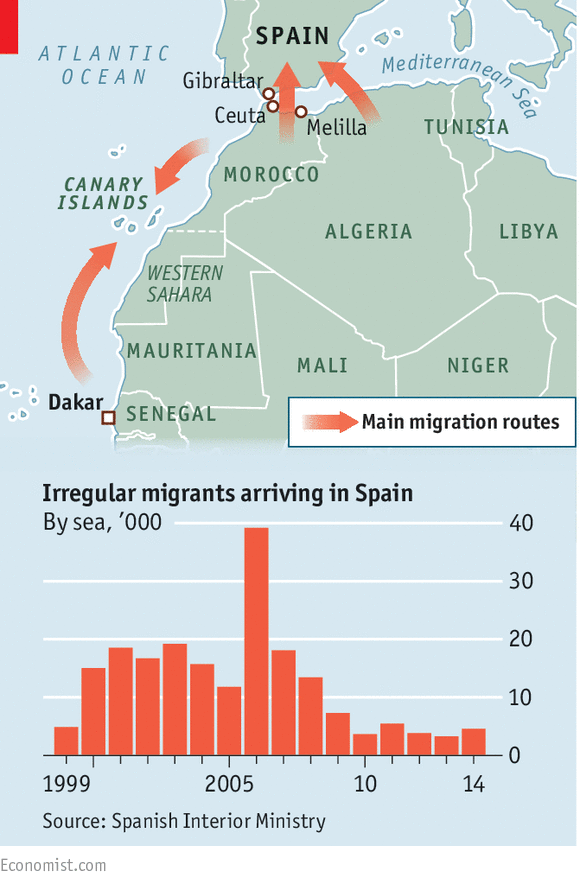

THE rubbish-strewn beach at Hann, a suburb of Dakar, Senegal’s capital, is packed with colourful, canoe-like pirogue fishing boats, ideal for smuggling lucrative human cargo. A dozen years ago the first ghastly scenes of drowned bodies washing up on European beaches featured pirogues from Hann and elsewhere that set out for the Canary Islands, a Spanish archipelago just 60 miles (100km) off the African coast. In 2007, 32,000 migrants reached them by sea. By 2010 the flow had slowed to a trickle, with fewer than 200 reaching the Canaries by sea most years since then. None came from Senegal.

THE rubbish-strewn beach at Hann, a suburb of Dakar, Senegal’s capital, is packed with colourful, canoe-like pirogue fishing boats, ideal for smuggling lucrative human cargo. A dozen years ago the first ghastly scenes of drowned bodies washing up on European beaches featured pirogues from Hann and elsewhere that set out for the Canary Islands, a Spanish archipelago just 60 miles (100km) off the African coast. In 2007, 32,000 migrants reached them by sea. By 2010 the flow had slowed to a trickle, with fewer than 200 reaching the Canaries by sea most years since then. None came from Senegal.

With hundreds of thousands of migrants now arriving elsewhere in Europe, that sounds magical. “Spain has accumulated experience that no other country has,” says Carmen Gonzalez, a migration specialist at the country’s National Distance Education University. But can that experience be applied to today’s surge?

The secret of Spain’s success was co-operation with transit countries such as Senegal, Morocco and Mauritania, says Gonzalo Robles of AECID, the government’s aid agency. As a former secretary of state for immigration, Mr Robles drew up agreements that helped block Morocco as a departure point both for the Canaries and Gibraltar. They included joint maritime patrols backed up by a sophisticated radar system that could detect boats leaving Morocco’s Mediterranean coast, just nine miles away from Spain at its closest, and tip off police. Patrolling the 2,395km of Atlantic coastline shared by Senegal, Mauritania and the Moroccan-run Western Sahara (not to mention Morocco’s own, long stretch) is a task of another order. But the aim is still to catch boats as they leave. Spain has achieved this with only a few dozen of its own frontier police deployed in Africa. Most work is done by local police, who receive Spanish money, equipment and training. “A trained officer can always spot a migrant boat,” says Nicolás Meca, the Spanish police commissioner in charge of the operation in Senegal.

Patrolling the 2,395km of Atlantic coastline shared by Senegal, Mauritania and the Moroccan-run Western Sahara (not to mention Morocco’s own, long stretch) is a task of another order. But the aim is still to catch boats as they leave. Spain has achieved this with only a few dozen of its own frontier police deployed in Africa. Most work is done by local police, who receive Spanish money, equipment and training. “A trained officer can always spot a migrant boat,” says Nicolás Meca, the Spanish police commissioner in charge of the operation in Senegal.

Poorly paid local police, once easy targets for traffickers’ bribes, now receive daily allowances from Spain when on migration watch. That is vital, says Mr Meca, giving him eyes all along the coast. Thirty-metre patrol boats operated by Spain’s Civil Guard police, or donated to their Senegalese and Mauritanian counterparts, are maintained with Spanish money. And a Spanish helicopter with Senegalese police on board watches from the air. A generous development-aid programme has bought additional goodwill.

Traffickers’ boats are intercepted and forced back to shore. Though migrants are rarely arrested in Senegal, their stories of failure and wasted money spread quickly, stemming the flow. One of the few to get through in the early days of the crackdown was 31-year-old Ibrahima Dieme, whose pirogue slipped secretly out of Hann carrying 75 migrants from several African countries. The experience was terrifying and pointless. “From the beach, you think it is calm in the ocean. But you go into the sea and the ocean is huge: the waves are deadly; the storms are deadly,” he recalls.

The crackdown made Mr Dieme’s journey far tougher than the coast-hugging trips of early migrants, as the smugglers tried to dodge patrols by sticking to open sea. A promised 72-hour trip took ten days as fuel ran low. The crew smoked marijuana and jittery passengers threatened to jump overboard. Mr Dieme eventually landed in the Canaries, but fell foul of Spain’s repatriation agreement with Senegal. After spending over two weeks in detention, he was sent home with some money, a sandwich and a bottle of water. The roughly $900 he gave the traffickers is ten times the monthly salary he now earns helping young people find work.

Spain’s economic crash in 2008 further put job-seeking migrants off. With seaborne migration close to zero and a swelling budget deficit, Spain could have shut the operation down. But the agreements signed in 2006 have been renewed each year, blocking the path to new migrants from Syria, Eritrea and elsewhere—enhancing Spain’s relationship with border forces in a region with other security threats, such as Islamist terrorism. Maintaining the programme has required Spain to turn a blind eye to its partners’ dubious democratic credentials. A coup in Mauritania in 2008, later followed by elections, did not change the agreements there.

Money has also gone to helping transit countries patrol their land borders, forming barriers further down the routes that criss-cross northern Africa. And the transit countries have taken a more active approach to managing migration. Last year Morocco gave residency papers to some 18,000 sub-Saharan Africans, making them easier to monitor and integrate. Mauritania, with a population of just 3.5m, expelled 6,463 immigrants last year, up from 713 the previous year.

Mr Robles reckons the lessons learned by Spain can be applied elsewhere. Wide-ranging bilateral agreements that cover policing, aid and the buttressing of state institutions in transit countries are, he says, the key to success. But economic migration from Africa and a flood of refugees from war-torn countries such as Syria are very different, Mr Robles concedes. So, too, is dealing with a shattered state like Libya. On October 15th European leaders were due to discuss a deal with Turkey, including the readmission of failed asylum-seekers.

So far Spain, which has the advantage of being at the far end of the Mediterranean, has avoided Europe’s current migration headache. But it is seeing migrant detention centres in Ceuta and Melilla, two African enclaves encircled with barbed-wire fences, fill up with Syrians who slip through with fake Moroccan documents. Some who have reached the Canaries in small boats that have dodged sea patrols and radars in recent weeks also claim to be Syrian. Officials will not say how much its anti-migration effort costs. But it is much less than Italy or Greece is spending.