More than one million people died in East Africa during World War One. Some soldiers were forced to fight members of their own families on the battlefield because of the way borders were drawn up by European colonial powers, writes Oswald Masebo.

I was born and raised in a simple home in the rural district of Ileje about 1,000km from Dar es Salaam, in south-west Tanzania. The district is at the border with Malawi where the hilly plateaus of Ileje and Rungwe districts rise above the plains of Lake Nyasa and Kyela district.

My family has made a living from the land of Ileje for generations. During World War One, Ileje and the surrounding environments became a battle ground between German forces and British allied forces from Malawi.

Although the war began in 1914, it was the battles fought in 1915 and 1916 which were most intense and which had grave consequences to the generation of my great-grandparents.

Ten years ago, I asked my own grandfather Jotam Masebo what he knew about World War One. His recollections remind us of grinding hardship. I quote:

“Our parents narrated to us a lot about this war. The timing of the war was bad. It broke at the time when our parents were about to begin planting maize, beans, cassava, groundnut, and potatoes… The fighting created fear and insecurity that disrupted the agricultural production of our parents and led to the most acute famine that killed many people. The fighting killed innocent men, women, and children.”

The fighting at the river Songwe border was particularly notorious because some of the soldiers and carrier corps involved in it were related to enemy soldiers.

People living on both sides of the border lived together as a single community until the notorious Berlin Conference created a boundary to separate the German colony of Tanzania and the British colony of Malawi. The boundaries passed through the middle of these people and divided them. They would come to fight during World War One, representing the interests of their respective colonial masters.

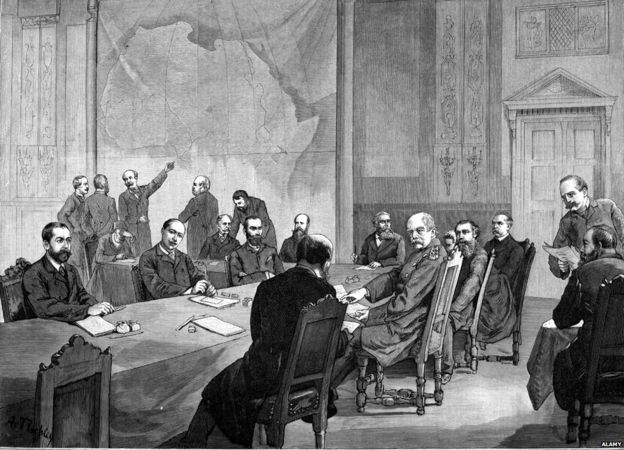

The Berlin Conference

- The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 was convened by Otto von Bismarck to discuss the future of Africa

- The Berlin Act of 1885, signed by the 13 European powers in attendance, included a resolution to “help in suppressing slavery”

- The colonial powers were more interested in protecting old markets and exploiting new ones though, and they began carving up Africa leaving people from the same tribe on different sides of European-imposed borders.

On a recent visit back home and I asked the elders what they know of World War One.

An old man known as Ngubhombeleghe Swilla advised me to go to Ngana and hills to witness look-out posts and machine-gun mounts that still exist today.

I set out to see them – a day’s journey. The leader of Kasumulu village walked with me to a high vantage point on the outskirts of the village where metal structures, now rust into the hillside. I was astonished to find these remnants of World War One heritage in my region.

It was from here in 1916 that German forces fled to Mozambique.

Although Tanzania was a battleground for World War One, very little is known about the role, position and social identities of Tanzanians who directly participated in the war.

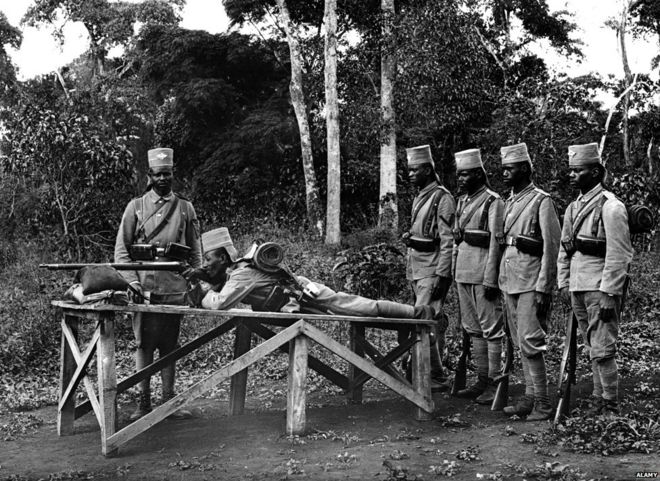

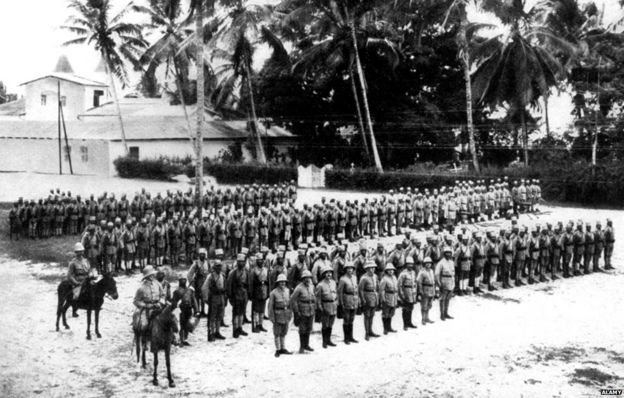

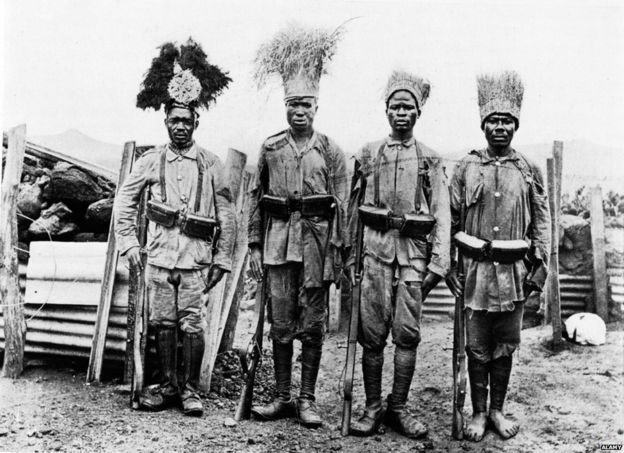

Existing scholarly narratives focus on German and British military personnel. Yet, oral sources I have collected claim that African men and women played a key role in sustaining the war-related operations in south-west Tanzania. Kaswashi Pwele of Kapelekesi and Labani Kibona of Isoko – who I interviewed in 2008 – recounted that Africans were a majority in the German colonial army. They emphasised that the German colonial army was essentially an African army. But they could not tell the exact number of Africans in the army. John Iliffe’s archival research suggests that Germany had about 15,000 soldiers in south-west Tanzania in 1916 out of whom about 3,000 were Germans and the remaining 12,000 were Tanzanians whose names are not recorded.

John Iliffe’s archival research suggests that Germany had about 15,000 soldiers in south-west Tanzania in 1916 out of whom about 3,000 were Germans and the remaining 12,000 were Tanzanians whose names are not recorded.

The Tanzanian carrier corps also played a central role in sustaining the war. Their story should be recovered.

It is estimated that during the peak of military operations in 1916 the German colonial state conscripted some 45,000 African members of carrier corps.

And let’s not forget the general public of ordinary men and women who grew food such as maize, beans, and cassava. They also raised cattle, goat, sheep, pigs, and chicken. The colonial armies relied on this food to feed soldiers and carrier corps. Oral recollections tell us Tanzanians did not give out this food willingly. Armies acquired it by force, by looting Tanzanian rural homes and communities. In 1996, Kileke Mwakibinga recalled:

“At the time of the war, of 1914, I was still a young boy. But I was watching the entire goings on when the soldiers were passing… elders were persecuted and persecuted. Others were captured here and there. I was watching all this… They came and looked for things… they would enter a house, if they found milk they would just take it. If they saw chicken, they just took them. That is when the Germans were fleeing.”

Find out more Oswald Masebo is Professor of History at the University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Oswald Masebo is Professor of History at the University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Dar es Salaam – Ubhuche, Invisible Histories of the First World War broadcasts on BBC Radio 3’s The Essay: World War One Round the World on Friday 3 July at 22:45. It is part of a global year-long partnership between the British Council, BBC World Service and BBC Radio 3 called The War That Changed the World. You can catch up via iPlayer.

Both the German military forces in Tanzania and the invading British forces from Nyasaland and Rhodesia engaged in these barbaric acts of looting food reserves of the generation of my great-grandparents, creating a food shortage which my grandfather spoke about.

But perhaps the most surprising element in this elusive story is a silence of the names and identities of African soldiers and carriers in the oral history itself.

I find this to be surprising and unique because Tanzanian soldiers and leaders who participated in other military engagements are known and remembered.

For example, some of the names and identities of Tanzanians who fought in the Maji Maji wars of resistance in Southern Tanzania from 1905 to 1907 are known and remembered.

Maji Maji wars were local protests against German colonial exploitation, oppression, and forced cultivation of cotton. The resistance was sparked by a charismatic spiritual leader Kinjekitile Ngwale who claimed to possess medicine which would protect warriors against German bullets, turning them to “maji”. Maji is the Kiswahili word for water. Many people died as bullets never changed into water.

Maji Maji remains a heroic story in Tanzania, which is taught to every young Tanzanian in primary and secondary school. Kinjekitile Ngwale is celebrated and romanticised for his readiness to die in order to preserve the independence, autonomy, and respect of Africans. The Maji Maji museum in Songea was built to celebrate the heroic lives of soldiers and leaders of the war – it contains narratives, sculptures, and even pictures of these heroes. Each year there is a month-long commemoration of the annual Maji Maji war in that district.

An Askari monument in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

So why is the story so different for World War One? Why are the names and identities of thousands of Tanzanians who served as soldiers and carrier corps unknown?

Perhaps this is because they were not appreciated by Germany.

In some oral accounts Germany even held them responsible for Germany not winning the war. Kaswashi Pwele claimed that “German military officials blamed Africans for not winning the war. They accused some Africans for lacking loyalty to Germany and for leaking security information to Britain.”

But isn’t the key reason for the invisibility of the names and identities of Tanzanian soldiers and carrier corps to be found in the attitude of the British colonial state which took over from the Germans?

Elders told me the British were very suspicious of Africans who had worked for the Germans. Soldiers and carrier corps who served in the German army were the least trusted.

According to the elders, some of these soldiers and carrier corps were deported to Nyasaland. Some were detained for some years.

It was risky to be labelled a pro-German royalist. It was dangerous.

As a coping strategy, many men who had participated in the war on the German side made “creative adaptations” by concealing their identities and war experience.

“Creative adaptations” – it’s another way to say “hiding the truth”, perhaps a polite expression for lying. I have translated creative adaptations from the word ubhuche, in the Ndali language, my mother tongue and the language used by elders I spoke to.

Ubhuche helped people to avoid the dangers of a new colonial regime. This helped them to live peacefully and to prosper under British colonialism. They also learned to speak negatively about German colonialism, even those who had individually benefited from it.

The silences on the names and identities we see today are probably the result of this creative adaptation of African soldiers and carrier corps to the British colonial regime after the war.

It might be too late to interview the eye witnesses but listening closely, creatively, and critically to our elders, we can still hear echoes of the voices of African soldiers, carrier corps, and the larger public during World War One. Let me conclude by reflecting on that visit I made to the south west. I’m going to make Ubhuche – a Creative Adaptation of my own – I’m going to adapt what I’ve learnt from research to imagine the invisible stories of World War One.

Let me conclude by reflecting on that visit I made to the south west. I’m going to make Ubhuche – a Creative Adaptation of my own – I’m going to adapt what I’ve learnt from research to imagine the invisible stories of World War One.

Standing in the World War One battlefields at Kasumulu, I could see the River Songwe that the British and German colonisers used to divide our great-grandparents as different people: as either Tanzanians or Malawians.

I also saw a glimpse of a soldier from a century past, standing with his rifle. Next to him, a carrier with supplies for the colonial army on his head and back. I imagine them as proud men of values. They accepted the war, probably reluctantly, and went to fight against British Malawian soldiers, perhaps their cousins who lived on the other side of the River Songwe.

They have no military uniform. They fought in traditional dress. I know some killed enemies, and some of them died. And when I think of them, I don’t think only of the conflict they fought in, but also the inner conflict that they combated at the end of the war.

It’s important for me to remember the public too, the impact on my great-grandmother and her children during the war. I imagine the ordinary men, women, and children in those hills, plains, and along the river.

They were full of fear and insecurity, they suffered from acute food shortage, had their houses burned by combatants, they were exhausted by war traumas.

Women and children were probably at the highest risk from this global crisis that unfolded in their villages.

But I know that just as my people suffered in this war, many also survived and overcame the challenges. Their creative adaptations, the Ubhuche, helped them to endure and prosper.

They may be invisible in the mainstream history.

Let us not forget them.