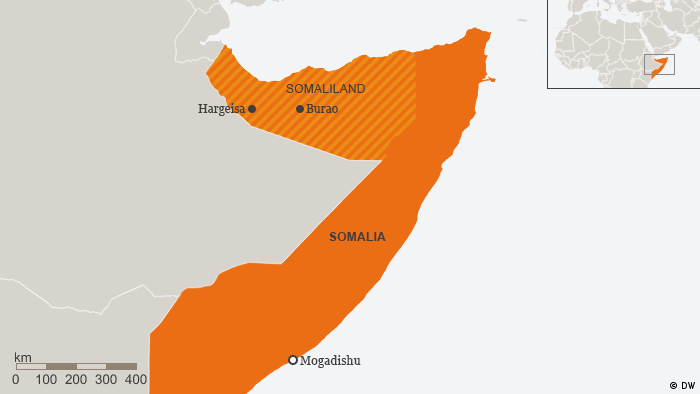

Somaliland broke away from Somalia 25 years ago. But to date, no country recognizes it as an independent nation. It’s battling with poverty, but it is still better off than neighboring Somalia. Twenty-five years after declaring its independence, Somaliland has everything a country would require: An elected government, an army, its own currency and a flag.

Twenty-five years after declaring its independence, Somaliland has everything a country would require: An elected government, an army, its own currency and a flag.

But it’s still not recognized internationally.

“It’s been a strategic decision by international actors and the African Union which is trying to hinder countries from declaring independence, because it fears a domino effect in the region,” Tim Glawion, a research fellow with Germany’s GIGA Institute of African Studies, told DW.

Somaliland broke away from Somalia in 1991 after that country descended into chaos and civil war following the collapse of the regime of dictator Siad Barre. Somaliland was a British protectorate until 1960, while Somalia was under Italian colonial rule. Both then formed a united Somali republic after independence.

AU does not want an independent Somaliland

But while Somaliland‘s leaders think that history gives them every right to go it alone again, other African nations think differently.

“Leaders of the African Union don’t want to encourage an independence of Somaliland because many African countries have borders that were drawn by colonial powers and there are many different ethnic, political or social groups which might feel that they deserve their own country,” Glawion says.

However, Somaliland‘s government is determined not to give up. “Somaliland is a reality. It fulfils all the requirements of a sovereign state and is in full compliance with article 4 of the AU charter regarding the preservation of inherited colonial boundaries,” Somaliland‘s foreign ministry said in a statement in February.

Visitors to the ministry’s website can even sign an online petition calling on the international community to recognize Somaliland.

Camel trade is part of Somaliland‘s economy

Economic woes

The international community’s refusal to recognize Somaliland was “unfair,” Foreign Minister Sa’ad Ali Shire told Germany’s Frankfurter Rundschau newspaper in July.

It would also deprive Somaliland of the chance to develop, he said.

The World Bank put Somaliland‘s Gross Domestic Product at $347 (306 Euros) per capita in 2012. That would have been the fourth lowest in the world at the time, putting it in a league with Malawi, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Burundi.

Unemployment stands at 72 percent for men and a staggering 83 percent for women. With little foreign investment, many residents survive with the help of remittances from abroad. Life expectancy stands at about 52 years. Somaliland‘s government hopes that expansion of the port of Berbera will stimulate the economy.

Somaliland‘s government hopes that expansion of the port of Berbera will stimulate the economy.

But its hard for Somaliland to find investors as long as it’s not recognized.

“For investors it’s very difficult to go there. If you want to extract resources for example, you have to go to the recognized government to sign the treaties, not to some political entity which might in fact control the area but is not recognized internationally,” GIGA’s Glawion says.

There’s however some light on the horizon. A $400 million deal with Dubai’s DP World company will see Somaliland‘s main port of Berbera upgraded to double capacity. International development agencies such as Germany’s GIZ have opened offices in the capital Hargeisa and carry out development programs there as well as in Somalia.

More stable than its neighbour Somalia

Despite its grave economic and social problems, Somaliland has been a haven of stability compared to neighboring Somalia,where is battling Islamist militas and has no control over large parts of the country. Its residents have been to the polls five times since 2001 and were able to experience a peaceful transition of power in 2010. On the global freedom index of US-based Freedom House,Somaliland constantly scores higher marks than Somalia. But that’s not bringing Somaliland any benefits.

“While Somaliland is proving to be a better state every year, its likehood of being recognized is decreasing every year, which is quite a paradox,” says analyst Tim Glawion.