When the state introduced higher standards for child care, many feared that home-based centers, including those run by women from Somalia, would close. But a group of them joined together to make sure that didn’t happen.

When Somali refugees began arriving in the Seattle area in the 1980s, many of the women created small businesses that tapped their culture’s passion for raising children, and provided them a way to support their families in a new land far from the wars of East Africa.

In those days, they could easily get state licenses to open home-based child-care businesses as long as they offered safe places for children.

Then in 2012, the state launched an ambitious effort to improve the quality of teaching in preschool and child-care centers big and small, based on decades of brain research showing children need much more than baby-sitting to thrive intellectually and emotionally.

But the new requirements made many in the East African community fear the state wanted to shut them down. And the state was worried, too, that many home-based centers would close, making low-cost child care even less available to immigrants who need it the most, and depriving families of their livelihoods.

That started to happen a few years ago as one East African provider after another closed rather than attempt to meet the state’s new expectations.

But thanks to the efforts of a few young child-care professionals raised in the East African community, the trend has reversed.

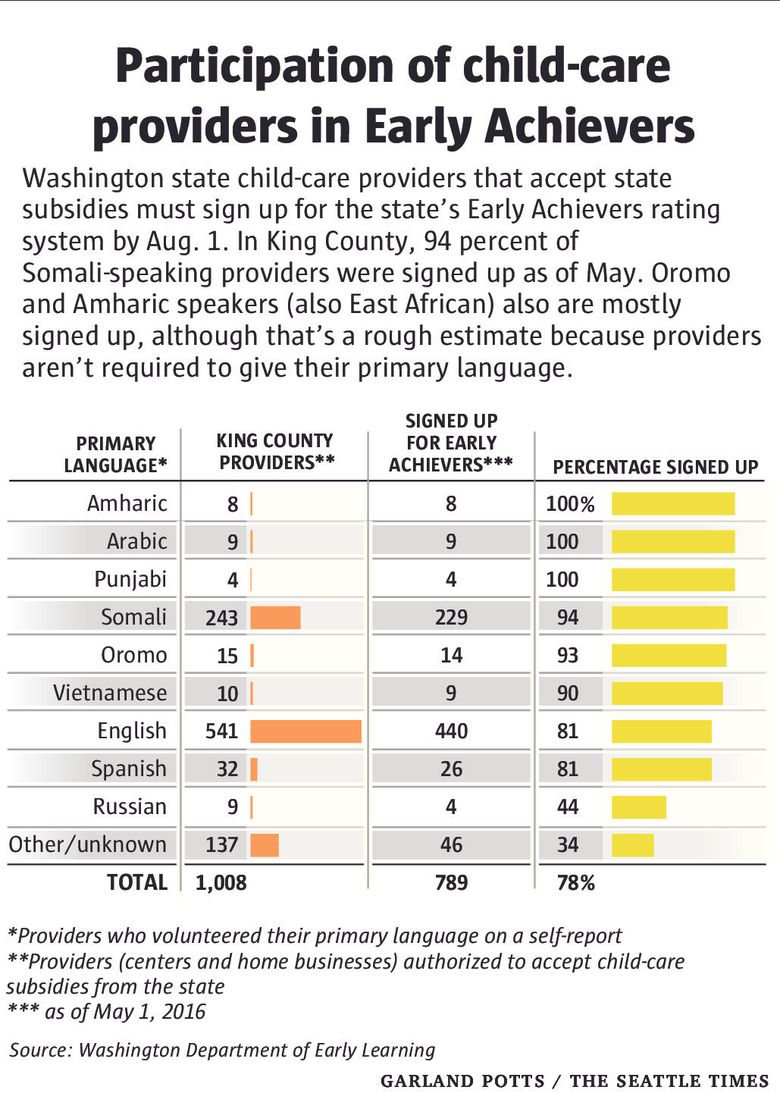

As of May, 94 percent of the 243 Somali-speaking child-care providers in King County had signed up to become part of the state’s effort, called Early Achievers.

That’s way above the county average of 78 percent (which includes preschool centers) and even exceeds centers run by native English speakers.

In King County, where almost one in five children eligible for government-subsidized care is Somali, that’s an important step.

“If you don’t have a solution that addresses Somali kids, you don’t have a solution,” said Ross Hunter, director of the state’s Department of Early Learning, in a new report that features Washington’s preschool program.

Many credit the improvement to a group of young professionals who, with their nonprofit Voices of Tomorrow, arranged for training in East African languages, and earned the community’s trust because of their professional and cultural credibility.

Steeped in culture

Zam Zam Mohamed, one of the co-founders of Voices of Tomorrow, was 12 years old when her family came to the U.S. in 1999, fleeing a civil war inSomalia that had torn that country apart.

She grew up in South Seattle, where she became part of Washington’s Somali community, which one estimate pegs at 30,000 people, and is thought to be the third-largest in the U.S., after Minnesota and Ohio.

Mohamed knew many women who started small child-care businesses, mostly serving families who wanted their children to be cared for by someone from their own culture.

Mohamed herself worked in a bigger child-care center, Tiny Tots Development Center in Seattle’s Rainier Valley neighborhood, where she was the firstSomali teacher. That’s where she met Iftin Hagimohamed, who was later hired at Tiny Tots as a lead teacher and now works for the city of Seattle’s Department of Education and Early Learning.

Their experiences at Tiny Tots — and for Hagimohamed, at the city — put them in a good position to understand what Early Achievers, and its new rating system, was trying to do.

When they realized home providers didn’t have a good grasp of the program, they founded Voices of Tomorrow, with the goal of bridging the gap between the state’s Department of Early Learning and the East African community.

When they started, that gap was wide.

Dealing with the state’s bureaucracy was complicated enough, especially for those who want to offer care to low-income families who receive child-care subsidies from the state.

“The current licensing infrastructure is, at best, not helpful,” said Frank Ordway of the state’s Department of Early Learning.

The state’s arcane system that pays providers for the subsidized children in their care, for example, is, “frankly, indefensible,” he said.

Somali women muddled through the language and culture gaps as best they could.

Initially, they were open to Early Achievers, Mohamed said, which was voluntary at first and provided training in how to promote children’s emotional, social and intellectual growth.

But the training materials were in English, and the program’s goals — and five-star rating system — weren’t made clear to East African providers, Mohamed said.

“There was never a deeper explanation of all the requirements they would have to go through,” Mohamed said. “Once they got in and they saw the process and it became a very arduous journey, they kind of fell off, little by little.”

In 2014, Voices of Tomorrow started offering training in Somali, which made a big difference.

“Three years ago there was nothing,” said Roda Abdullahi, one of the East African providers in King County who together serve about 3,600 children, with 80 to 85 percent from East African homes.

While she was still learning English, Abdullahi would attend training classes but come home realizing she hadn’t really understood what the teacher was talking about.

And she and other East African providers often felt they were the last to know about important changes to state policy and regulations.

Stepping up to challenge

Voices of Tomorrow tried to keep the community in the loop, but its mission became much more urgent in 2015 when the Legislature decided that any provider who wanted to accept state subsidies had to sign up for Early Achievers and receive at least a three-star rating by 2020.

“Everyone was scared of this,” Abdullahi said.

Mohamed and Hagimohamed tapped the expertise of two more young women from the East African community — Ikran Ismail and Asha Warsame, who joined the Voices of Tomorrow executive board in early 2015.

Ismail and Warsame were both working in the University of Washington’s Childcare Quality & Early Learning Center, which had led to the development of Early Achievers.

Because they understood the jargon of early-childhood education, they were better able to explainEarly Achievers in the providers’ own languages.

Even simple things could be misunderstood if translated literally.

For example, some women puzzled over the phrase “red flag,” thinking about a crimson banner, not a potential warning sign in a child’s behavior. And the concept of “dramatic play” made them think of a theater production, when it really meant activities like pretending to make pancakes in a toy kitchen.

Voices of Tomorrow held its first conference in 2015, which attracted more than 200 East African women, and Ismail and Warsame persuaded many to get even more training.

Computers are not widely available in the East African community, so Ismail and Warsame took registration information over the phone. They helped sign up more than 100 women for an Early Achievers conference a few months later, which included classes taught for the first time in Somali.

“All of them are mothers,” said Mohamed. “All of them are caring for the children in their communities: their sisters, their friends, their neighbors. And they want successful children. They want quality care. And we say: Exactly, Early Achievers is the same thing that you want, except it’s in a different language.”

The state has been helping, too, ready to do something if it looked like Early Achievers would create “service deserts” where no subsidized child care is available.

And given Voices of Tomorrow’s success, the state sees it as a model that could help with other ethnic groups.

“It is helping us as an agency to rethink how we engage these communities,” said Genevieve Stokes, Hunter’s assistant at the Department of Early Learning.

State learns, too

Voices of Tomorrow also has helped the state understand Somali culture and make adjustments.

Voices of Tomorrow also has helped the state understand Somali culture and make adjustments.

For example, Somali women don’t sit cross-legged with their students on the floor and it’s considered rude for children to make direct eye contact with their elders.

Early Achievers doesn’t explicitly require providers to do that, but the program focuses on the quality of interactions between teachers and students. Providers who don’t do those things might come across as aloof to an observer who doesn’t understand Somali culture, which could affect their rating.

And Voices of Tomorrow also has helped the East African providers understand the brain science showing that high-quality instruction in the first five years helps prepare children for a lifetime of learning.

“They will take your word over anybody else’s, because you belong to the community, you’re from the community,” said Warsame, who came to the United States in 1996 when she was 7 and grew up interpreting for her mother, who also had a child-care business.

Voices of Tomorrow also encourages women to advocate for their own children in school — and for themselves as small-business owners.

Mohamed also sees a new generation of leaders emerging, and when she addressed about 200 of them recently at Voices of Tomorrow’s second annual conference, she told them to focus on their strengths, because “You are so powerful.”

“Before, nobody ever heard our voices,” said Sabah Saed, one of those emerging leaders who also spoke. “If there were changes, we didn’t even know. “

Now, she said, many feel confident speaking up before decisions get made.

“In Somalia, the government always has the power. Here in America, even though government is telling you the rules, you have a voice,” Saed said. “I never called my licenser before, but now I feel very powerful. If I have a question, I call him.”