This is the third of a series of notes, tracts and academic discourses to mark proud landmarks in the history of Somaliland from 1884 to highlight events leading to and evolving around the country’s two independences of 1960 & 1991.

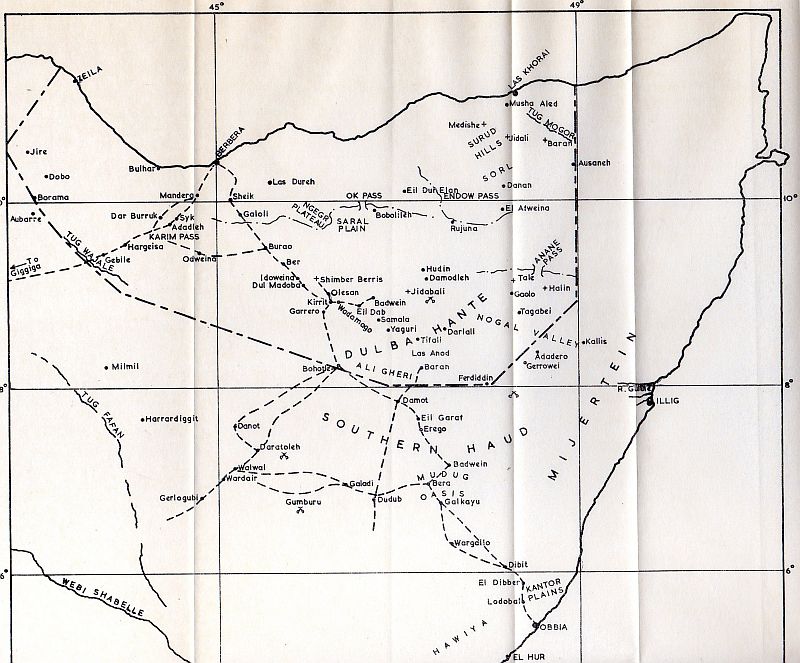

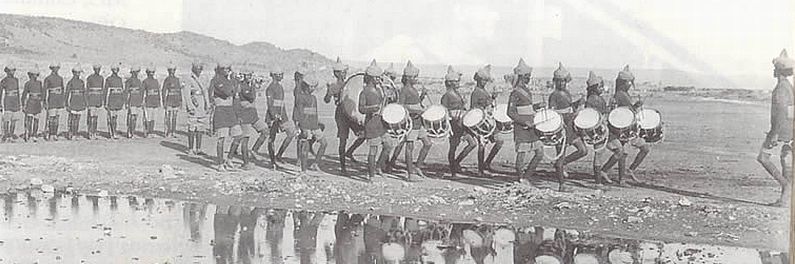

By March of 1905 the Mullah was in treaty agreement with the Italian authorities and had accepted the requirement to live a peaceful life with his followers in the vicinity of Illig. The British had covertly supported Italian ambitions elsewhere in Somaliland by influencing the Zanzibari Sultan to concede the Benadir ports, and by recognising an Italian land claim near Kismayu. The Somaliland Protectorate was now under new direction from London as in 1905 the Colonial Office took over responsibility from the Foreign Office. The Mullah did keep to his side of the bargain for a couple of years until the grazing areas around Illig became exhausted and insufficient for his followers’ herds and flocks.Meanwhile the British reorganised their defence force in the Somaliland Protectorate. After some deliberation and changes 6th King’s African Rifles (6 KAR), the Somali-based battalion, was organised in 1906 as a unit of six rifle companies. A local Somali Standing Militia, formed after the Fourth Campaign, had been disbanded after the bulk of its personnel were transferred into 6 KAR. Four of the new rifle companies contained Somalis whilst the other two were composed of seconded Indian Army volunteers. Of the four Somali companies ‘A’ and ‘B’ were pony-mounted, ‘C’ was mule-mounted and ‘D’ was a Camel Company.

One of the Indian companies was stationed in cantonments near the small Sheikh blockhouse, and the other in a mud fort at Burao. The fort at Bohotle had been dismantled and those at Shimber Berris and Kirrit were unoccupied; the strong blockhouse at Las Dureh was garrisoned by a few tribal riflemen. The Somali rifle companies occupied garrison posts along the caravan routes. Thus the Protectorate troops were dissipated on outpost duty in locations that probably would not withstand a serious Dervish attack, and there was no military reserve to put into the field if such an attack was launched. In October 1907 the British Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, 33 year-old Winston S. Churchill, made a brief stop in Berbera and travelled inland to see the country. He was not enthusiastic about what he saw, and recommended either a withdrawal to the coast or an occupation of the interior that, in an alliance with the Italians, would crush the Mullah. He deplored the lack of a submarine communications cable between Berbera and Aden, which would be a small investment that could be used to quickly request reinforcements. Back in London nobody was particularly interested in Churchill’s report, and it gathered dust whilst its author moved on to become President of the Board of Trade. But the Mullah was not without his critics within Islam. In 1908 he was denounced from Mecca by the head of the Salihiya Tariqa, Sheikh Salih, as a sinner against Allah and the Prophet, a veritable kaffir, an unbeliever and a madman. Although this denunciation was widely circulated in the Protectorate the British failed to use it to advantage by obtaining the Turkish Grand Mufti’s comments on the matter, and the Mullah finally shrugged it off, brutally dealing with opponents who publicly mentioned it.

By early 1908 complaints were pouring into Berbera from the interior stating that agitators were again proclaiming the right of the Mullah to be the leader of all the Somali inland tribes. The last thing that the British wanted was the expense of another campaign but something had to be done, and a decision was made to send around 1,200 KAR Askari from other Protectorates into the Somaliland interior to uphold British prestige and rule, whilst 300 Indian Sepoys arrived from Aden. First to arrive in January 1909 was Battalion Headquarters and 300 Askari of 1 KAR from Nyasaland, under Lieutenant Colonel H.A. Walker (Royal Fusiliers). The battalion marched up to Wadamago where it performed mundane escort duties and fatigues for a year before returning to Nyasaland. In February 1909 Battalion Headquarters and 450 Askari of 3 KAR, under Lieutenant Colonel J.D. McKay (Middlesex Regiment), arrived from Kenya and also performed security duties in the Wadamago region for a year. Finally Lieutenant Colonel B.R. Graham (Corps of Guides, Indian Army), brought his 4 KAR Battalion Headquarters and 460 Askari for their 12-month stint in the Somaliland interior, returning to Uganda in February 1910. Despite not firing a shot in anger, all those troops who had served in Somaliland or off its coastline between August 1908 and January 1910 became eligible for the clasp SOMALILAND 1908-10 to the African General Service Medal. Whilst the KAR Askari were marching thirstily up and down the dusty camel trails in the interior without gaining sight of an aggressive Dervish, Lieutenant General Sir Reginald Wingate, Governor General and Sirdar of the Sudan, had been attempting without success to negotiate with the Mullah. Wingate’s partner in this mission was General Sir Rudolf (Baron) von Slatin, Inspector General of the Sudan. The British administration had become adamant that it would not finance another campaign, and when Wingate’s & Slatin’s negotiations failed the decision was made to abandon the interior of the Protectorate. Italy protested, as this withdrawal meant an end to the treaty with the Mullah, but Britain was determined to withdraw into what was termed the Coastal Concentration.

Coastal Concentration

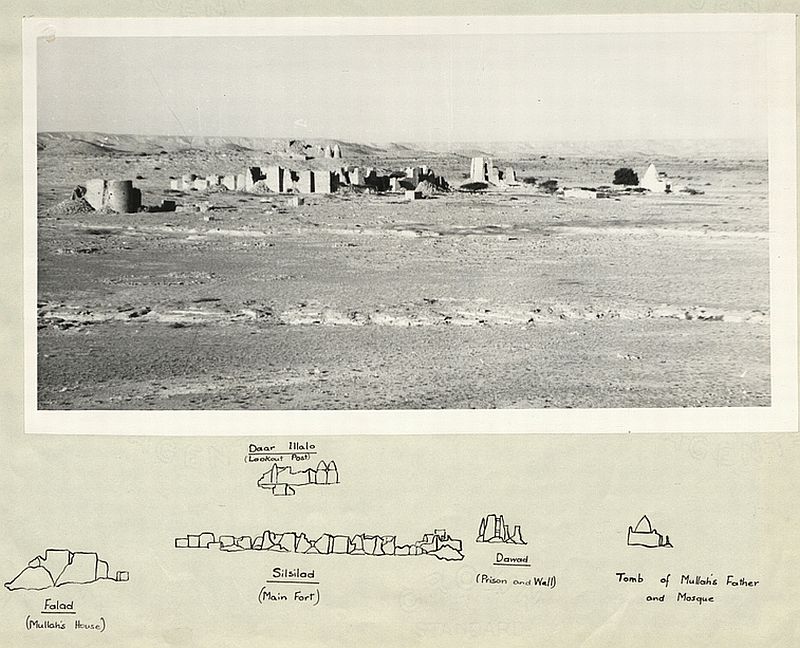

The Mullah observed this British military activity and thought it a preliminary to another campaign against himself and his followers. He started one of his periodic bouts of flowery letter-writing with Byatt, expressing a desire for peace. Byatt’s answer was to the point – the Mullah could prove his intentions by ending raids and ceasing exhortations to tribes ostensibly still under British protection to join the Dervishes in a jihad or holy war. The Mullah’s correspondence ceased in 1912 as he entered into a period of building permanent stone forts at Laba Bari, Bohotle, Damer and Taleh – a magnificent fort that was his pride and joy. Professional stone masons and fort-builders were recruited from Yemen to supervise the construction. It is probable that at this stage in his life the Mullah was becoming more obese and immobile as a result of elephantiasis; his days as a swift-moving nomadic warrior were now just memories.

The battle of Dul Madoba

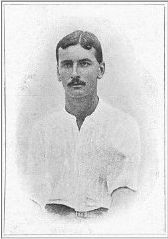

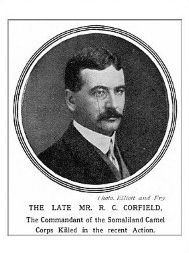

In January 1913 the Corps occupied Sheikh and then Burao, but was not permitted to advance further south although it did move west to settle disputes at Hargeisa. But Corfield chafed at the bit and did move south to Idaweina to search for Dervish raiders. This action resulted in a critical memorandum to Corfield written by the Acting Commissioner Geoffrey Francis Archer, who reminded Corfield that the Corps was to stay near Burao and was not to take offensive action. Eight months later Archer visited Burao accompanied by Captain G.H. Summers, 26th (King George’s Own) Light Cavalry, Indian Army, who commanded the Indian Contingent in Somaliland. Archer’s arrival was quickly followed by reports of Dervishes attacking friendly tribes between Idoweina, Burao and Ber. The friendly tribes requested British protection, and in order to discover the facts Archer authorised Corfield to make a strong reconnaissance towards Ber; Summers was ordered to accompany Corfield as the military advisor. On 8th August a 15-man pony section from the Constabulary was order to reconnoitre, and shortly afterwards Archer permitted Corfield with 119 camel-mounted men to follow up the reconnaissance and observe the situation. The riflemen carried .303 Martini Henry rifles with 140 rounds in bandoliers plus a reserve of 60 rounds in their saddle bags. Also one Maxim gun with 4,000 rounds of ammunition packed in cork-lined tin boxes was transported on camels. At 1900 hours that evening one of the pony reconnaissance party was met coming back to report. He stated that a large force of Dervishes was driving many herds of looted stock towards Idoweina; the reconnaissance party had engaged the enemy, firing over 80 rounds each, and had hit several Dervishes who in retaliation had killed two ponies. Corfield advanced for a couple of hours and then formed a zariba with the camels sat down in the centre. The fires in the Dervish camp could be seen about eight kilometres distant. The pony section returned with a Dervish strength estimate of 2,000 footmen and 150 mounted men, all armed with rifles. The Dervish leader was Ow Yusuf Abdillah Hassan, a brother of the Mullah. Local friendly Dolbahanta tribesmen assured Corfield that they would provide at least 300 men tomorrow, armed with rifles or spears, to assist in recovering their stolen stock.

Corfield moved his men out at dawn, tracking the Dervish line of march by the dust clouds that the herds threw up. At 0645 hours near a location named Dul Mahoba (black hill) Corfield’s men were ordered into a skirmish line to face the left flank of the Dervish advance, with the Dolbahanta tribesmen positioned on the left flank. Corfield attempted to advance his line through thick bush in order to reach more open ground ahead but the Dervish advance was too swift, catching Corfield in a totally unsound position where his men could not always see each other. Summers urged Corfield to form a square, the safest formation to adopt as it could not be dangerously out-flanked as a line could, but Corfield wanted all his riflemen to fire at the same time, and so he left them floundering in a skirmish line without a reserve of troops or flank or rear protection. The Dervishes scented victory and charged forward, firing as they ran; nearly all the Dolbahanta tribesmen immediately fled the scene. The Constabulary line was quickly outflanked causing some of Corfield’s men to disperse to the rear. The Maxim gun fired three belts but was then permanently put out of action by bullet strikes on the mechanism. Richard Corfield, who had positioned himself near the gun, was shot and died instantly at about 0715 hours. Summers, who was hit three times and badly wounded, and Dunn rallied their surviving men and formed a protective zareba from the bodies of the dead camels and ponies that now littered the battlefield. The wounded were brought into the zareba and a very few Somali officers and senior ranks began to exert fire discipline over the surviving riflemen. Dervish attacks, which consisted of forward rushes that sometimes delivered warriors into the zareba, continued until 1100 hours when they began to tail away, and an hour later the Dervishes withdrew altogether with their captured herds as their stocks of ammunition were exhausted. The Dolbahanta who had initially fled the scene now returned to loot the bodies on the battlefield. Dunn, now the force commander, sent a report to Archer and cleared the battlefield whilst a reconnaissance patrol followed the Dervish movements. Twenty six riflemen remained fit to fight, and 16 wounded needed evacuation on the surviving camels. In his after-action report Summers praised Colour Sergeants Gaboba Ali and Jama Hersi and Sergeant Jama Said for the leadership and gallantry that they displayed during the battle. He also commented on the extreme bravery of the Dervishes, and on their use of modern rifles that had been obtained from traders working out of Djibouti and Muscat.

At around 1500 hours that afternoon, when the reconnaissance patrol had established that the Dervishes were not lying in wait, Dunn withdrew to Idoweina where foul but just-drinkable water was found, and then moved slowly through the night to meet up with Archer at Gombur Magag, 30 kilometres from Burao which was itself reached on the morning of 10th August. As well as the death of Corfield and the wounding of Summers, 32 riflemen were killed and 15 wounded in the zareba. A further 31 riflemen had gone missing from the zareba but most re-joined the column the next day. The losses in mounts were 50 camels and 9 ponies; the Dervishes had seized four of these camels, the remainder being either killed in the battle or wounded and put down later. The number of Dervish dead was estimated at between 200 and 600; many Dervish wounded later died of their wounds. As the Mullah had ordered the ponies to be tied up away from the battlefield all the Dervish mounts survived. Awards made for the action were Captain Gerald H. Summers appointed to be a Brevet Major and Captain Cecil de S. Dunn to receive the Police Medal. During 1913 Geoffrey Archer was appointed a Companion of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George (CMG). Withdrawal from Burao

_______________________________________________________________________________________ (An edited version of this article has appeared in an edition of the Journal of the Anglo-Somali Societyhttp://www.anglosomalisociety.org.uk/Home.php ) SOURCES: · Moyse-Bartlett, H., The King’s African Rifles. 1956, Gale & Polden Ltd, Aldershot. Reprinted by The Naval & Military Press Ltd.

|

||||||||||

The 1908-1910 ‘Campaign’

The 1908-1910 ‘Campaign’

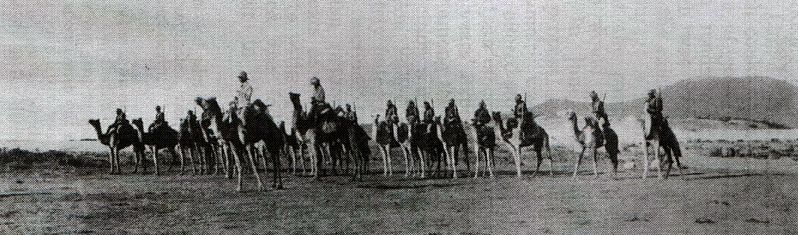

Left: Corfield distributing arms in Burao Fort.

Left: Corfield distributing arms in Burao Fort. Corfield expressed his intention of either attacking the Dervish camp that night or of intercepting the enemy during the next day, and he sought Summers’ opinion. Summers was adamant that Corfield could not win a battle against such a strong Dervish force, and he urged him to stick to his orders and just reconnoitre. But Corfield wanted a battle and he decided to intercept the Dervishes the next day.

Corfield expressed his intention of either attacking the Dervish camp that night or of intercepting the enemy during the next day, and he sought Summers’ opinion. Summers was adamant that Corfield could not win a battle against such a strong Dervish force, and he urged him to stick to his orders and just reconnoitre. But Corfield wanted a battle and he decided to intercept the Dervishes the next day.