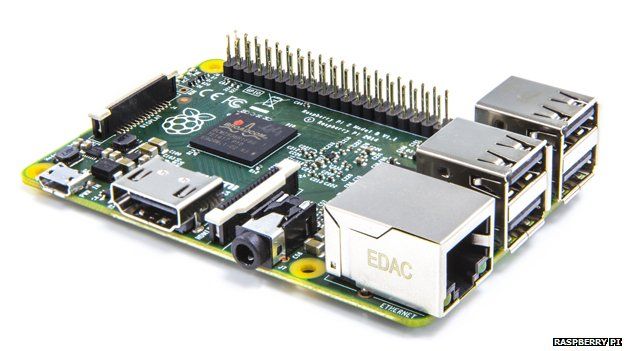

It has been three years since the credit-card sized Raspberry Pi launched.

The Pi, and its community web pages, try to tempt the public and students to burrow beneath the bonnet of their computers, beyond Facebook, and try their hand at coding.

And with five million sold, it is today Britain’s fastest-selling personal computer, a $35 (£25) successor to kit – or unassembled – computers like the Heathkit H8.

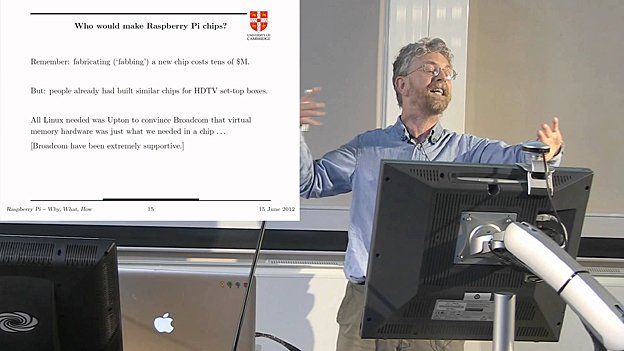

Eben Upton, Alan Mycroft, and four other academics at the University of Cambridge’s Computer Laboratory had noted a decline in skills and numbers of students applying to read Computer Science.

Twenty years before, applicants would have been avid tinkering hobbyists; lately, they may have only done a small amount of web design.

The European Commission has predicted a shortfall of 900,000 adequately skilled programmers and other technology professionals in Europe by 2020.

So the sextet founded the Raspberry Foundation as a charity to revive Britain’s garage-geek spirit.

When British astronaut Tim Peake heads to the International Space Station this November, he will bring two augmented space Raspberries, called Astro Pis.

They will run experiments devised by primary and secondary school students, says Dr Upton, Raspberry’s chief executive. The older students will also code them.

Programming 2.0

Programming is changing briskly.

Coding in the cloud is one trend likely to carry on, spreading collaborators across continents.

So also is the explosion of new languages, like Facebook’s Hack scripting language or Apple’s Swift, alongside classical tongues like C and Java.

We’re likely to learn to code younger, and differently. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) child-friendly programming language Scratch has 6.2 million registered users.

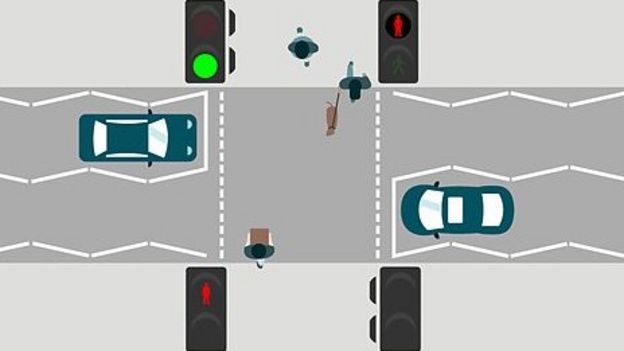

The Internet of Things, driverless cars, and drones will all yield more programmable platforms – but will coding for your cappuccino maker drastically change programming?

And what will the coding workplace be like, when today’s Raspberry rugrats have grown into tomorrow’s programming prodigies?

Drones and other connected devices mean that there’s more demand than ever for IT professionals

One interesting facet of the last 15 years is how little programming languages have changed.

Then and now, C and C++ dominate programming at deep, or highly-optimised levels.

One level up, C-derived languages – objective C and ones resembling C in syntax, like Java and Microsoft’s C# – are in fashion for running most applications.

Then at the top, there is a big brace of scripting languages, like Perl, Python (named after Monty Python), and PHP, which is often used as glue for sticking together programmes to build a complete system.

Scripting languages live in a rich environment, with large numbers of links to other programmes, says Daniel Kroening, professor of computer science at the University of Oxford.

Some, like Haskell in quantitative finance, are dominant in niches because of available frameworks and libraries.

Fortran (first released in 1957, though much evolved since) continues to be used for scientific programming, including weather forecasting and climate-change modelling.

And there is JavaScript, the predominant language for programming to run in a web browser.

School pupils have a go at coding the Astro Pi

Programmed for change

The spread of computing to new platforms – down to your car and toaster – will bring new challenges in building bigger, more connected systems.

Scripting languages tend to be loosely typed, allowing a single variable to contain a number, a bit of text, or other character.

This makes writing small programmes easier, faster, and more fragile.

Agile development has been another new trend, with frequent feedback between programmers and users – the gov.uk website is an example.

But then you have the million-line behemoth programmes, with more opportunities for inconsistencies and bugs to creep in.

BBC iWonder

Another trend has been an increased number of languages coming out of the corporate world, rather than universities. This permits companies to have more control over which direction the languages take.

“Nowadays, by accident, Facebook have a million lines of PHP, and they wish they didn’t,” says Alan Mycroft, professor of computing at Cambridge University.

Facebook as a result has developed a new language, Hack, to help keep types constant through large masses of code.

But it requires very speedy coding.

Nobody said IT was easy.

Google’s Go is in this category, as is Mozilla’s Rust.

Dropbox – largely coded in Python- hired Python’s creator Guido van Rossum three years ago.

We can see Microsoft’s C# as an earlier example of industry-driven design.

Programming languages behave like ecosystems, says Professor Mycroft.

New small languages are constantly developed, then suddenly a large corporation will use one.

“There’s no God-given right to why one language lives and one doesn’t,” he says.

C first became popular because Unix, Linux, and Windows were written in it. Java became popular because it enabled easy animation (applets) on early web pages.

Progress is meanwhile being made in languages particularly suited to machine learning.

These have made great bounds lately in visual recognition, and in solving CAPTCHAs – those irritating jumbles of hidden words you have to type in to a website to prove that you are not a robot.

In this family of languages, the programme, not the programmer, comes up with the algorithms needed to address a problem.

The maths needed for this sort of inference has made great strides in the last three years, says Dr Frank Wood, from Oxford’s Department of Engineering Science and creator of the probabilistic programming language ANGLICAN.

Not so BASIC anymore

Another feature of tomorrow’s programming workplace is that software projects will “only ever become bigger”, says Oxford University’s Professor Kroening.

With the adequately trained talent spread around the world, “remote working will grow more pervasive”, says Sophia Drossopoulou, professor of programming languages at Imperial College London.

She points to her husband’s company, with 70 people distributed over 10 countries.

Prof Sophia Drossopoulou says with talent spread around the world, home working will become common

Crucial to this are laptops that are now powerful enough for useful development.

Asher Glynn, a software architect in London, says he has teams working everywhere from Ukraine to Australia to Portugal.

“The thing that you do miss out is the face-to-face bonding,” he says. “But I think we’ll develop new techniques for dealing with the individual’s feeling of isolation.”

He points to co-working locations. Skype and other forms of teleconferencing will become more important adds Brendan Quinn, a London-based technology consultant.

All this could be yours

Worldwide, the number of people working in programming is in the order of 15 million.

This number is not rising fast enough, even though the number of things to be programmed is.

India produces roughly 100,000 computer science graduates annually. By comparison, Britain produces roughly a tenth of that.

Good news for qualified programmers, less so for tech companies facing talent shortages.

“That’s why we work with organisations like Code Club, Young Rewired State and Raspberry Pi to inspire young people to get involved with coding and digital technology,” says Eileen Noughton, managing director of Google UK.

Dash and Dot are robots that help children to learn how to code

Pushing this even further, Vikas Gupta, an Amazon and Google veteran with a three and a half year-old daughter, co-founded the Wonder Workshop in Silicon Valley in 2012, to teach children to code.

In December 2014, it began shipping two robots – Dash and Dot.

Using music and drawing interfaces, the robots entice young children to develop coding skills, like ordering commands in a sequence, and working in subroutines.

Maybe it is a little too keen to imagine an entire future generation of Raspberry-reared garage programmers. But they are likely to be in short supply.

So perhaps spare a thought for Steve Jobs beginning Apple in his parents’ garage, before you convert yours to a spare bedroom for the au pair or the mother-in-law.

Source: BBC