Stories about black masses leaked to press in effort to link paramilitary attacks to the paranormal, study reveals

British military intelligence agents in Northern Ireland used fears about demonic possessions, black masses and witchcraft as part of a psychological war against emerging armed groups in the Troubles in the 1970s, a study says.

Prof Richard Jenkins, from Sheffield University, spoke to military intelligence officers, including the head of the army’s “black operations” in Northern Ireland, Captain Colin Wallace.

Wallace told Jenkins that they deliberately stoked up a satanic panic from 1972 to 1974, even placing black candles and upside-down crucifixes in derelict buildings in some of Belfast’s war zones.

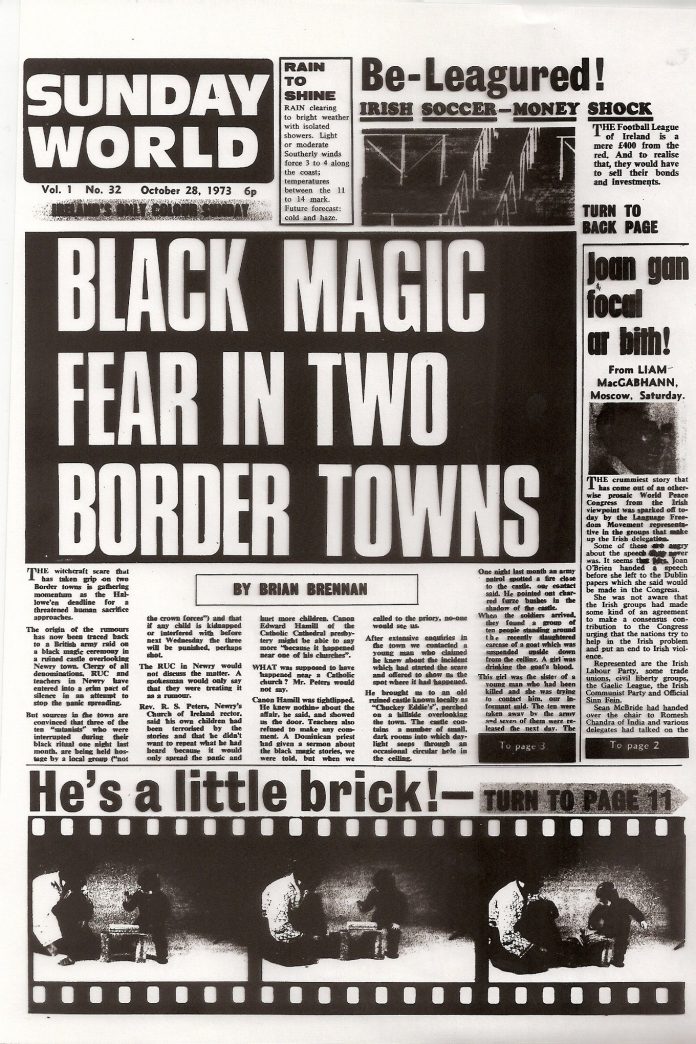

Then, army press officers leaked stories to newspapers about black masses and satanic rituals taking place from republican Ardoyne in north Belfast to the loyalist-dominated east of the city.

In Jenkins’s book, Black Magic and Bogeymen, Wallace admitted that the “psych-ops” branch of military intelligence exploited public fear of satanism stoked by films such as The Exorcist and The Devil Rides Out.

Wallace told Jenkins that by whipping up devil-worshipping paranoia, they created the idea that the emerging paramilitary movements and the murder campaigns they were engaged in had unleashed evil forces across Northern Irish society.

Wallace said his Information Policy group, based at military headquarters in Thiepval barracks, Lisburn, hit upon the idea of summoning the devil as a way to discredit paramilitary organisations.“It was quite clear that the church, both the Roman Catholic church and the Protestant church, even for the paramilitaries, held a fair degree of influence,” Wallace said. “So we were looking for something that would be regarded with abhorrence really by the two communities, and at the same time would be something that paramilitaries couldn’t justify, and also would be in many ways seen as a reason why some of the outrages were taking place.

“That sort of degree of activity was lowering the value of human life. And so eventually it came to the point where we looked at witchcraft … Ireland was very superstitious and all we had to do was bring it up to date.”

Wallace said the manufactured hysteria was also useful in keeping younger children in at night and away from buildings that the military and police might have used for undercover surveillance.

Jenkins, a professor of sociology, said Wallace’s own religious upbringing and cultural background were behind the ideas.

“I think that Wallace and the Information Policy unit had two main objectives. First, it was to encourage a devout population to think that the Troubles had opened a door to ‘dark forces’ and to have them blame the paramilitaries by implication. The logic being: the ungodly paramilitaries caused the violence, the violence has encouraged all kinds of horrible things, ergo the devil, Satan and all that, although I don’t think that was ever going to fly.

“Second, there was the bonus of keeping people, especially teenagers and kids, off the streets at night.”The years 1972-74 were among the bloodiest of the Troubles and a period when Northern Ireland teetered on the brink of civil war. It was also the era when Ulster loyalist paramilitary groups started carrying out ritualistic-style torture killings of Catholics and political opponents.

One of the most notorious of these was the 1973 murder of nationalist politician Paddy Wilson and his friend Irene Andrews.

Jenkins writes that military intelligence sought to create a “subtle” link in the public’s minds between these true-to-life horrors of the Troubles and something more supernaturally evil as part of its propaganda campaign.

Black Magic and Bogeymen: Fear, Rumour and Popular Belief in the North of Ireland 1972-74 is published by Cork University Press.