes, I have heard of this saying: When in Rome, do as Romans do.”

“So do you think your rubber boat would have made it to Sicily?”

Sabeel smiles. “Maybe we would have made it to heaven.”

Hamilton always tells people to get word back to their home countries about how dangerous a migrant’s journey can be. He encourages Sabeel to talk about his ordeal.

An hour passes. Hamilton’s shift on deck is over. Sabeel extends his right hand.

“Thank you so much, John. You saved my life.”

The rescued migrants are given space blankets that help keep them warm at night.

The rescued migrants are given space blankets that help keep them warm at night.Wishing for an end

At night, the deck of the Responder looks like Reynolds Wrap. The rescued migrants huddle in space blankets, plastic sheets layered with vaporized aluminum that shield them from brisk sea winds and help retain body heat.

People have arranged themselves horizontally on wooden palettes as perfectly as a jigsaw puzzle, making use of every square inch on the main deck. They are so exhausted that no amount of discomfort can prevent sleep.

Hamilton surveys the new faces and ponders the conditions that prompt people to undertake such desperate measures. So many countries with so many problems. The European Union should focus on why people are fleeing, he thinks, instead of putting up walls.

SAVED AT SEA

July 6: 3.5 hours, 3 rescues, 366 saved

Rescue No. 1

- Inflatable dinghy, detected 3:45 a.m.

- 5 women

- 102 men

- 1 baby

Rescue No. 2

- Inflatable dinghy, detected 7:10 a.m.

- 1 woman

- 124 men

- No children

Rescue No. 3

- Inflatable dinghy, detected 7:10 a.m.

- 53 women

- 76 men

- 4 children

The Responder churns forward and hugs the coastline of Sicily, warmed by the glow of Mount Aetna, the active volcano in the province of Catania. Hamilton wanted to drop his passengers off here but an uptick in traffic has overloaded every migrant processing center in Sicily. The Responder has been ordered to sail nearly 15 more hours north to Crotone, a port on the boot of mainland Italy.

On their second night aboard the Responder, many migrants realize for the first time the vast distance between Libya and Italy. They gasp and shake their heads in conversation as the frightening truth sets in.

More than 100,000 migrants rescued on the Mediterranean have entered Italy this year and Sicily has been branded as the new Lesbos, the Greek island where half a million migrants landed in 2015.

One line of thinking in Europe blames rescuers like MOAS for the rise in numbers. Some European leaders have even suggested that rescue operations are like a “taxi service” that encourages smugglers and traffickers to send more people to sea.

Hamilton has heard the arguments. The thing is, he says, it’s not his job to solve the complex migration crisis. His concern is to save the lives of people who might otherwise die.

“I wish all this would come to an end, that there would be peace and no more crossings,” he says. “And I could retire quietly.”

The next morning, there’s not a cloud in the sky, and the Italian mainland looks almost close enough to touch. The migrants take turns singing national songs and dancing. The smiles on their faces seem reward enough for Hamilton.

For some, the journey has been months long. They have endured much to finally make it to Europe.

And yet, Hamilton knows their ordeal is hardly over. A new journey is destined to begin in a new land, one that may not be as idyllic as envisioned.

More than 50 hours after the rescues, the Responder arrives in Crotone. A hush falls over the main deck. On the dock is a crowd of officialdom, including the Italian coast guard, navy and police. Off to one side are two Italian aid workers with cardboard boxes full of made-in-China sandals for the shoeless arrivals.

The migrants disembark five at a time, starting with pregnant women, children and those marked with red tags for their injuries. Most are somber, but not Mbye, the aspiring footballer.

“Grazie,” he says to the MOAS crew. “It’s my first Italian word.”

Mogahid Sabeel is one of the last to disembark in Italy, where another journey will begin.

Sabeel waits anxiously, almost as though he doesn’t want to leave the ship. There are so many unknowns on land.

When it is finally his turn, he picks up his etched leather bag, his only remaining possession from Sudan, and adjusts his glasses. He walks down the gangplank, his bare feet landing on Italian soil.

Hamilton watches as Sabeel is handed a pair of orange and green rubber flip flops and tagged with a number: 335. He is screened by doctors and vanishes behind a tent.

For Hamilton, it’s the end of this story. Another will begin when the Responder sails back to the Libyan coast. He often thinks about the people he meets onboard, whether they succeeded in establishing new lives in Europe.

Sometimes, he receives a “thank you” note through MOAS. And sometimes, when he’s walking the streets in Malta or Italy and comes across an obvious foreigner, he wonders if that person is someone he saved.

By Moni Basu • Video by Joe Sheffer, CNN