This is the twelfth posting of a reproduction of a series of historical notes, articles,tracts and academic discourses to mark proud landmarks in the history of Somaliland from 1884 which highlight events leading to the country’s two independences of 1960 & 1991.

The Tribute to Captain Allan Gibb, killed in Burao on 24 February 1922 is written by Roland A Hill, MBE. Captain was the District Commissioner of Burao governing most of what we now know as Somaliland’s eastern regions.

—————————————————————–

I was recently browsing in a local bookshop when I picked up a book of short stories called Tales from the Outposts which had been originally published in Blackwood’s Magazine.

In a story called The People without a Pillow written by “Zeres” I recognised the hero named Ian Ross as none other than Mr Allan Gibb, DCM, as he then was, in his capacity as an Assistant District Officer stationed at Zeila on the north coast of British Somaliland in 1911. This clue and the word ‘dead 1922’ alongside his name on the medal roll for his clasp for Somaliland 1920, coupled with information that there had been a civil disturbance in Somaliland in 1922, indicated that, despite a complete absence of service records on this man, there had to be a good story, and the PRO records on the Somaliland Protectorate provided the missing links.

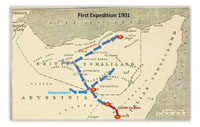

This remarkable man joined Colonel Swayne’s first expedition against the Mad Mullah in 1901 at the age of 23 as an armourer sergeant only to be murdered 21 years later by hostile tribesmen when he was District Commissioner, Burao.

His group of four medals which surfaced recently is of considerable historical importance. The DSO and DCM, linked to the Africa General Service medal with all six clasps to British Somaliland (1901-20), and the War Medal (1914-20) for active service against the Mad Mullah for which no clasps to the  AGS were awarded, represent 20 years of continuous active service in both a military and a civilian capacity. Gibb was the only European, and one of only two, who was awarded all six clasps, the other being Risaldar-Major Farah al Somal.

AGS were awarded, represent 20 years of continuous active service in both a military and a civilian capacity. Gibb was the only European, and one of only two, who was awarded all six clasps, the other being Risaldar-Major Farah al Somal.

Allan Gibb was born on 28 December 1877, the son of a butler, in the parish of Corstorphine in Edinburgh. He was apprenticed to a firm of gunmakers in Frederick Street and joined the Volunteers around 1898. In 1900 he decided to make his career in the army, and he duly enlisted in the Army Ordnance Corps. Skilled armourers were much in demand and he was soon earmarked for overseas service in Ashanti. Due to an accident his posting was cancelled and instead he arrived a year later in Somaliland in April 1901 as a Sergeant armourer instructor.

He subsequently took part in the engagements at Erigo in 1902, when he was mentioned in despatches for repairing a Maxim under hot fire, and again for his bravery at Daratolleh in 1903. He was also mentioned in the official history of the operations in Somaliland for his role at Jidballi in 1904.

|

| Sergeant Gibb at Daratolleh |

Of the action at Daratolleh, Lt Colonel R E Drake-Brockman wrote in an appreciation of his life in The Times, ‘His gallantry on all occasions, but particularly during the rearguard action in which Colonel John Gough and two other officers received the Victoria Cross, earned for him in his humble capacity of a non-commissioned officer the DCM, but I have heard on good authority that no-one on that day earned the coveted VC more than Allan Gibb’. In an obituary notice in The Scotsman it stated that he had been recommended for the highest military honour and in yet another reference to his feat of arms on that day there is a snippet written by the then Governor of Somaliland in 1911 on an internal memo prior to his secondment to the Camel Corps, which reads ‘In view of Gibb’s excellent military record, he saved a British force all by coolly sticking to his Maxim …’, and in another memo ‘we are pledged to Gibb’.

|

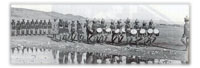

| 6 KAR in Somaliland |

The next mention of Gibb is that he proceeded on leave to the UK in 1905 as a Sergeant-Major. The medal roll for his fourth clasp to his AGS medal for Somaliland 1908-10 lists him as a Lieut Quartermaster with 6th Bn. (Somaliland) KAR when he would have been about 30. When 6 KAR was disbanded Gibb was in a sense time-expired and redundant, having served for nearly 10 years with a colonial force. However, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, the Rt Hon Lewis Harcourt, approved Gibb’s appointment as an Assistant District Officer, despite the fact that all government agencies had been withdrawn from the interior, but more significantly to retain his valuable services in Somaliland. When in 1912 it was decided to form the Camel Constabulary under Richard Corfield, Gibb was asked to be his second-in command. When Gibb was on leave in 1913, Corfield and the Constabulary had a confrontation with the Mad Mullah’s followers at Magala Yer and Corfield and many of the Constabulary were killed.

|

| Camel Corps |

It was then decided to form a Camel Corps under military command for the purpose of re-establishing the Government’s authority in the interior. There was little active service in the Empire at that time and competition was keen for secondment to Somaliland by both British and Indian Army officers. Gibb, now a District Officer, remained as a civilian still on secondment and was appointed a civilian company commander, which in any circumstances must have been an unusual appointment.

Gibb was involved in both actions at Shimber Berris in 1914 and in 1915. He was mentioned in Colonel Cubitt’s despatch and in the Governor’s despatch forwarded to the Colonial Office – ‘From beginning to end there was no hitch of any sort and it is due to the capable handling of the CO and his staff and the excellent leading by the Company Commanders responsible, Capt Breading, Mr Gibb and Lt Eales, that the casualty list was kept so low as it was.’ At this point it was decided to make Gibb a local Captain in the Camel Corps, and thus rectify his somewhat anomalous position as a civilian company commander. His appointment on 20 August 1915 was backdated to 16 September 1914.

He continued to serve in the Camel Corps on secondment from the administration, as did other regular army officers who were refused permission to serve in other theatres of war; until 1918 when he was duly reabsorbed but now with the rank of District Commissioner and stationed at Burao in the interior. At the same time he was informed that his entire service in Somaliland would count towards his civil pension, a rather unusual gesture from a normally penny-pinching Colonial Office, but it highlighted the appreciation of the authorities for his outstanding services. When the time came to launch the final offensive against the Mad Mullah in 1920 Gibb was given command of the tribal levy comprising some 1500 persons, which was to work in close liaison with the Camel Corps. Once again Gibb distinguished himself and although the Mullah just eluded him, he captured his headquarters at Taleh and played his part in the complete rout of the Mullah’s forces. For his services he received one of the three DSO’s awarded for this campaign and this in distinguished company.

|

| Taleh |

He returned to his civilian duties in 1920 and in the following year led a delegation of distinguished Somalis to Aden to be presented to the Prince of Wales, who was en route to India for his Indian tour. Towards the end of December 1921 he settled compensation claims with representatives of a Royal Italian Commission as a result of intertribal fighting on the Anglo-Italian border. Only a few weeks later, on 24 February 1922, he was murdered by tribesmen at the Burao Station headquarters as the direct result of wild protests made against Government proposals to institute a levy to assist in the cost of opening schools, since none existed at that time due to the nomadic existence of these tribes. His death had far reaching effects. The Governor’s despatches covered every aspect surrounding his death, for the Governor had been taking tea with Gibb in his bungalow at Burao a quarter or an hour before his death in company with Risaldar-Major Farah al Somal. The Governor had lent his car to Gibb to enable him to take appropriate action. Unfortunately, although warned by a Corporal of the Somali Camel Corps, in mufti, not to go ahead, he unwisely albeit gallantly went alone to confront the frenzied mob. This time it was a reaction aimed specifically at the Government which Gibb represented. Gibb must have realised too late that this was not the time for heroics and one rifle shot put paid to his life. The Government authorities reacted and RAF planes from Aden flew over the area a few days later.

Gibb’s body was taken to Sheikh where he now lies buried. On 5 March 1922 the Governor called in the tribe concerned with the killing and imposed a fine of 3000 camels for Gibb’s death (tribal custom and law allows for the payment of 100 camels for murder). He also informed them that the Burao station, except for the mosque, would be bombed and burnt by the RAF. This drastic action and the unprecedented fine well illustrated the importance given to the law and order aspect but in part represented the reaction of the authorities to the death of Gibb.

On 14 March 1922, replying to a question in the House of Commons, Mr Winston Churchill, as Secretary of State for the Colonies, gave a detailed account of the action which was being taken and mentioned Gibb by name as an officer of long and valued service to Somaliland whose loss he deeply regretted. Hansard

|

| Somaliland Medals |

There is only one known photograph of Gibb (though no doubt others exist) and a sketch of him behind his Maxim at Daratolleh. It was acknowledged ‘that no British officer has ever had such a wonderful insight into the Somali character nor presented so sound a colloquial knowledge of the Somali language’. Gibb who was a bachelor had been completely dedicated to his work with the Somalis and in his continuous travelling in the interior, under sometimes appalling conditions, he must have faced danger and hardships too numerous to mention.

And now a further word to this brief account of Allan Gibb and it goes back to the action of Daratolleh in 1903. From a detailed study of this action, a list of all officers present, and the reading of the citations for the Victoria Crosses and what was not recorded by the untimely death of Maude, the Argus correspondent, there is the strong supposition that but for Gibb, working under terrible conditions and in that thorn bush country, there would have been not only no survivors from the rearguard but few survivors, if any, from the main body. What Gibb had prevented was a repetition of the action at Gumburu in early 1903, when a force composed of 231 officers and other ranks of the 2nd Bn. (Nyasaland) KAR in similar circumstances were virtually wiped out save for a handful of survivors.

Both Drake-Brockman, a doctor of many years’ service in Somaliland, and the Acting Commissioner in 1911, acknowledge that Gibb did something very special on that day and he can be considered extremely unlucky not to have received the Victoria Cross in company with the three officers so honoured.

Postscript

What Gibb effectively accomplished in the rearguard action at Daratolleh was to physically move his maxim alternatively from the left face to the right face whilst being attacked from both sides. “Geeb” as he was known by the Somals was buried at Sheikh and not at Burao for security reasons. I have a coloured photograph of his unmarked gravestone which lies under the shade of a tree near the edge of a dry river bed with goats and donkeys grazing nearby. Gibb is also remembered in both poem and film as is Richard Corfield, the more widely known District Officer, buried with his servants in unmarked graves at Magalla Yer. Unfortunately the continued unrest and the lack of diplomatic representation in Somalia since 1991 have made tying up loose ends virtually impossible.

by Roland A Hill, MBE

Source: Britishempire.co.uk