Stockmarket turmoil in China need not spell economic doom. But it does raise questions far beyond the country’s shores. THE ability to make stockmarkets boomerang is usually reserved for central bankers. But on August 24th, hours into a global market rout that had started in Asia and was sweeping its way through Europe and then America, Tim Cook, the boss of Apple, turned his hand to it. “I can tell you that we have continued to experience strong growth for our business in China through July and August,” he wrote in an e-mail to CNBC, a financial-news channel. “I continue to believe that China represents an unprecedented opportunity over the long term.”

THE ability to make stockmarkets boomerang is usually reserved for central bankers. But on August 24th, hours into a global market rout that had started in Asia and was sweeping its way through Europe and then America, Tim Cook, the boss of Apple, turned his hand to it. “I can tell you that we have continued to experience strong growth for our business in China through July and August,” he wrote in an e-mail to CNBC, a financial-news channel. “I continue to believe that China represents an unprecedented opportunity over the long term.”

By the time Mr Cook felt it necessary to opine on the state of the world’s second-biggest economy, plenty had started to question its prospects. Following weeks of wobbling, the Shanghai stock exchange had just cratered. A government once credited with near-magical powers to browbeat its economy into growth looked to have misplaced its wand. Suspicions abounded that a decades-long era of superlative—if recently softening—economic expansion might be coming to an end. So the news that Chinese consumers were still in the mood for new iPhones and whizzy watches did more to assuage nerves than reams of official pronouncements from Beijing ever could.

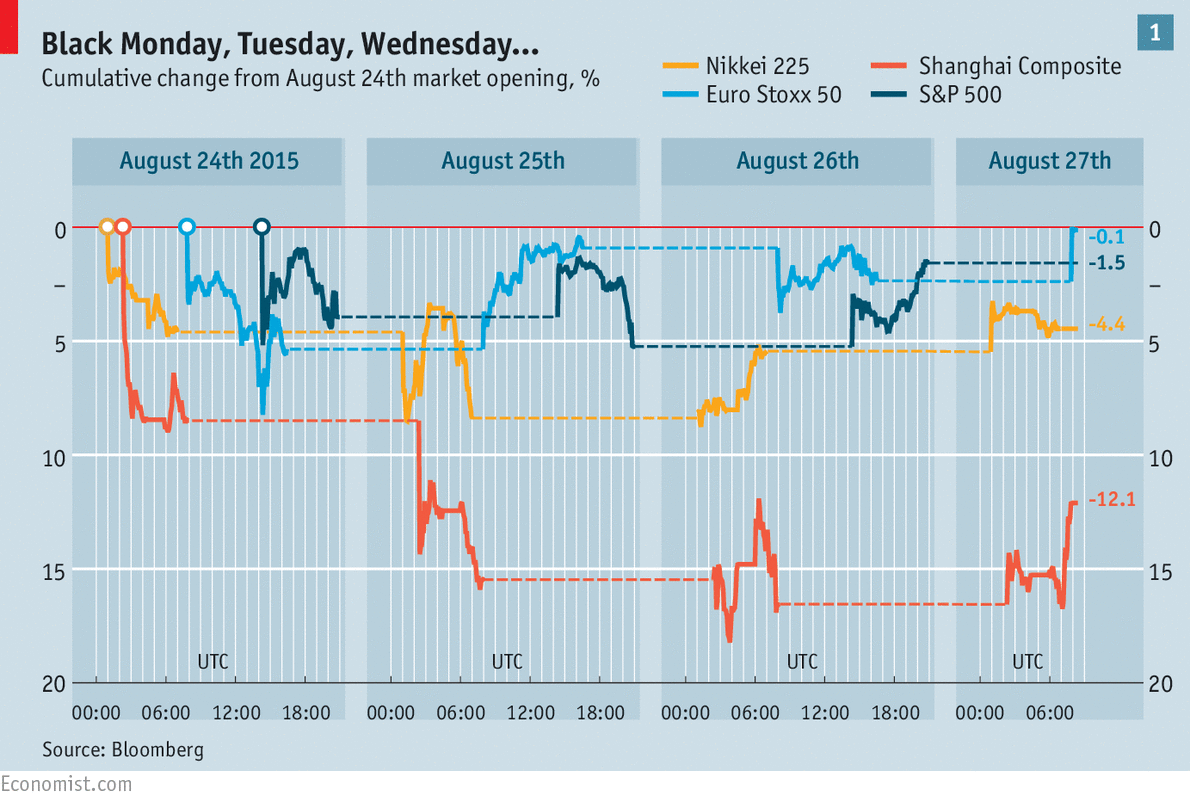

Apple shares reclaimed the $66 billion they had lost; the Dow Jones blue-chip index, having opened down a calamitous 1,000 points, rebounded. But that was a precursor for days of volatility. Many markets around the world crossed the line into “correction” territory, having fallen more than 10% from recent peaks, though some were rallying as The Economist went to press. Shanghai remained down by some 40%, a drubbing to rival the 2001 dotcom crash, if not (yet) the 2008 miasma.

The effect has been felt beyond stockmarkets. A basket of commodities, including everything from steel to wheat, has fallen to its lowest level this century; oil is at six-and-a-half year lows. Emerging-market currencies have been hammered. The VIX index, a measure of fear in markets, jumped this week to its highest level since 2011. The see-sawing in stocks may even have put cracks in the architecture of markets: many exchange-traded funds, which investors use to buy baskets of stocks or other assets, decoupled from their underlying components, trading at nerve-wracking discounts. (Others blamed this on an ill-timed computer glitch.)

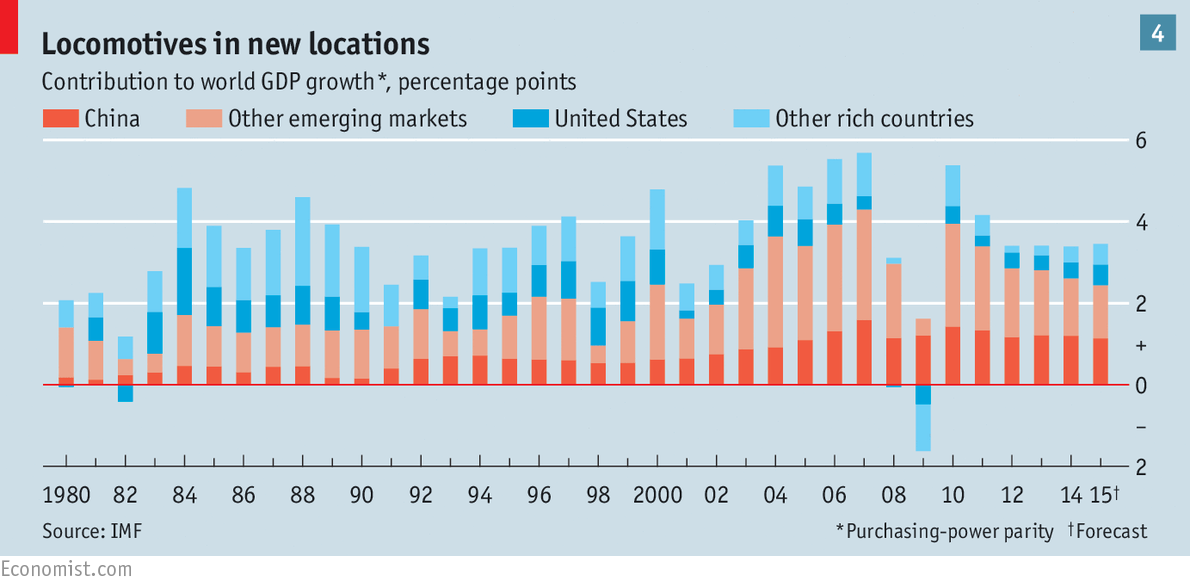

Investors are now trying to delve beyond iPhone shipments and gauge where China’s economy—and so the world’s—stands. In terms of global impact, a “hard landing” in China would now rival an American depression. Countries from Australia to Angola have grown richer from digging stuff out of the ground and shipping it to China. Industries from carmaking to luxury goods look to China for new business. It has been the most stable contributor to world economic growth. Will that continue?

Certainly, there are reasons to think it is in trouble. Exports are stumbling, bad loans rising and the industrial sector at its weakest since the depths of the global financial crisis. Never entirely credible, the government’s claims that the economy is chugging along at 7% now elicit derision.

Even more alarming is the way these stresses appear to be showing through in its markets. On August 11th the central bank stunned investors by devaluing the yuan, whose rate it “guides” through regular interventions. The currency moved more in a day than it does in most months. The devaluation looks to have been a technical change to the way the exchange rate is managed. But thanks to poor communication, many saw it as China’s first fusillade in a global currency war. Markets around the world have been on tenterhooks ever since. Capital outflows from China have shot up as investors have soured on the economy.

And then there is the daily carnage in the stockmarket. The government has thrown at least 1 trillion yuan ($156 billion) at buying shares in order to stabilise them, only to see prices plunge even more violently. The fear is that all this market turmoil speaks to deeper fractures in the foundations of the Chinese economy, with the entire edifice at risk of toppling over.

So is this the hour of China’s crisis? Highly unlikely. Though the economy faces grave problems, the financial tumult is misleading. China’s stockmarket has long been derided as a casino, and for good reason. The bourse is small relative to the economy, with a tradable value of a third of GDP, compared with more than 100% in developed economies. Stocks and economic fundamentals have little in common. When share prices nearly tripled in the year to June, they no more reflected a stunning improvement in China’s growth prospects than their collapse since then has foreshadowed a sudden deterioration.

Less than a fifth of China’s household wealth is invested in shares; their boom did little to boost consumption and their crash will do little to slow it. Punters borrowed lots of money to buy stocks in good times, to be sure, and some of that debt will default. But it amounts to just 1% of total banking assets, a potential hit that, although unpleasant, is hardly systemic.

The property market matters far more for China’s economy than equities do. Housing and land account for the vast majority of collateral in the financial system and play a much bigger role in spurring on growth. Yet the barrage of bearish headlines about share prices has obscured news of a property rebound. House prices have perked up nationwide for three straight months. Two months after the stockmarket first crashed, this upturn continues.

On the downside, there is little chance this rebound will translate into a big acceleration in building activity, because Chinese developers still have to work through a glut of unsold homes, the legacy of their building frenzy of recent years. But the stabilisation of prices reduces the risk of a property-market crash—an event that would be for China what a stockmarket crash would be in America or Japan.

Some think China has, in fact, already suffered the hard landing dreaded by economists. They point to weakness across a broad range of physical indicators used as proxies for Chinese growth because the government’s official data are seen as iffy. Cargo moved by rail has declined, electricity consumption is anaemic and producer prices are mired in deflation. Add it all up, the sceptics say, and China’s annual growth looks to be just 2-3%.

This downbeat assessment oversimplifies the economy. Heavy industry is, without question, struggling. The north-eastern rust belt is on the brink of recession. But China is a continent-sized economy, fuelled by more than just the construction of homes and railways. The service sector, which now accounts for a bigger share of national output than industry, is growing quickly. Retail sales remain strong, as Apple’s Mr Cook was so keen to point out. Economic growth is almost certainly lower than the rate reported by the government. But it appears to be within the range of a soft landing.

Further turbulence would be manageable. On August 25th the central bank cut interest rates and reduced the portion of deposits that banks must lock up as reserves. Even with these cuts, the latest in a months-long easing cycle, benchmark one-year lending rates still sit at 4.6%, while required reserve ratios are 18% for big banks. The central bank looks set to continue cutting both, reducing funding costs for borrowers and freeing up more money for banks to lend. These are the sorts of levers most Western economies do not have.

On the fiscal side, for all the talk of mini-stimulus measures, the government has in fact exercised remarkable restraint. It aimed for a budget deficit of 2.3% of GDP this year, a bit more than in previous years. But as of July it was still in surplus, having raised more in taxes than it had spent. This suggests it still has plenty of petrol in the tank if it wants to rev up growth.

A mess to mop up

Even if China holds up well enough now, there is still the worry that a sharper slowdown lies ahead. The government faces daunting challenges in managing the economy. It is trying to clean up the debt mess left over by the stimulus of 2009, when it unleashed a mammoth investment spree to fight off the global financial crisis.

Debt, by some counts, has reached more than 250% of GDP, almost doubling over the past seven years. Increases of that magnitude have presaged crises in other countries, from Japan to Spain. At the same time structural trends are turning against China. Its working-age population is now shrinking.

A range of reforms could help China tap new sources of growth: allowing private companies to compete properly with state firms; fostering the rule of law to give entrepreneurs more confidence to invest; and relaxing residency controls that stunt the free flow of its people. For the time being, however, these run against the Communist Party’s reflexive need for control.

The turmoil of the past two months has sowed doubts about whether the government has either the inclination or the skill to push through reforms. For all the flaws of China’s political system, many outside the country had viewed its leaders as economically adroit, capable of bringing about rapid growth and snuffing out risks. Now they are not so sure.

The government’s ill-fated response to tumbling markets has severely tarnished that aura of competence. The markets regulator banned short-selling and halted IPOs; traders and a journalist are being probed for spreading rumours. State-owned companies bought back their own shares. The central bank lent cash to an agency that vowed to push the market back up. State media boasted that the “national team” would triumph. It did not. The market sank lower, eroding the government’s reserves as well as its credibility.

China’s stockmarket should eventually find its feet and the devaluation debacle may recede into memory, but the political damage will be lasting. These episodes have raised unsettling questions about the commitment of Chinese policymakers to the market reforms needed to shore up the long-term health of the economy. An unusual editorial in the People’s Daily, mouthpiece of the Communist Party, said last week that Xi Jinping, China’s president, wanted to make deep reforms but had encountered resistance “beyond what could have been imagined”. Some guess that former leaders are pushing back against Mr Xi, who has led an anti-corruption drive that has made him China’s most powerful leader since Deng Xiaoping. Others say that civil servants, fearful of this campaign, are sitting on their hands, afraid of doing much of anything.

Senior government and party officials have said almost nothing about the turmoil, which has fuelled speculation of divisions at the top. The prime minister, Li Keqiang, who oversaw the failed attempt to prop up the stockmarket, is likely to come in for particular criticism.

But Mr Xi himself can hardly escape scrutiny. Unlike most of his predecessors, who left the economy to their prime ministers, the president has immersed himself in economic decisions. He chairs new policymaking bodies on reform and finance. This makes it harder for him to escape blame when things go wrong.

If China does, after a bumbling few months, press on with its reform agenda, it could yet pull off the amazing trick of opening up and modernising its economy without suffering a serious crisis. But even if it succeeds, there will be negative consequences for others. The economy is rebalancing, albeit slowly, away from investment and towards consumption (see chart 3). China still has many more homes, highways and airports to build, but the trend away from them is unmistakable.

Rebalancing act

As a result, its appetite for commodities has probably peaked. That is bad news for companies and countries that prospered over the past decade by selling it mountains of iron ore, copper and coal. A decline in Chinese consumption would be of huge consequence: it absorbs about half the world’s aluminium, nickel and steel, and nearly a third of its cotton and rice.

Arguably worse for some emerging economies than the prospect of a Chinese slowdown is the reality of resurgent American growth. The rich world’s anaemic post-crisis recovery has ensured that global interest rates remain at rock-bottom. The monetary stimulus has been boosted by “quantitative easing” (QE), bond-buying designed to make policy even looser. With bond yields depressed in America, investors piled into emerging-market bonds in the search for decent returns.

The days of cheap American money appear to be numbered. The Federal Reserve’s QE programme was wound down last year and it is now contemplating raising interest rates for the first time since 2006. That prospect has driven up the dollar, which has risen by a weighted average of 17% against the currencies of its trading partners in the past two years and by considerably more than that against emerging-market currencies.

This is a dramatic shift given that expectations of future rate rises in America are modest. But much of the money that flowed into emerging markets was pushed there by the falling yields on offer in America and pulled by the lure of racier returns. Capital has already started to flow out of emerging markets. If and when the Fed increases rates, investors will promptly repatriate more money to America. What sort of landing for the economy?

What sort of landing for the economy?

The countries most vulnerable to such a reversal are those with biggish current-account deficits—in other words those that relied on foreign capital to bridge the gap between what they spent and what they earned from trade. The countries most exposed to shifts in China’s economy, meanwhile, are the commodity exporters who supply the raw materials for the steel girders and copper piping that have underpinned the construction boom.

Brazil suffers on both counts. Its currency, the real, has fallen by more than a third against the dollar in the past year and by almost half since May 2013, when the Fed first hinted that its bond-buying would taper off—prompting a wobble across emerging markets dubbed the “taper tantrum”. Brazil’s central bank has raised rates to 14.25% to tackle the inflation caused by the real’s dive. The economy is in recession. Investment in mining and in offshore oil has collapsed.

The currencies of other commodity-intensive countries nearby, such as Argentina and Mexico, have also fallen heavily against the dollar. Among emerging-market currencies only the Russian rouble—slammed by the collapse in oil prices and by sanctions related to Ukraine—has fared worse than Latin America’s miners. Malaysia and Indonesia, the two commodity exporters closest to China, have also been caught up in the sell-off.

After two years of persistent selling, such currencies have begun to look cheap when set against conventional benchmarks. But that has not stopped them falling further in recent weeks as concerns about China’s economy have intensified. The Colombian peso, the Malaysian ringgit and the rouble have been among the hardest-hit currencies in the past week.

The unenviable third bucket

Despite being a commodity exporter, South Africa largely missed out on the China-led raw-materials boom, because of weaknesses in its transport and power industries (see article). It belongs more readily with Turkey in a separate category of emerging markets that have suffered badly because of an over-reliance on hot money to finance a large current-account deficit. Both economies are inflation-prone and have low domestic savings. They also share a tendency to do well when global capital flows freely and to do badly when, as now, investors are choosier about where they park their money.

Ironically, some of the most resilient countries have been those with the closest trade links to China, such as South Korea, Singapore and Taiwan. All have solid current-account surpluses and healthy foreign-exchange reserves and so have little to fear from capital flight in response to rising interest rates in America. And as net importers of raw materials, they benefit from falling commodity prices.

Even so, their currencies fell in the wake of China’s devaluation in mid-August and cracks have recently started to show in their economies. GDP growth in Singapore has dropped below 2%, the lowest rate for three years. Surveys of purchasing managers point to falling manufacturing output in Taiwan and South Korea.

Factory-gate prices are falling across Asia, too, reflecting excess capacity in industry. In China they have declined for 41 consecutive months; in South Korea and Taiwan for 35 months; and in Singapore for 31 months, notes Chetan Ahya of Morgan Stanley. Falling prices make it harder for companies to service the debts they run up to pay for new capacity in the boom years.

Producer prices are falling even in inflation-prone India, which is one of the relative bright spots in emerging markets. India is less tied to China than other economies in Asia and, as a net oil importer, benefits from low crude prices (caused, mostly, by abundant supply in Saudi Arabia and America rather than Chinese wobbles). Its junior finance minister even speaks of taking up the baton of fast growth from China. The worry is that such boasts reveal complacency about reforms that are needed in India but have nevertheless stalled.

With large chunks of the emerging world in trouble, parallels are being drawn with the Asian crisis of 1997-98. Yet many of the factors that contributed to the intensity of that debacle—and the brutality of the recession in emerging Asia that followed—are missing today. The chief absentee is exchange-rate pegs, which were common in the mid-1990s. The illusion of currency stability that such pegs fostered led to a build up of dollar-denominated debts in emerging Asia. When capital inflows dried up, the pegs broke. Currencies quickly plunged in value, pushing up the cost of dollar debts.

These days far more emerging markets allow their currencies to float. By contrast with what happened in 1997, the recent flood of capital from the rich world into emerging markets went largely into local-currency bonds. Foreigners own between 25% and 50% of the stock of government bonds in Brazil, Turkey, South Africa, Indonesia, Malaysia and Mexico, according to Morgan Stanley. For a while the momentum behind capital flows meant rich-world investors enjoyed a virtuous circle of higher bond prices and stronger currencies. Now that cycle has turned vicious but it is the currency (and thus the lender, not the borrower) that has adjusted most. Emerging markets typically have far larger arsenals of foreign-exchange reserves—and healthier current-account balances—than they did in the 1990s.

For these reasons the latest emerging-market dust-up lacks the severity of the 1997-98 crisis. But in at least one regard it is more worrying. The weight of emerging markets in global GDP is now much heavier, mostly because of China’s greater mass (see chart 4). Slower growth there is felt more keenly in rich countries. Worryingly, world trade suffered its biggest fall since 2009 in the first half of this year.

There is one other contrast with the late 1990s. More recently the search for yield in exotic places took rich-world pension funds to the farthest edge of the investing universe: “frontier” markets, which are typically poorer and have less developed financial systems than most emerging markets. Resource-rich Africa was one of the busiest parts of the frontier. Countries that had not long ago been freed from punitive debt burdens were suddenly able to borrow cheaply, albeit in dollars. Sixteen countries in sub-Saharan Africa have now issued such foreign-currency bonds, says Stuart Culverhouse of Exotix, a broker. With commodity revenues falling, repayment could get tricky. Firms that borrowed in dollars could face similar troubles—including some in China that have done so through opaque offshore arrangements.

Quite when the turmoil associated with the end of easy money comes to pass largely depends on the Fed. Before the tumult, markets priced the chance of a September rate rise at over 50%; now the probability is closer to 25%. Grandees such as Larry Summers, a former treasury secretary, and Bill Dudley, head of the New York Fed, have expressed scepticism about a rate rise next month.

Yet the Fed may plough on regardless. America’s economy is well insulated from the Chinese shock: just 8% of American exports, worth 0.7% of GDP, go to China. When discussing the timing of interest-rate rises, Janet Yellen, the Fed’s chairman, usually focuses on the domestic labour market rather than the fate of distant economies. If a jobs report on September 4th shows strong employment growth, the Fed could well raise rates despite market volatility.

After the “taper tantrum” of 2013, a “rate-rise rumble” was always a possibility as the prospect of Fed action neared. That has affected all emerging markets—including China. The crash in Shanghai was not evidence of a Chinese economy on the brink. Nevertheless, policymakers in Beijing have chosen a bad time to lose so much of their credibility as the world economy’s safest hands.