She was, by almost all accounts, a rather wonderful woman – smart, helpful, and engaging – and a familiar presence behind the old-fashioned wooden reception counter in the Central Hotel’s spacious lobby in the Somali capital, Mogadishu. “We made a really good connection. She was very attentive, and was doing her job very well. One government minister I knew was ready to offer her a job,” said a European official who sometimes stayed at the hotel in order to meet the many Somali politicians who had made it their home. He asked for his name not to be used for security reasons.

“We made a really good connection. She was very attentive, and was doing her job very well. One government minister I knew was ready to offer her a job,” said a European official who sometimes stayed at the hotel in order to meet the many Somali politicians who had made it their home. He asked for his name not to be used for security reasons.

“She was a nice person, really talented,” confirmed the hotel manager and co-owner, Ahmed Ismail Hussein, of Luul Dahir, the Somali woman in her mid-30s whom he had hired four months earlier.

‘She exploded here’

“She had six young children, and everyone was sympathetic and supportive. But after all, to me she was not a nice person. She was a horrible person when you consider what she did,” he said.

On 20 February, a car bomb was driven inside the hotel’s heavily guarded courtyard during Friday prayers.

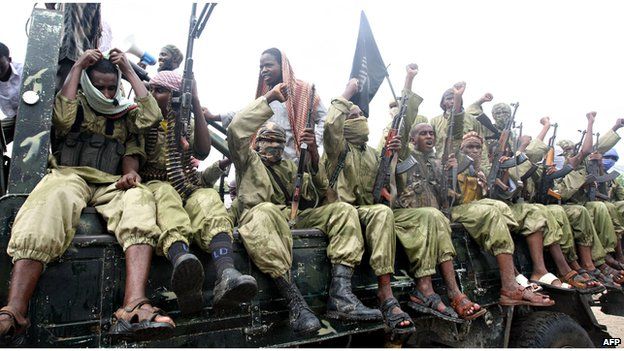

Car bombs have become a common sight in the streets of Mogadishu

Dozens of men, including ministers and a deputy prime minister, were praying in the hotel mosque.

Somehow, the mosque wall managed to absorb most of the blast, and for minutes afterwards, dazed survivors wandered around the courtyard.

This was the moment Luul Dahir chose to make her move.

The manager had noticed earlier that morning that she seemed tired, and tearful – and had asked her if she wanted to take a day or two off.

“She was looking down – I told her: ‘Please, take leave.’ She was not willing to go,” he said.

Underneath her black chador she had strapped a belt packed with explosives.

“She exploded here, this black spot. She was looking for the deputy prime minister, asking: ‘Where is my uncle?’ He was not really her uncle but she wanted to make sure he dies,” said Mr Hussein, showing me around the scarred courtyard.

Others remember hearing her scream – trying, they thought subsequently, to attract a crowd around her.

Mr Hussein suspects there might have been a scuffle – that the minister’s bodyguards even fired shots at Ms Dahir.

But she managed to detonate her bomb.

“I believe not less than 40 people were killed here”, said Mr Hussein. Official figures suggest about half that number.

‘Shortcut to paradise’

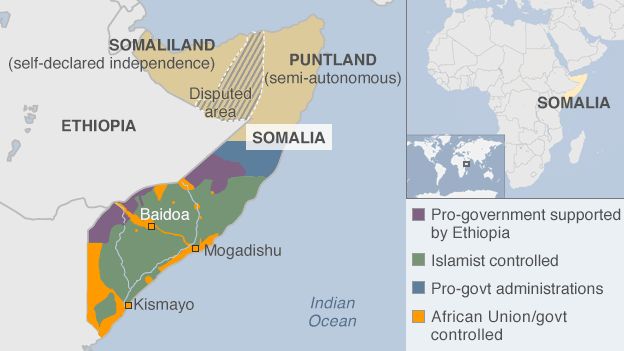

The al-Qaeda-linked Somali militant group, al-Shabab claimed responsibility for the attack. More details about Luul Dahir soon emerged.

She had recently returned from Holland, where she had lived since childhood as a member of Somalia’s huge diaspora.

She had applied for jobs at a number of prominent hotels in Mogadishu. In her letter to the Jazzier Palace hotel, she had described herself as:

“A dynamic professional who strives for excellence in all assigned tasks. I have good customer service skills. I consistently approach work with energy. I am a team player.”

Her hobbies included “reading new novels” and “learning new things.” Her application was rejected.

Ms Dahir’s late husband, named as Abdi Salan, had been involved in another al-Shabab suicide attack, one year earlier, on Mogadishu’s heavily guarded government compound, Villa Somalia.

Somehow, none of this had come to light before the attack. Indeed, it is alleged that several senior security officials had befriended Ms Dahir at the hotel.

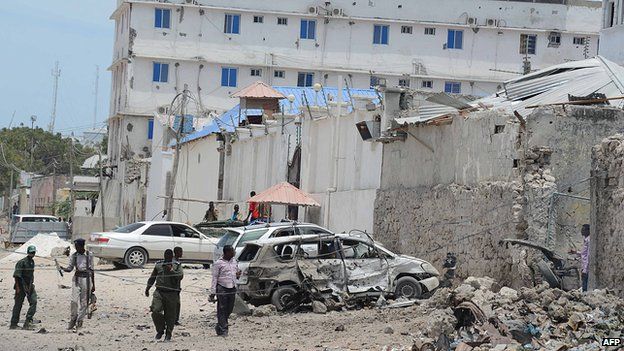

A number of Mogadishu’s popular hotels have been targeted by car bombers in recent years

“I believe these guys, al-Shabab, use weak people – people with difficulties. They tell them this is a short cut to go to paradise,” said Mr Hussein, who had also returned to Somalia recently after 24 years in Sheffield, England.

“Later I learned that [Luul Dahir] had problems with her sight. Her husband was dead. I heard he was another suicide bomber,” he said.

“She had six young children and was struggling… So I think her mentality was turned… she had been told: ‘Paradise is waiting for you. Your husband is waiting for you’,” he added.

The Central Hotel bomb was by no means a one-off. Mogadishu’s political elites have been targeted in a series of recent hotel attacks – several involving members of the diaspora.

“People keep asking: ‘Why do the diaspora come back to kill themselves and kill others?’

“They say we cannot trust the diaspora because they’re blowing themselves up. It’s very hard now to get confidence and trust from others,” said women’s rights campaigner Ifrah Ahmed.

Two days after we visited the Central Hotel, a car bomb exploded on the street outside, killing diners lunching at a popular restaurant.

The manager, Mr Hussein, replayed the explosion for us on the hotel’s CCTV.

“They’ve parked right opposite our door. That young boy… will be among the dead very soon. That’s the one…. You can see the car burning there,” he said quietly, describing the scene unfolding on the screen.

“I’m very pessimistic. It needs a sea of change to happen here. The government is doing absolutely zero. They’re just going… around and around, fighting among themselves,” he said.

Since the second bombing, which broke most of the hotel’s windows – only just replaced after February’s attack – Mr Hussein is actively considering a return to Britain.

“Two years ago property was booming, there was a lot of activity. But since then 80% of the diaspora went back because of the deteriorating security situation,” Mr Hussein told me.

“Only a few like me are still here, and I cannot go back easily because I invested a lot of work and money. But I don’t know how long I can stand on my feet… I may go back to the UK,” he said.

Ms Dahir’s actions continue to haunt him, and many others who encountered her in the days leading up to February’s attack.

The anonymous European official, who had been so struck by her enthusiasm, now remembers a seemingly throwaway comment she made – as they discussed security at the hotel – which has now come to have much more sinister undertones.

“She said – and I think this is word for word – ‘It’s not the number of guards on the outside. It’s who gets inside that will make it unsafe.’ That was on the Wednesday before that attack,” he said.