FOR most of human history, pregnancy has come with a significant risk of death. Up until the early 1930s in America, nearly one woman died of related complications for every 100 live births. Thanks to advances in obstetric medicine and widened access to better care, the maternal-mortality rate declined by almost 99% over subsequent decades—one of the great public-health achievements of the 20th century. By 1987, fewer than eight women died for every 100,000 live births. Over the past quarter of a century, however, America’s maternal-mortality rate has been creeping back up (see chart).

By 2013 the rate had ticked up to 18.5 women for every 100,000 births (these numbers include women who die within 42 days of childbirth). This makes America an international outlier. Between 2003 and 2013 it was one of only eight countries, including Afghanistan and South Sudan, to see its maternal-death rate move in the wrong direction. American women are now more than three times as likely to die from pregnancy-related complications as their counterparts in Britain, the Czech Republic, Germany or Japan.

What is going on? Some suggest that the country is simply getting better at counting maternal deaths. In 1999 America adopted a new cause-of-death coding system, and in 2003 states began including a pregnancy check-box on death certificates. But this does not explain why the rate has more than doubled over the past quarter-century and continues to go up, says William Callaghan of the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which collects maternal-mortality data. There may even be some undercounting, as states categorise deaths differently.

One theory is that the rise reflects the changing age profile on the maternity ward. More women are getting pregnant later in life, which makes childbirth riskier. Women who were 35 or older made up fewer than 15% of live births between 2006 and 2010, but accounted for more than 27% of pregnancy-related deaths, according to the CDC. Yet similar trends can be seen in other parts of the world, such as Western Europe, where mortality rates have continued to fall.

Others point to the fact that nearly a third of all American births now involve a Caesarean section, up from nearly 21% in 1996. Any surgery increases the risks of complications and multiple C-sections make these problems worse. (Women who undergo C-sections are often encouraged by doctors to use the procedure for subsequent births.) “Most of us think the C-section rates can be reduced,” says Michael Lu, who oversees maternal and child health at the federal Health Resources and Services Administration.

But the most compelling explanation is that more American women are in poorer health when they become pregnant, and are failing to get proper care. Chronic health conditions, such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes and heart disease, are increasingly common among pregnant women, and they make delivery more dangerous. Indeed the traditional causes of pregnancy-related deaths, such as haemorrhage, thromboembolism and hypertensive disorders, have been declining in recent years, whereas fatalities from cardiovascular conditions and other chronic problems have been on the rise.

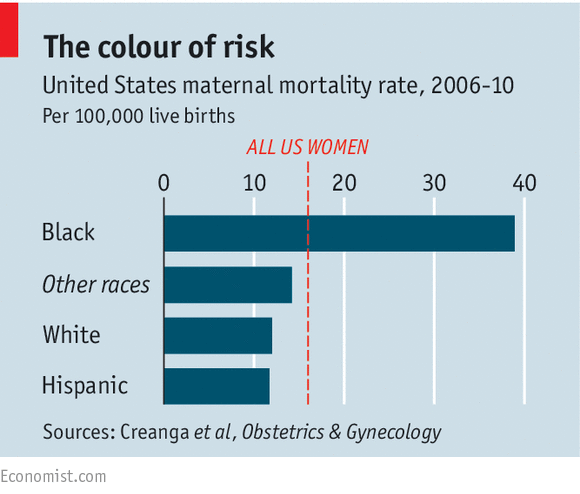

These health conditions are more common among black women, 40% of whom qualify as obese, compared with 22% of whites. African-Americans are also more likely to be poor, have limited access to health care and have higher rates of unexpected pregnancies: this may explain why they are nearly four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications than white women, almost double the discrepancy that existed 100 years ago.

Though such deaths are still rare, they are only the tip of the iceberg, says Dr Lu. For every woman who dies, he estimates there are roughly 75 who experience a near-fatal emergency during pregnancy or childbirth such as heart attacks, kidney failure or profuse bleeding. These obstetric crises have also increased in recent years.

Golden State copiers

There is nothing inevitable about the rise in maternal mortality: California, where one out of eight American births take place, has reversed it. In 2007 a study of the state’s maternal deaths found that more than 40% were avoidable. In response, state agencies, hospitals, doctors and midwives came up with new ways to manage obstetric haemorrhage and pre-eclampsia, the two leading preventable causes of maternal death. California introduced these plans in 2010, and the state’s maternal-mortality rate has since plummeted to just over six deaths per 100,000 pregnancies, from nearly 17 in 2006.

Inspired by California’s success, federal, state and professional organisations including the CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, have got together and introduced plans for handling obstetric haemorrhage, severe hypertension (extremely high blood pressure) and venous thromboembolism, the three most treatable causes of maternal death. The aim is to have procedures in place everywhere babies are born around the country within three years, and to halve maternal deaths within five years.

But while getting hospitals to adopt new emergency protocols is a proven way to reduce maternal deaths, there is still the matter of women who are entering pregnancy in poor health. Medicaid already pays for almost half of all births in America, but millions of new mothers lost coverage 60 days after delivery, with the result that many entered their next pregnancy in bad shape. Some hope that the expansion of Medicaid in 29 states under the Affordable Care Act will result in healthier mothers-to-be. There are also plenty of charities trying to help. A non-profit group in Philadelphia called the Maternity Care Coalition recently launched a scheme which pairs at-risk pregnant women with health workers until six months after childbirth. This project is one of several around the country, part of a larger ten-year, $500m investment in reducing maternal mortality around the world from Merck, a pharmaceutical company. “We expected to be doing all our work in developing countries,” notes Priya Agrawal of Merck.

Source: The Economist